The Last Mission to Nagasaki Was In Jeopardy Before It Even Got Off the Ground

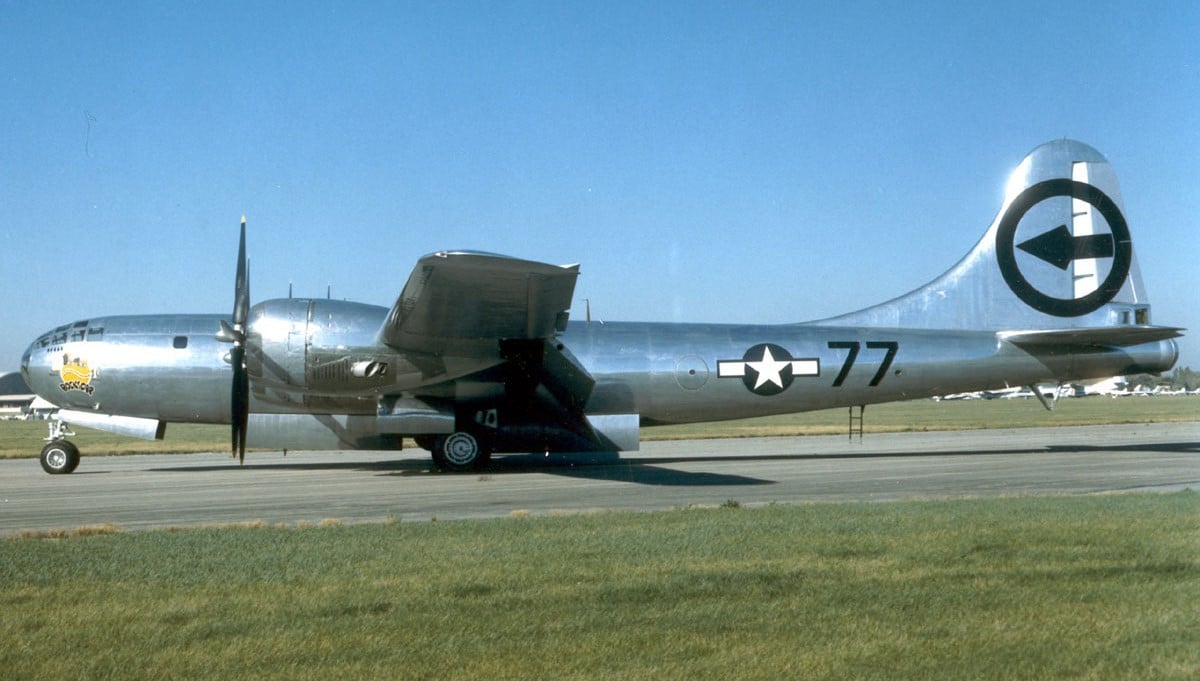

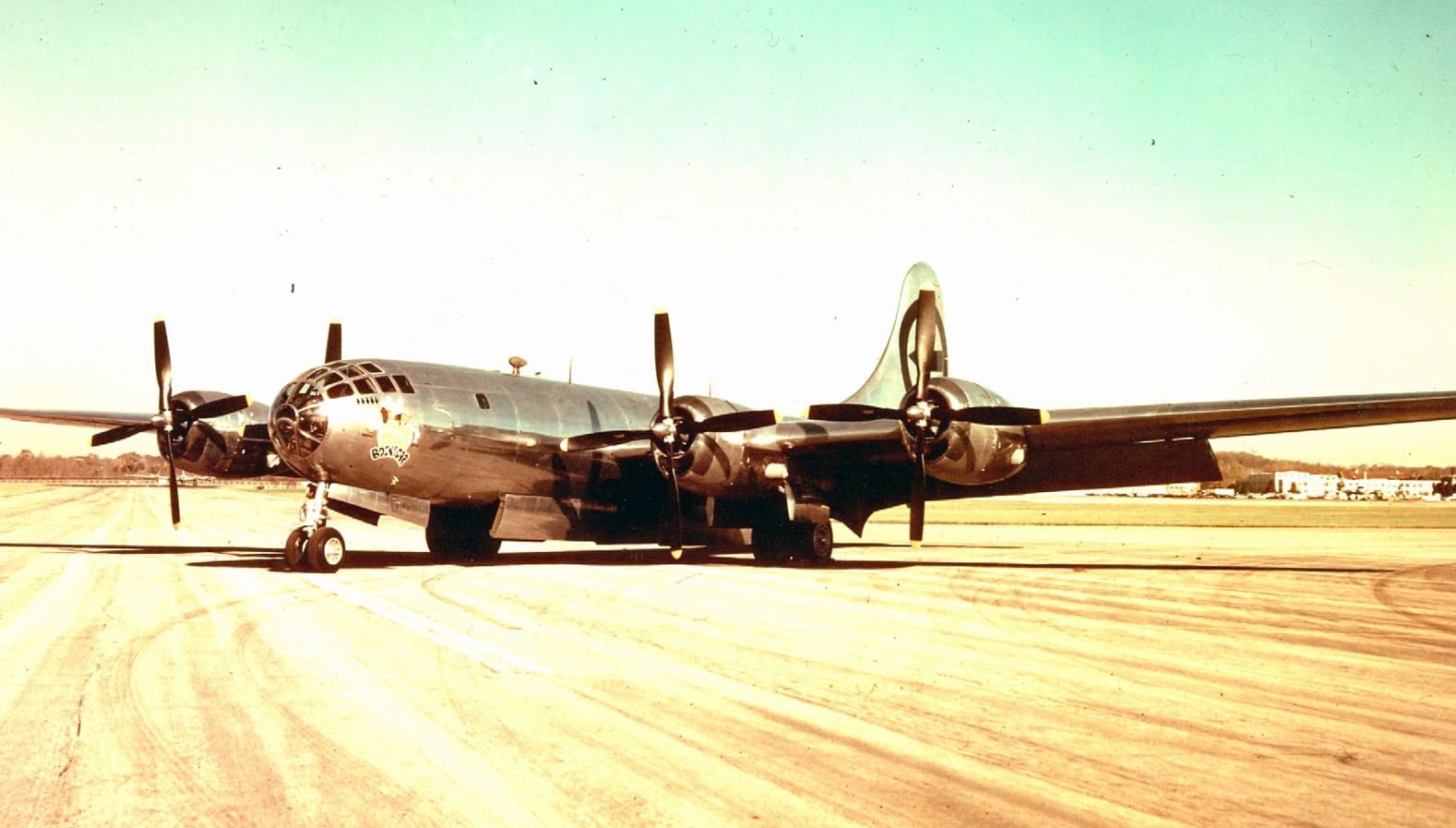

Perhaps the second most famous Boeing B–29 Superfortress bomber ever, B-29-36-MO Air Force serial number 44-27927, nickname Bockscar, flew a mission that up until three days earlier had never been flown. 44-27927 was a specially modified block 35 B-29. The aircraft was built, not by Boeing, but by the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Plant in Bellevue, Nebraska.

Martin built a total of 536 B-29s for the US Army Air Forces (USAAF), the first of them being accepted by the USAAF in mid-1944. 44-27927, modified to Block 36 Silverplate standards, was named Bockscar. Bockscar dropped the second and last wartime atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

Silverplate Specials

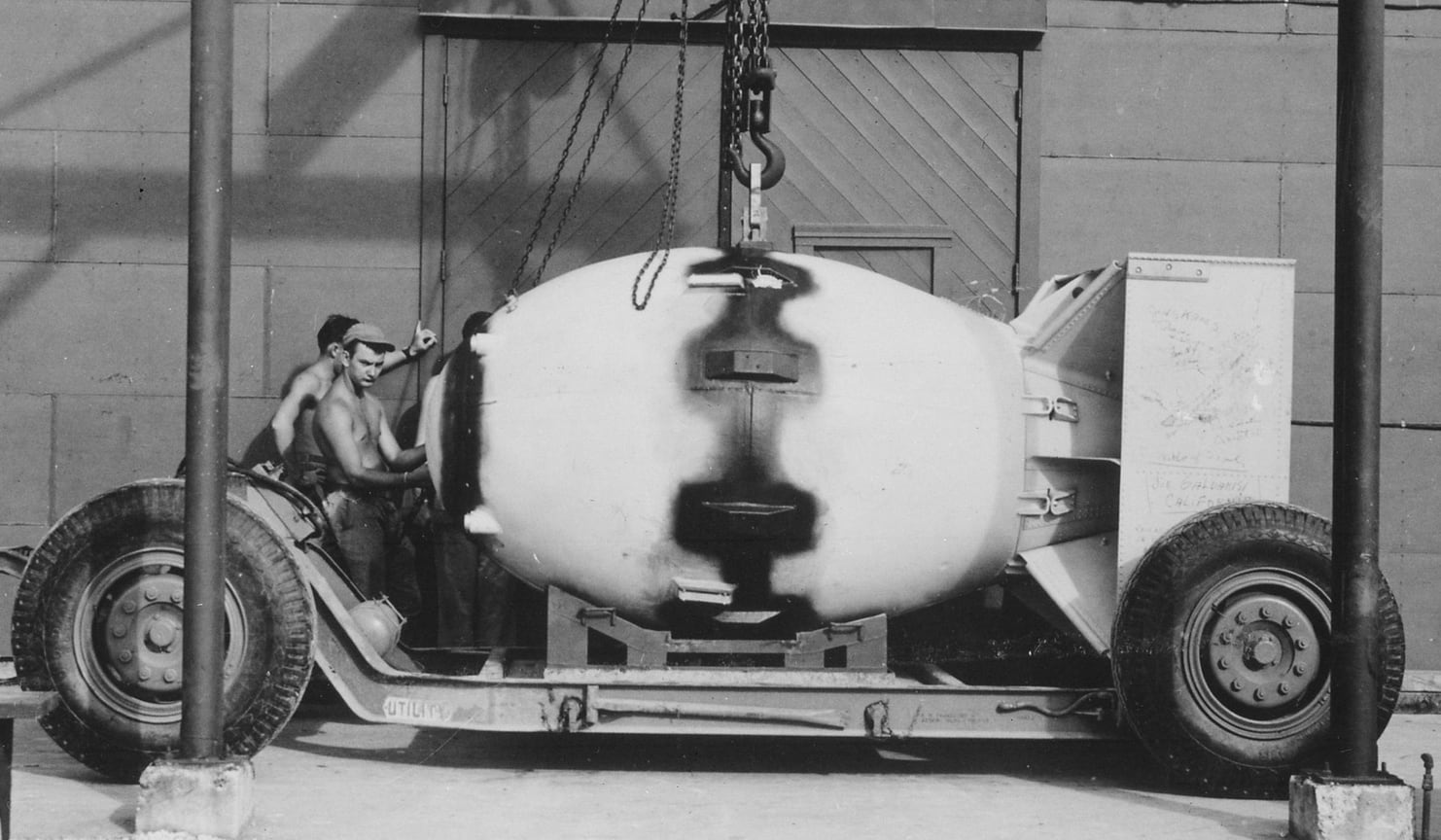

Silverplate B-29s were modified to enable them to carry the atomic bombs of their day. Revisions to these special Superforts included pneumatically operated bomb bay doors, dual redundant British bomb attachment and release systems, improved Wright R-3350-41 Duplex-Cyclone turbo-supercharged radial engines with revised fuel injection and cooling systems turning reversible propellers, and the removal of the dorsal and ventral remote-controlled gun turrets. A weaponeer crew position was added in the cockpit area.

Bockscar Working Her Way West to Tinian

B-29 44-27927 was accepted by the USAAF on 19 March 1945 and assigned to Captain Frederick C. Bock and crew C-13 of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron (BS) of the 509th Composite Group. However, like all 509th bombers the name of the B-29 was not painted on it until after its 9 August mission. Bockscar was flown to Wendover Army Airfield (AAF) in Utah, arriving in April of 1945.

The aircraft was used for crew training at Wendover until 11 June 1945, when it departed for points west. After arrival in the Marianas Islands after stops in California and Hawaii a few days later, Bockscar received final modifications at Guam and arrived at North Field on Tinian, at the time the world’s largest airport, on 16 June.

Spurious Markings to Confuse Enemy Spies

After arrival at North Field, the USAAF painted the bomber to resemble an aircraft assigned to another Bombardment Group (BG) to confuse any potential spies. Once declared operational, Bockscar flew 10 training missions.

The bomber also flew three combat practice missions, dropping 10,000 pound “pumpkin” bombs on the Japanese cities of Niihama, Musashino, and Koromo. As with all 509th Composite Group Silverplate bombers, several different crews flew missions in Bockscar during these practice missions.

The Great Artiste and a Big Stink

Bockscar had been flown by 393rd BS commander Major Charles W. Sweeney on three dress rehearsal practice flights leading up to the 9 August mission. For the 9 August mission, Bockscar was flown again by Sweeny and not by Captain Bock. Bockscar was accompanied by two other Silverplate B-29s: The Great Artiste, normally flown by Sweeney but flown by Bock on 9 August and designated as the observation and instrumentation aircraft that day.

The Great Artiste had already been fitted with the instrumentation equipment for the 6 August mission. Also flying with Bockscar on 9 August was The Big Stink, designated the mission photography aircraft and flown by Major James I. Hopkins. Or at least that was the plan…

5,000 Pounds of Unusable Fuel for Bockscar?

After loading the now-live Fat Man atomic bomb aboard Bockscar, routine pre-flight inspection revealed that an inoperative fuel transfer pump made it impossible to use the 640 gallons of fuel carried in a reserve tank. Replacing the pump was not an option; moving the Fat Man bomb to another aircraft wasn’t either.

The fuel would add two and a half tons of dead weight to the already overloaded bomber. Even with the risks, Group Commander Colonel Paul Tibbets and Sweeney decided to fly the mission in Bockscar.

Improvising, Adapting, and Overcoming

When Bockscar departed runway A North Field at 0349 on 9 August the bomber was bound first for a rendezvous with The Great Artiste and The Big Stink at Yakushima Island. The primary target for the mission was Kokura. The mission’s secondary target was Nagasaki.

The mission was also originally scheduled for 11 August but weather forecasts over Japan were unfavorable so the schedule was moved up. But there they were. Weather reconnaissance bombers Enola Gay and Laggin’ Dragon reported acceptable weather over both primary and secondary targets at that time. Then The Big Stink didn’t show up at the rendezvous.

This Is Why We Have Backup Plans

Mission commander CDR Frederick Ashworth USN urged Sweeney to wait for The Big Stink, thereby burning precious fuel and delaying the mission. After 45 minutes Bockscar and The Great Artiste set course for Kokura without The Big Stink. But Kokura was by then 70% obscured by a combination of cloud cover and smoke from a raid on nearby Yawata the night before.

Bockscar flew three bomb runs with increasing Japanese anti-aircraft fire over Kokura. Concern about the flak over Kokoura and activity on the radio frequencies used by Japanese fighter directors pushed Bockscar to the secondary target: Nagasaki.

By Twist of Fate Nagasaki Becomes the Target

The weather over Nagasaki wasn’t much better but it was free of flak and threats from Japanese fighters. Fuel was becoming a critical consideration too. The decision was made to bomb the secondary target using radar but at the last minute a hole in the clouds opened up.

Bombardier Captain Kermit Beahan dropped the Mark III Fat Man bomb visually at 1058 local time. It exploded 43 seconds later approximately a mile and a half northwest of the aiming point.

That 5,000 Pounds of Unusable Fuel Again

Thanks to the delays at the rendezvous and the three bomb runs at Kokura, Bockscar was unable to make it back to North Field or even to usual alternate Iwo Jima. The aircraft landed at Yontan Airfield on Okinawa on fumes with one engine out from fuel starvation and lost a second engine on the runway.

Even using reverse pitch on the two running engines, the aircraft nearly came to grief at the end of the runway but a last-second 90 degree turn kept Bockscar from the overrun. Remaining fuel was calculated to be less than 5 minutes-worth.

Confusion and Mixed-Up Nose Art

Some confusion ensued after the mission due to the spurious markings on the bombers and the lack of nose art. Bockscar was flown back to Tinian but flew no more combat missions. The bomber flew back to the States and took up residence at Roswell AAF with the remaining 393rd BS and 509th Composite Group B-29s.

Not selected for use during Operation Crossroads, Bockscar was instead transferred to the 4105th Army Air Force Unit at Davis-Monthan AAF for storage in August of 1946. For some reason at Davis-Monthan, Bockscar was displayed, but wearing the nose art from The Great Artiste. After a month, 44-27927 was removed from Air Force inventory and transferred to the US Air Force Museum.

Bockscar Beautifully Restored and Honored at the USAFM

Bockscar remained in storage, but with the correct nose art applied, at Davis Monthan until 26 September 1961, when the bomber was flown to Wright Patterson Air Force Base (AFB) in Dayton.

As displayed today at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Bockscar wears the proper nose art applied after the 9 August 1945 mission to Nagasaki. Bockscar is often referred to as the aircraft that ended World War II.

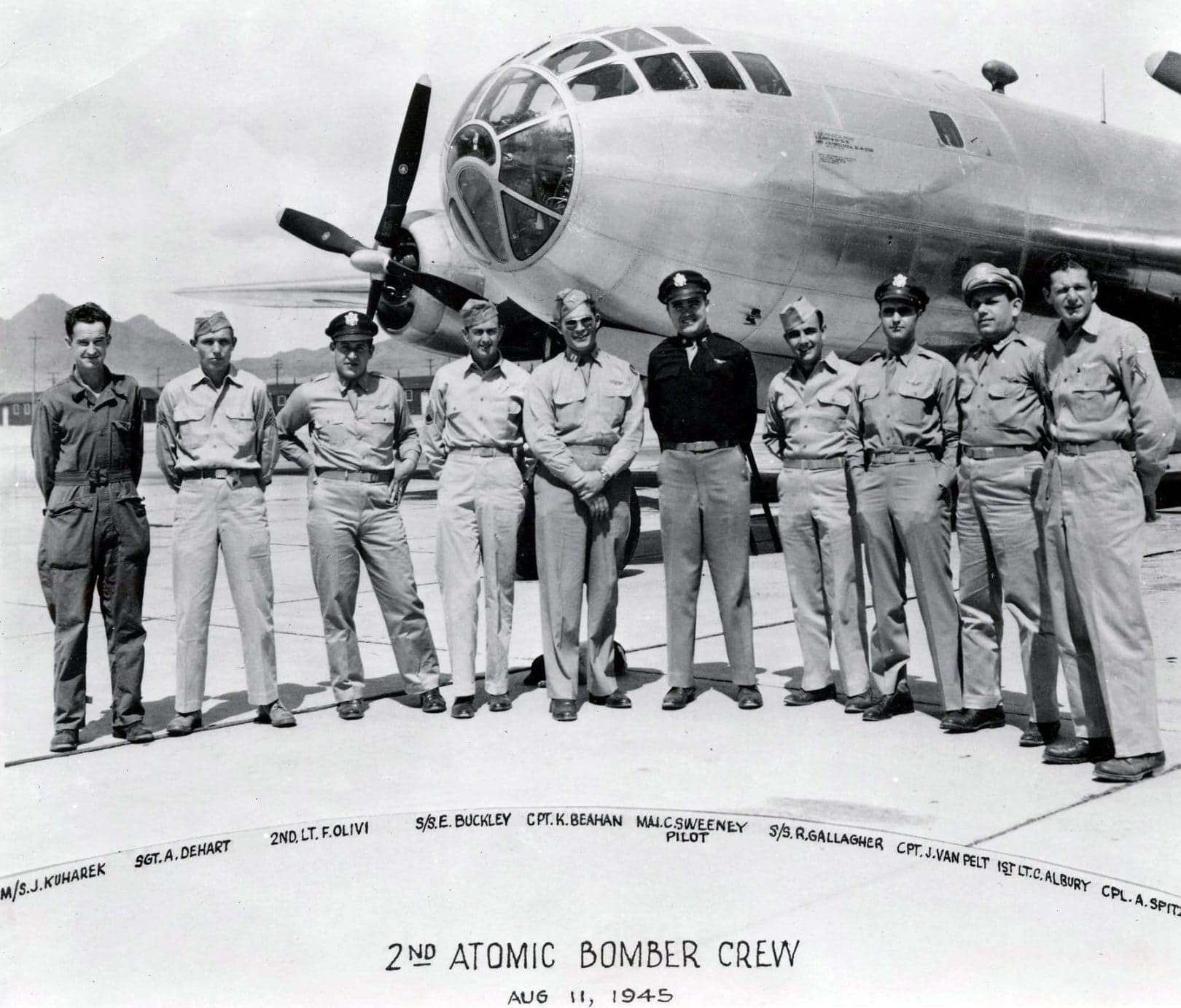

The Bockscar Crew on That Fateful August Mission in 1945

On 9 August 1945, Bockscar’s crew was pilot Major Sharles W. Sweeney, co-pilot Captain Charles Donald Albury, regular crew co-pilot Second Lieutenant Frederick J. Olivi, Weaponeer and Mission Commander CDR Frederick Ashworth USN, Assistant Weaponeer LT Philip M. Barnes, USN, Navigator Captain James F. Van Pelt, Jr., Bombardier Captain Kermit K. Beahan, Radar Countermeasures officer Second Lieutenant Jacob Beser, Flight Engineer Master Sergeant John D. Kuharek, Assistant Flight Engineer Staff Sergeant Raymond C. Gallagher, Radar Operator Staff Sergeant Edward K. Buckley, Radio Operator Sergeant Abe M. Spitzer, and Tail Gunner Sergeant Albert T. DeHart. Beser was the only crew member to fly on both Enola Gay and Bockscar during their respective atomic bomb missions.