The Groundbreaking Douglas DC-5 Machine That Suffered From Bad Luck and Worse Timing

This is the story of the DC-5, the least popular Douglas aircraft ever built. In 1938, most companies in the United States were still trying to claw their way out of the Great Depression, but the Douglas Aircraft Company was flying high. Two years prior, the first Douglas DC-3 had entered commercial service, and the type became an immediate hit.

Douglas was turning out winners

Often described as the first airliner that could make money flying just passengers, without the additional revenue generated by transporting air mail and cargo, the order book for DC-3s was being filled by requests from airlines the world over. More than 10,000 examples would be produced – in both civilian and military variants – before production ceased in 1946.

The DC-3 was an outgrowth of the DC-1 and DC-2. The single DC-1 built served as a prototype for the improved production-line model, the 14-passenger DC-2. The DC-2 design was then enlarged and improved into an airliner that could transport 21 passengers in state-of-the-art comfort. That aircraft was the DC-3.

While dozens of DC-3s were being assembled at the manufacturer’s Santa Monica, California, facility, Douglas designers and engineers were busy creating the next models to join the DC (Douglas Commercial) line of aircraft.

The company’s 1938 Annual Report gave an update on the progress of the single DC-4 that had been built, which had made its first successful flight on June 7 of that year. This aircraft, which boasted four engines, a triple-tail, and a pressurized cabin, would be designated the DC-4E (Experimental) and did not resemble the single-tail, unpressurized production model DC-4 (and military variant, the C-54), which would eventually occupy the Santa Monica assembly line.

Like the DC-3, the DC-4 was a very successful design and hundreds of DC-4s and C-54s would be built during the early 1940s.

A NEW HIGH-WINGED DC-5 EMERGES

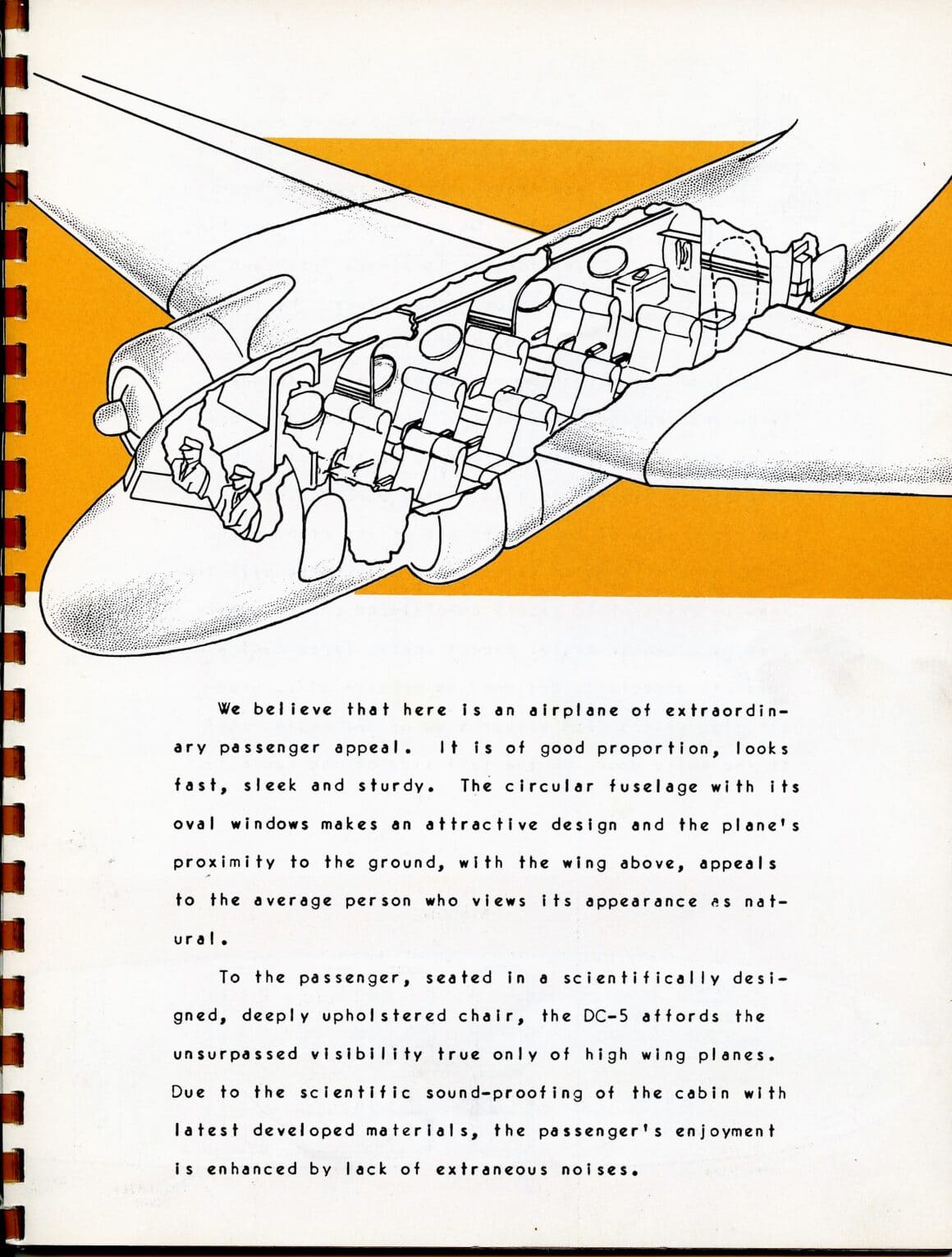

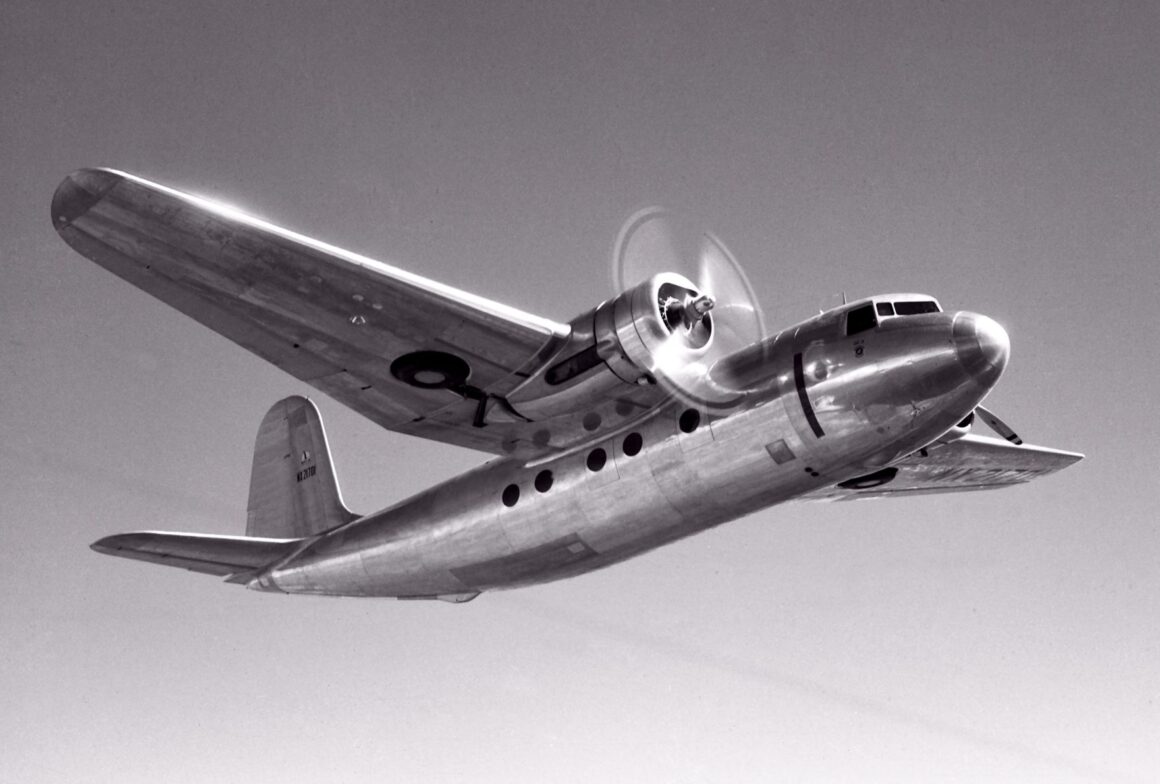

Also in the 1938 publication was a description of the next type in line, the DC-5. The Douglas Annual Report described it as a high-performance, high-wing, twin-engine monoplane capable of operation from smaller airports. The prototype was test flown in February 1939, and it demonstrated excellent performance.

Though the DC-5 was designed to carry 16 passengers in three compartments, capacity could be adjusted to accommodate 14, 18, or 22 seats.

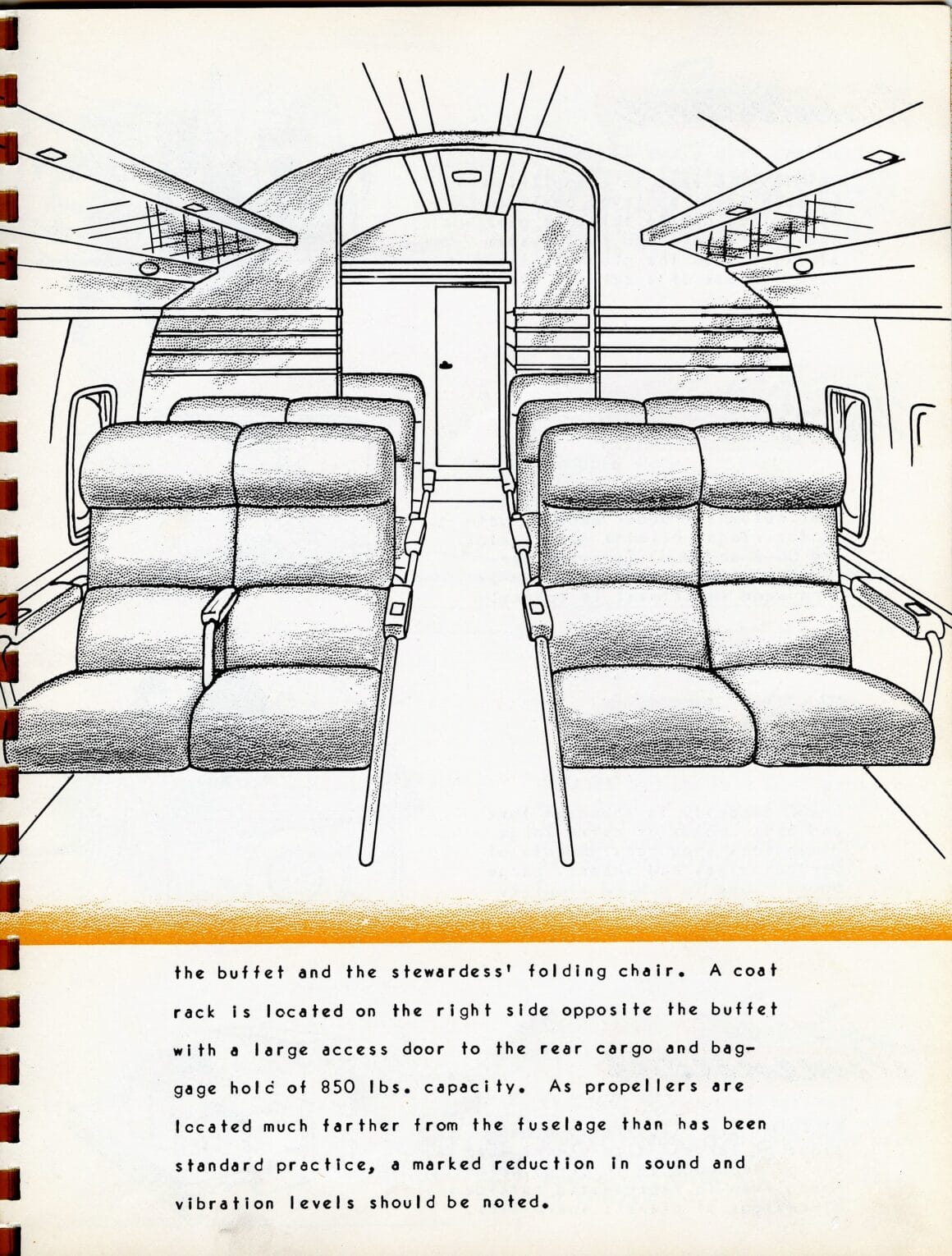

A Douglas Aircraft sales booklet explained that, because the wing was above the fuselage, “large oval windows are especially designed to provide wide, unobstructed vision from either side of the cabin [and] as propellers are located much farther from the fuselage than has been standard practice, a marked reduction in sound and vibration levels should be noted.”

DC-5 Had Unique Capabilities

The DC-5 offered short-airfield capability. It could take off in less than 1,000 feet with 16 passengers and a crew of four aboard – 1,500 feet if a 50-foot-high obstacle had to be cleared – no matter which set of approved Wright or Pratt & Whitney engines was installed.

The airliner sported a tricycle landing gear arrangement, which permitted the craft to sit level and low to the ground, allowing for easy passenger boarding and deplaning, and baggage and cargo handling. Because of its high-wing, low-to-the-ground design, refueling was uncomplicated, and the engines were easily accessible for maintenance when the aircraft was parked.

Douglas also employed the high-wing concept in the creation of its military DB-7 (A-20 Havoc) aircraft. Production of the DB-7s began at the company’s El Segundo factory in Southern California, the same place where DC-5s would be manufactured.

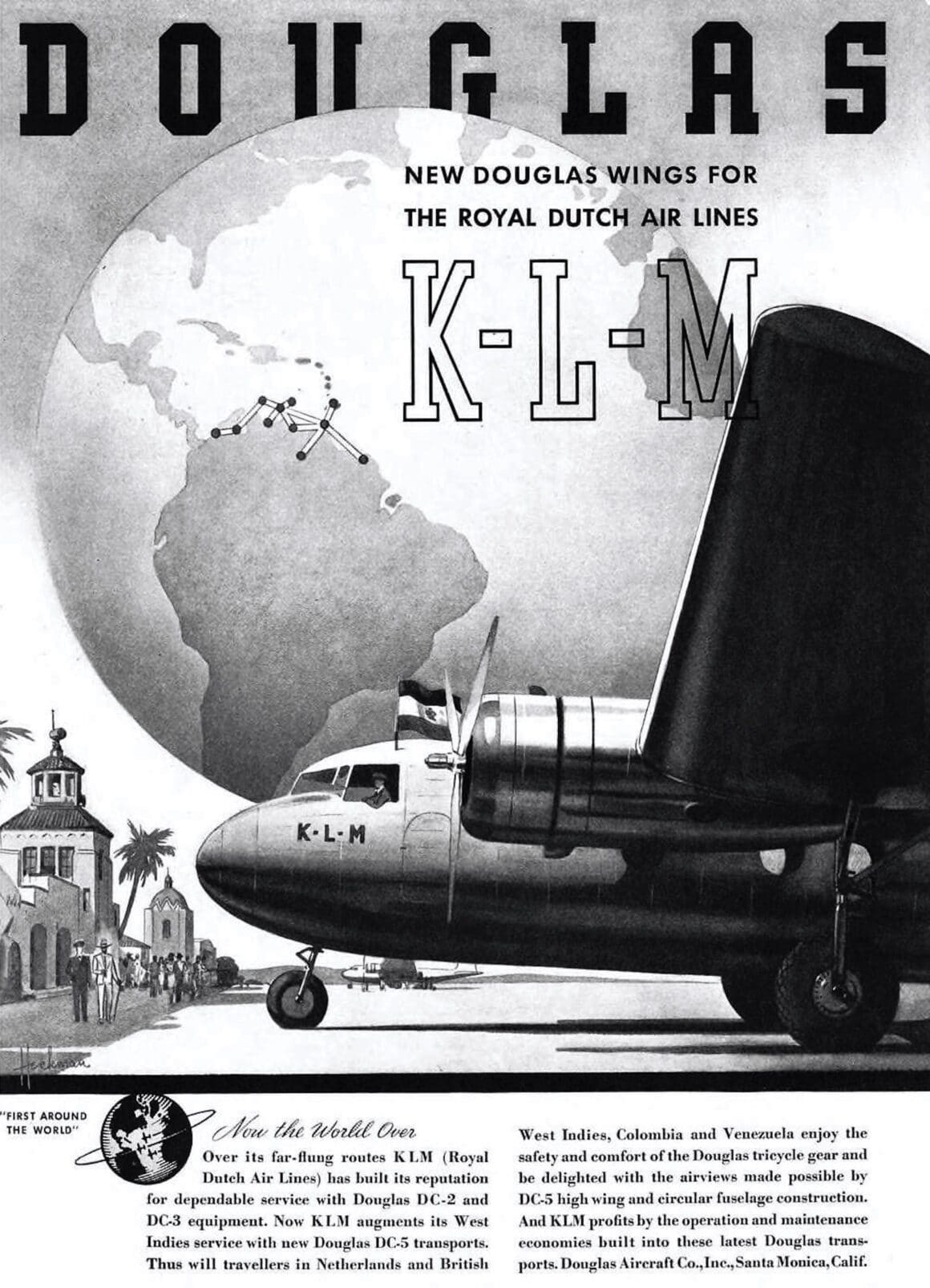

Orders began to trickle in: Pennsylvania Central Airlines (PCA – later renamed Capital Airlines) ordered six; KLM requested four; SCADTA of Colombia wanted two; and the original British Airways, which was in the process of merging with Imperial Airways to form BOAC, expressed interest in acquiring nine examples in August 1939.

In addition to civilian orders, seven were requested by the military: three for the U.S. Navy (designated R3D-1s) and four for the Marine Corps (R3D-2s).

WAR BREAKS OUT IN EUROPE

The market for the DC-5 was shaky to begin with. It was designed specifically for “the short-haul operator serving a low-revenue territory”, a market that would not truly develop until 1945 when the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) began certificating local service (or “feeder”) airlines.

Just as the DC-5 was ready to make its debut, war broke out in Europe. The British government decided to spend money on military aircraft instead of DC-5s for British Airways. SCADTA in Colombia, which had been a creation of that nation’s German expatriate community, was forced to change ownership and merge with a competitor, forming AVIANCA. The DC-5 order was cancelled.

And in the United States, PCA’s management decided that their airline, too, could forgo the new Douglas airliner. That left only KLM’s order for four examples on the books along with the military variants. With the loss of several DC-5 orders, the decision was made to commit the El Segundo plant solely to the manufacture of military aircraft.

In all, only 12 DC-5s were built: the prototype plus four for KLM and seven for the Navy and the Marines.

The prototype aircraft found an unusual buyer. William (Bill) Boeing, founder of the Boeing Airplane Company, purchased the first DC-5 to use as his personal aircraft and christened it Rover.

IN SERVICE WITH KLM

KLM requested that three of its DC-5s be outfitted with 22 seats and one with 18. All four were intended for use on short-haul routes from Amsterdam, but with war engulfing Europe, KLM’s management redirected the DC-5s to its colonial divisions.

Two – PJ-AIW (christened Wakago, meaning Wild Goose) and PJ-AIZ (Zonvogel, or Sun Bird) – were delivered to Curacao, base of the Dutch West Indies division. The other two – PK-ADA and PK-ADB – were shipped to Batavia (modern-day Jakarta, on the island of Java), the headquarters of KNILM, KLM’s subsidiary in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia).

After serving for a year in the Caribbean, the DC-5s based in Curacao were flown to the Douglas factory in Southern California to be dismantled and shipped to Batavia, where they would join the other two DC-5s serving with KNILM. PJ-AIW became PK-ADC, while PJ-AIZ (Zonvogel) was reregistered PK-ADD.

Now, KNILM possessed all four commercial DC-5s in existence. All went relatively smoothly until the Japanese forces invaded Java. PK-ADA was damaged and captured by the Japanese, who repaired it, then flew it to Japan, where it served the military for training purposes.

Filled with refugees, PK-ADB, -ADC, and -ADD evacuated to Australia that month (February 1942) under the command of KNILM crews.

AND THEN THERE WAS ONE

Wartime control of the three airliners was quickly taken from their Dutch operator and placed under the supervision of the Allied Directorate of Air Transport (ADAT). Under ADAT, Australia’s commercial airlines performed wartime duty by flying transport aircraft that had been requisitioned by the military. The DC-5s were given new call signs in Australia: they became VH-CXA, -CXB, and -CXC.

On 17 August 1942, VH-CXA was destroyed by fire at Port Moresby, New Guinea, after being struck during a Japanese air raid.

Then, on 6 November 1942, VH-CXB took off from Charleville, Queensland, en route to Brisbane. The aircraft made a forced landing on a strip east of Charleville after losing one of its engines. All on board survived, but the aircraft was written off and used as a source for spare parts.

The only DC-5 Left

That left one airworthy commercial DC-5 still in existence: VH-CXC, the former Sun Bird (Zonvogel), which had once plied the Caribbean skies.

In 1944, the sole remaining DC-5 airliner was released to Australian National Airways (ANA) for use on regular commercial services from Melbourne to Adelaide and Sydney, and to Hobart and Launceston on the island of Tasmania.

In July 1946, the Australian carrier retired the one remaining commercial DC-5 from service. All of the surviving military examples had been scrapped at the end of World War II. But that was not the end of the story.

In June 1947, two gentlemen, Gregory R. Board and Gregory Hanlon, founded New Holland Airways to offer “luxury charter flights to all parts of the world”. The luxury flights consisted mainly of transporting Italian and Greek immigrants from southern Europe to Australia. The nation was sponsoring a postwar immigration drive, beckoning citizens of foreign countries to relocate to Australia. The government’s catchphrase for the drive was “populate or perish”.

In January 1948, New Holland Airways purchased the retired DC-5 from ANA and christened it Bali Clipper. The DC-5 made two round-trips to Athens, Greece, to collect emigres in March and April 1948. Then, in May 1948, the last remaining DC-5 departed Sydney for Rome on its final trip for New Holland Airways.

DC-5 No longer airworthy

Details are sketchy, but Mr. Board contacted the Australian Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) from Italy to inform them that the DC-5 was no longer airworthy. That wasn’t true. Apparently, on 28 May – in a deal consummated in a hotel room in Catania, Sicily – Mr. Board sold the DC-5 to an American named Martin A. Rybakoff. The DC-5 was purchased in the name of Service Airways, an outfit that was secretly acquiring aircraft for the then-forming State of Israel’s fledgling air force.

The aircraft served in Israel, where it was damaged in a hard landing at Ramat David Airbase in October 1948. That ended its flying career. The aircraft was moved to Lod Airport (today’s Ben Gurion Airport) for use in ground-training exercises. Eventually, the DC-5’s final resting place was a children’s playground.

WHY WAS THE DC-5 PROJECT A FAILURE?

Douglas Aircraft Company’s timing for the introduction of the DC-5 could not have been worse. The world would be engulfed in war in the years immediately following the aircraft’s introduction.

After the war, there were so many war-surplus C-47s (DC-3s) available at low prices that a new DC-5 would have been too expensive for most of the fledgling feeder carriers. Lockheed’s model 75 Saturn, a postwar product that closely resembled the DC-5, failed to sell for just that reason. Had the war not transpired, the fate of the DC-5 – and the Lockheed Saturn – may have been a lot different.

The basic design of the DC-5, which was revolutionary at the time, would finally find success in the late 1950s in the form of the Fokker Friendship and its American counterpart, the Fairchild F-27. Introduced in 1958, the F-27 sported a high wing with a low-slung fuselage. But the Fairchild and Fokker types could accommodate 36 – 40 passengers instead of just 16 – 22.

The DC-5 was the only DC-series airliner that did not prove successful. And only one airline in the world can claim to have operated a version of each Douglas Commercial (DC) model from the DC-2 through the DC-10: KLM Royal Dutch Airlines.

3.20.22