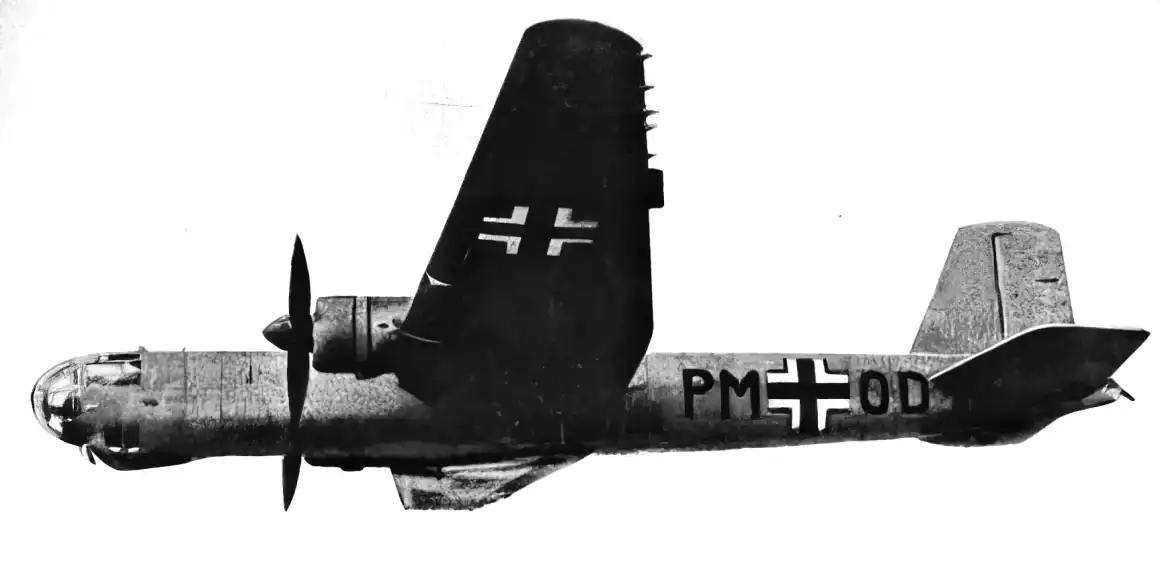

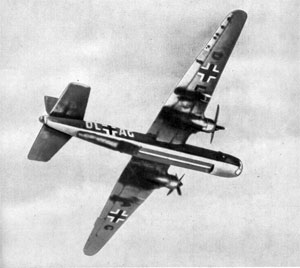

During the buildup to World War II, Germany wanted to develop a long-range heavy bomber. Their solution was the Heinkel He-177 Greif.

The design included advanced, unique features Germany hoped would make it a powerful weapon in the coming war. However, many problems kept the Greif from becoming an effective part of the Nazi war machine.

It eventually earned the nickname “The Flaming Coffin,” which gives a good indication of the plane’s success.

German Planning for New Heavy Bomber Began in the Years Leading Up to World War II

From the beginning of the project in 1936, the German Air Ministry had some specific goals for it. The basic requirements were that it fly long distances and be fast enough to outfly Allied fighters. Specifically, they planned for it to carry a 2,200-pound bomb load 3100 miles at about 311 miles per hour. The Germans tasked the Heinkel company with designing and building the new bomber.

The Greif had a wingspan of 103 feet and a length of 72 feet, similar in size to the American B-17. Initial plans were for it to have four V-12 engines mounted along the wings. A later change to this became one of the aircraft’s most significant problems.

Heinkel designed the Greif to have a cockpit crew of three: pilot, co-pilot, and gunner. There was a turret on the starboard side of the nose to defend against frontal attacks and another below the nose. The design allowed the gunner to operate them remotely. There was also a tail gunner who would fire his own gun. Several years later, Heinkel added a dorsal turret with two 13-millimeter guns.

Major Issues with First Prototypes

Many problems quickly arose, beginning with the initial flights of the Greif prototypes. One of the first problems was that the technology had not advanced far enough for the planned remote-control guns to function. As a result, Heinkel converted the turrets to manned positions.

Another problem came when the Germans decided to add a unique capability to the Greif. Ernst Udet, Nazi Director General of Air Force Equipment, decided the new aircraft should be capable of dive bombing. Dive bombing was different from the high-altitude bombing used by the B-17 and other Allied bombers. To make this possible on the Greif, Heinkel had to reinforce the aircraft’s undercarriage. This modification was made so that it could withstand the extreme stress put on the aircraft from pulling out of a steep dive. The modifications were essential for the Greif to have powerful enough engines to manage the weight.

Engine Design: The Source of Most of the Greif’s Problems

The first design called for engines with 1,973 horsepower. However, these engines did not exist in 1937, so Heinkel decided to use Daimler-Benz DB 606-A engines instead. They also felt that four engines mounted on the wings would not be aerodynamically sound, interfering with the plane’s dive-bombing ability.

Heinkel then chose to install two side-by-side engines in a single nacelle on each wing instead. They felt this would reduce drag on the airframe and make dive bombing possible. Each pair produced a combined 2700 horsepower. More than anything, this led to the eventual failure of the Greif. The engine pairs would drive a single airscrew shaft gear to turn the propellers. They realized excessive heat was a potential problem with two engines so close together.

Innovative Cooling System Failed to Meet Goals

Designers developed an innovative idea for a cooling system involving the pressurization of coolant water. Once the engines heated it to its boiling point, it would move to an expansion area and become steam. The steam would then cool as it passed through pipes under the outer skin of the fuselage and wings.

Eventually, however, they found that this system could not cool the two engines. They resorted to installing conventional radiators behind each propeller. While this seemed to work, it also increased the aircraft’s gross weight even more.

Frequent Fires Due to Oil Leaks in Engine Nacelles

Another problem was that oil would leak into the tight space between the engines. The oil would often drip on the hot exhaust manifolds on the other engine and catch fire. Another oil-related problem occurred during early test flights. Designers discovered that the engine oil return pumps caused the oil to foam when pilots throttled the engines back at altitude. The oil then became ineffective, resulting in overheating and the failure of several bearings, which sent connecting rods through the engines.

Designers also tried to save weight by not installing a firewall between engines, which only worsened the heating problem. An additional problem was that the tight spaces in the nacelles made it difficult for maintainers to reach engine components. They then performed less routine maintenance, which only led to more problems.

Design Flaws Resulted in Multiple Crashes

Looking back, it is unsurprising that these design flaws led to critical problems in flight. In November 1939, during the first flight of the Greif prototype, pilots had to land after just 12 minutes when the engines overheated. During the second flight, the aircraft had severe control problems and disintegrated in the air.

Later, the fourth prototype failed to recover from a shallow dive and crashed in the Baltic Sea. In 1941, two more prototypes caught fire and crashed. Despite these failures, pilots had favorable opinions about the Greif, and Germany continued with the program.

Germany Ultimately Abandons Heavy Bomber Project

In 1942, the Nazi High Command ordered the Luftwaffe to destroy the British fleet, and Heinkel produced 130 of the aircraft in 1943. Eventually, Germany built almost 1200 Greifs. Although they flew some combat missions, they never achieved the success the leaders hoped for. Germany was facing shortages in components and materials due to the Allied bombing of manufacturing facilities. The Nazis also had to focus on fighter production to defend against Allied attacks. Finally, in 1944, Germany abandoned the Greif program.