Throughout aviation history, many aircraft have featured a push-pull engine configuration.

Propeller-driven planes often rely on forward-mounted engines to pull them through the air. Some have engines mounted in the rear of the fuselage, which operate as pushers.

The push-pull concept offers some of the advantages of both designs. Although not ideal for all aircraft, the push-pull structure provides some significant improvements over other designs.

Different Versions of Push-Pull Engine Configuration

There are multiple ways push-pull configurations are used on aircraft. A common concept has two propellers, one forward and one aft, aligned along the fuselage centerline. Some of these designs have multiple engines working in tandem to turn the propellers. Other models feature a combination of standard puller-type engines and others in different locations that operate as pulling powerplants.

The push-pull engine configuration offers several key advantages. By placing both propellers along the aircraft’s centerline, the design maintains the aerodynamic balance and symmetry of a single-engine aircraft. This setup also reduces drag compared to wing-mounted engines, improving overall efficiency.

Another significant benefit is enhanced safety. In the event of an engine failure, push-pull aircraft are easier to control. Push-pull designs remain more stable than conventional twin-engine aircraft with wing-mounted engines, which tend to yaw sharply toward the inoperative engine. This feature helps pilots maintain control, even at lower speeds where conventional twins can become uncontrollable due to a condition known as Minimum Controllable Airspeed (Vmc).

Military Applications for Push-Pull Designs

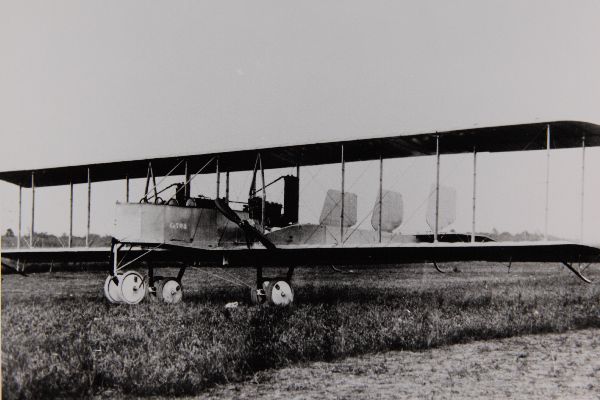

Push-pull engine configurations have been a feature on some military aircraft since the First World War. One of the earliest examples was the Kennedy Giant, an experimental British heavy bomber prototype. It had four Canton-Unne Salmson Z9 engines–two in a pulling configuration and two as pushers.

The aircraft was built by C.J.H. Mackenzie-Kennedy’s company, which he founded in 1909. However, the project faced challenges from the start. During construction, the team discovered the aircraft was too large to fit through the hangar doors.

When the Kennedy Giant finally made its only test flight in 1917, it managed little more than a brief hop—the engines simply couldn’t generate enough power to lift the nearly 19,000-pound bomber effectively.

After the war, aircraft designers grew wary of push-pull configurations for most military planes. They found that during crash landings, the crew risked being crushed between the two engines if they were mounted fore and aft in the center of the fuselage. And in the event of a bailout, there was the added danger of striking the rear propeller. These safety concerns ultimately limited the push-pull layout’s use in combat aircraft.

Licensing Limitations for Push-Pull Aircraft Pilots

Another interesting complication with push-pull aircraft is how they affect pilot certification.

Pilots who earn a multi-engine rating in aircraft with centerline thrust–a defining feature of push-pull configurations–are limited to flying that specific type. Their license does not authorize them to fly conventional multi-engine aircraft with wing-mounted engines. In contrast, pilots trained on wing-mounted engine aircraft can legally operate both types without restriction.

Caproni Ca. 1 Had Three Engines: Two Pulling and One Pushing

Multiple aircraft designs have used push-pull engine configurations over the years. One of the more unusual early designs was the Caproni Ca.1, introduced in 1914. This Italian bomber featured three engines: two 80-horsepower Gnome et Rhône rotary engines mounted on the tail booms operating as pullers or tractor propellers, while a third 100-horsepower engine positioned behind the central fuselage functioned as a pusher.

Bellanca “Blue Streak”: A Tragic End to an Ambitious Design

Another unique push-pull aircraft was the 1929 Bellanca TES X-855e “Blue Streak.” Equipped with two 450-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines–one mounted in front of the cabin nacelle (or passenger compartment) and the other behind–it featured dual three-bladed propellers. In 1930, engineers replaced the engines with more powerful 600-horsepower Curtis Conquerors.

However, tragedy struck during a cargo flight that same year. Loaded with cargo, the aircraft experienced severe vibrations in the rear propeller’s drive shaft. This tore the plane apart mid-flight, killing its three-man crew.

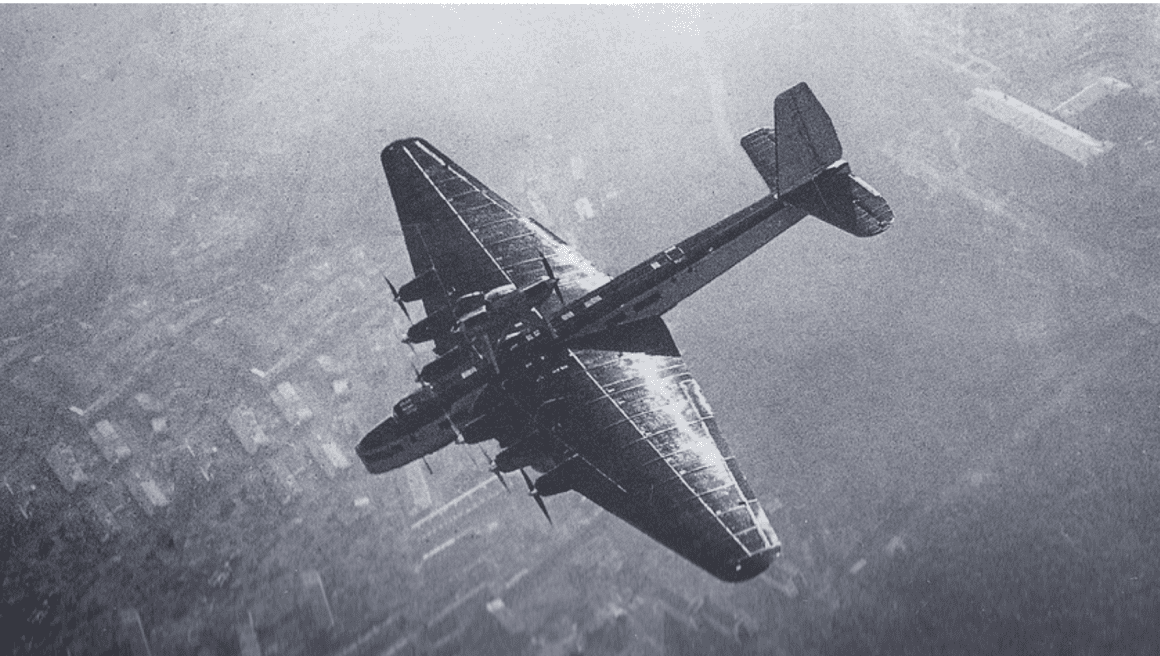

Fokker F-32 Designed for Luxury Travel

The Fokker F-32, built in 1929, was one of the first push-pull aircraft designed specifically for commercial service and the first four-engine airliner. Powered by Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial powerplants, it could carry up to 32 passengers. Its Dutch manufacturer, GKN Fokker, designed it to be a comfortable, luxurious way to travel.

Two engines were mounted in two nacelles under each wing, each with propellers fore and aft. Fokker hoped the F-32 would increase range compared to other airliners of that time. However, the aircraft was notorious for high fuel consumption and excessive maintenance needs. Eventually, due to economic conditions during the Great Depression, Fokker ended the project.

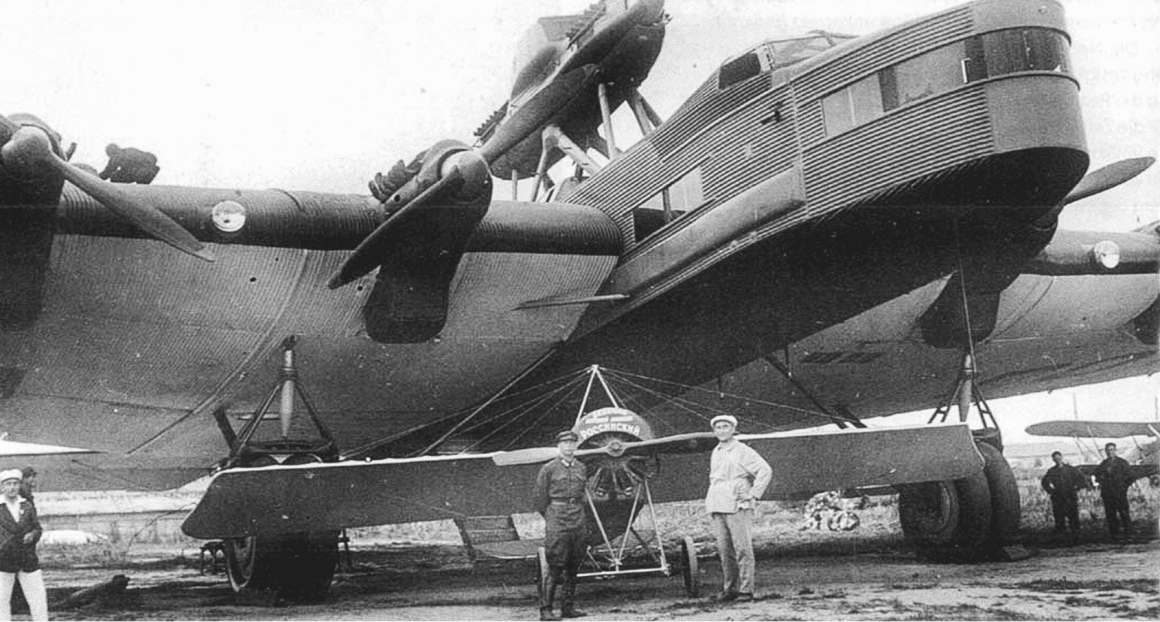

Eight Engine ANT-20 Largest Aircraft in The World in 1930s

The Soviet Tupolev ANT-20 “Maxim Gorky” was designed and built in the 1930s. They created it to be the largest aircraft in the world at the time. It had a wingspan of 206 feet, wider than that of a B-52, and a length of 107 feet. The ANT-20 was powered by eight Mikulin AM-34FRN V-12 liquid-cooled piston engines. They were rated at 1200 horsepower each, but the plane cruised at a relatively modest top speed of 140 miles per hour.

The engine layout was unconventional: three engines mounted under each wing operated as pullers. In contrast, an additional engine mounted atop each wing featured a rear-facing propeller at the rear of the nacelles that functioned as a pusher.

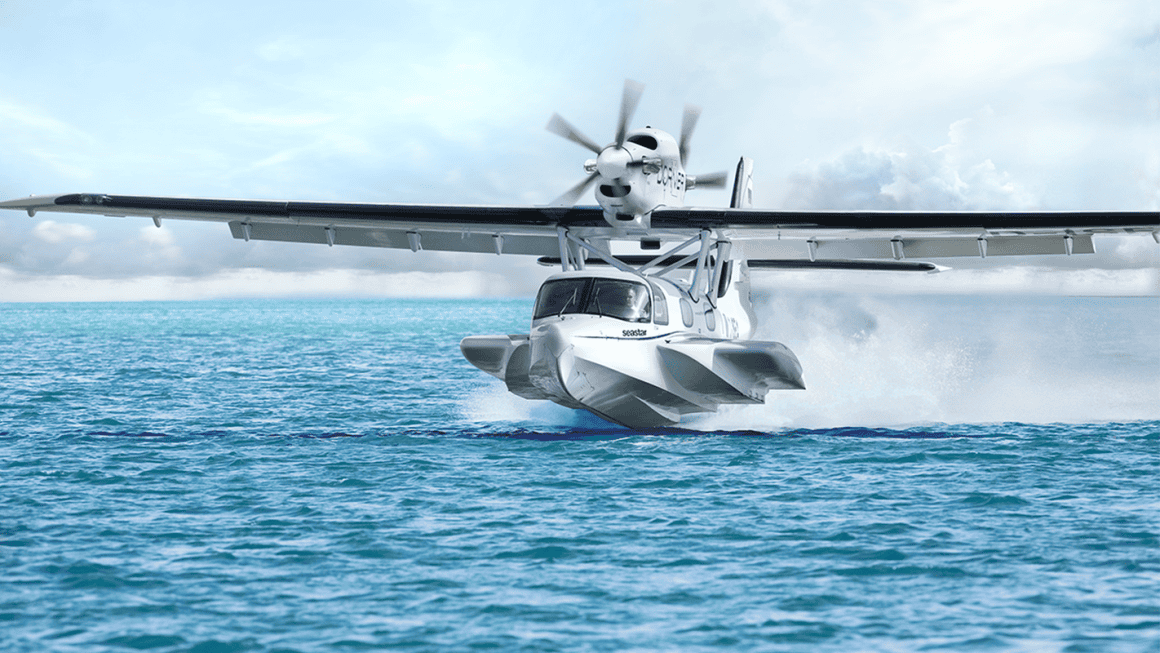

Cessna Skymaster a Modern Version of Push-Pull Engine Configuration

Decades later, the Cessna 337 Skymaster brought push-pull design into the modern era. First introduced in 1969, Cessna produced 2,993 of the type, making it one of the most recognizable aircraft with a push-pull engine configuration.

The Skymaster featured two 201-horsepower air-cooled Continental engines—one mounted in the nose (puller) and the other behind the passenger cabin, just ahead of the tail (pusher). This layout offered better visibility and eliminated asymmetric thrust issues during engine failure, a key selling point for general aviation pilots.

Despite its popularity, the Skymaster wasn’t without flaws. The rear engine often suffered from cooling problems, and the aircraft was notoriously loud. The turbulent airflow from the front propeller interfered with the rear propeller, amplifying noise and reducing efficiency.