On 5 August 2025, Ravn Alaska shut down operations for the second—and final—time.

The Anchorage-based regional carrier, long considered a cornerstone of Alaska’s intra-state connectivity, quietly folded after nearly 77 years of service. Its collapse leaves behind a fragmented regional network and raises concerns about the long-term viability of rural air service in one of the most aviation-dependent regions in the world.

The company’s last flight, operated between Valdez Airport (VDZ) and Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport (ANC), touched down without ceremony. Days later, the airline’s website displayed a final statement: “We appreciate the years of service we were able to provide to Alaska communities. While we are no longer operating flights in Alaska, we’re grateful for the trust you placed in us during our time serving the region.”

Current CEO Tom Hsieh confirmed to the Anchorage Daily News that all flights “have been canceled.” No official figure has been released on job losses, though the carrier employed at least 270 people at the time of closure.

From Bush Beginnings to Regional Mainstay

Ravn’s origins stretch back to 1948, when pilot Carl Brady founded Economy Helicopters. Under US government contracts, Brady flew Bell 47s to map Alaska’s vast and unmapped interior (remember: Alaska wasn’t granted statehood until 1959). In the 1950s, the company became Era Helicopters, and in 1967, it was purchased by Houston-based offshore drilling contractor Rowan Companies. Initially used to support oil exploration and the construction of the Alyeska Pipeline, Era expanded into fixed-wing operations with De Havilland Twin Otters and Convair 580s to serve isolated towns.

By 1983, Era Aviation had evolved into a scheduled passenger carrier, connecting communities such as Valdez, Kenai, Kodiak, Cordova, Bethel, and Homer. Over the following decades, a web of mergers—including Hageland Aviation and Corvus Airlines—and acquisitions such as the 2017 purchase of defunct Yute Air’s assets, formed what became known as the Ravn Air Group.

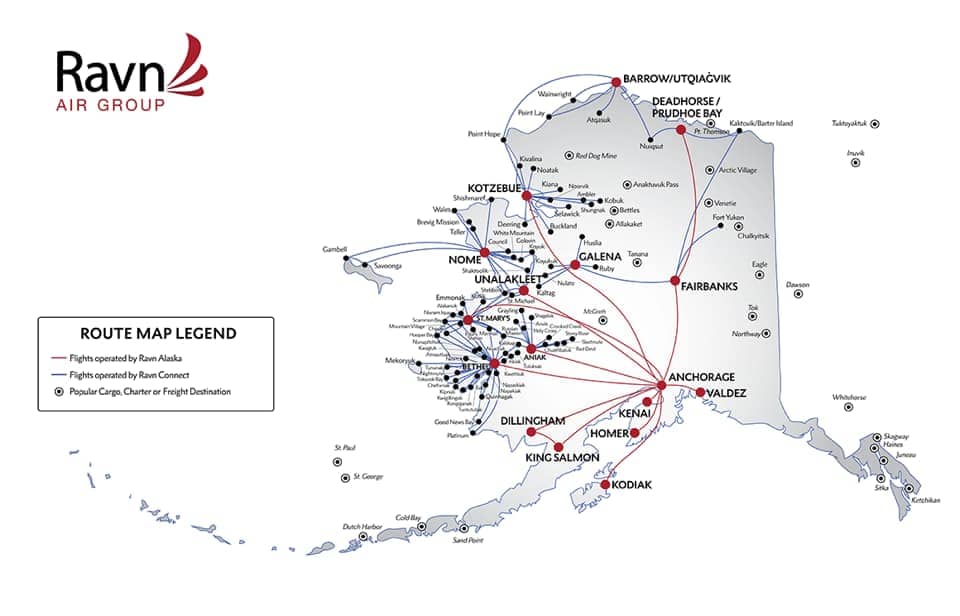

Rebranded Ravn Alaska in 2014, the airline at its height operated more than 70 aircraft to over 100 destinations, including many communities accessible only by air. Its fleet history is a cross-section of Alaskan bush flying itself: Beechcraft 1900s, Cessna Caravans and 207s, Piper Navajos, Twin Otters, Convair 580s, Dash 7s, and finally, its core fleet of Dash 8-100s and -300s.

Ravn Alaska Fleet History (1948–2025)

| Era | Aircraft Type | Role/Notes |

| 1948–1960s | Bell 47 | The starting point — Carl Brady’s Economy Helicopters used Bell 47s for U.S. government mapping contracts, helping chart Alaska’s still-unmapped interior. |

| 1950s–1970s | De Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter | Early bush operations expanded to fixed-wing; rugged STOL performer ideal for short gravel strips and lake landings. |

| 1970s–1980s | De Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter | A workhorse in Alaska’s villages; reliable in extreme cold and short-field environments, connecting communities without paved runways. |

| 1970s–1990s | Convair 580 | Era’s first real “mainline” aircraft; carried passengers and cargo on longer routes such as Anchorage–Bethel and Anchorage–Kodiak, often in challenging weather. |

| 1970s–1980s | Piper Navajo | Twin piston aircraft for low-volume scheduled service and light cargo, bridging the gap between bush planes and larger turboprops. |

| 1980s–1990s | Cessna 207 | A true village lifeline; carried mail, groceries, and passengers to isolated settlements on some of Alaska’s shortest and roughest strips. |

| 1980s–2010s | Beechcraft 1900C/D | Staple of commuter and EAS operations; served small towns on tight schedules, often as the only link to the road system. |

| 1980s–2000s | Cessna 208 Caravan | A versatile passenger/cargo hauler; suited for mixed loads and flexible routing, frequently flown in marginal weather. |

| 1980s–1990s | De Havilland Canada DHC-7 Dash 7 | Four-engine STOL turboprop used on runways too short for most regional aircraft, including some Aleutian and bush destinations. |

| 2010s–2025 | De Havilland Canada DHC-8-100 (37-seat) | The backbone of the revived Ravn fleet under FLOAT Shuttle; served 12 key Alaskan destinations until the 2025 shutdown. |

| 2010s–2025 | De Havilland Canada DHC-8-300 (50-seat) | Single example used on higher-demand routes; offered more seats while retaining short-field capabilities. |

Turbulence During the Pandemic

In April 2020, COVID-19 grounded Ravn’s fleet and forced a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing. The sudden halt stranded thousands in rural Alaska, prompting state and federal agencies to scramble for emergency service providers.

The airline’s assets were purchased later that year by California-based FLOAT Shuttle, which relaunched Ravn in late 2020 with a trimmed-down fleet of Dash 8-100s and a renewed focus on scheduled passenger service to 12 core destinations.

Modernization Dreams, Unmet

Under FLOAT ownership, Ravn leaned into a sustainability narrative, announcing a 2021 letter of intent for 50 electric short takeoff and landing (eSTOL) aircraft from Airflow. This was followed by an MOU with ZeroAvia to explore hydrogen-electric retrofits for its Dash 8 fleet. While the announcements generated industry buzz, neither project reached implementation before the airline’s final grounding.

Retrenchment and Fleet Pressure

By 2024, warning signs had returned. Ravn trimmed service to parts of the Aleutians, laid off 130 employees, and withdrew from certain Essential Air Service (EAS) routes. Then, in early 2025, the airline informed the US Department of Transportation of a “significant and unanticipated” reduction in available aircraft after Canadian lessor Avmax declined to renew leases on multiple Dash 8-100s.

With few viable replacements in the market and capital constraints limiting options, the network rapidly unraveled.

A Silent Departure

The final shutdown came with little public forewarning. On 5 August 2025, Ravn stopped all flights and quietly informed regulators and partners. The rapidity of the exit contrasted sharply with the high-profile 2020 grounding.

Ravn was the artery between the bush and the world. When it stopped, everything slowed down.

Former Ravn Alaska pilot

For many in rural Alaska, the impact was immediate. As one former pilot described, “Ravn was the artery between the bush and the world. When it stopped, everything slowed down.”

Parent Company: New Pacific’s Narrower Horizons

Ravn’s parent company, New Pacific Airlines, remains operational but in drastically scaled-back form. Originally launched in 2022 under the name Northern Pacific Airways, the startup aimed to replicate the Icelandair model by connecting North America and Asia through Anchorage with a fleet of aging Boeing 757-200s, initially delivered to USAir in the early 1990s. However, persistent regulatory delays and shifting market conditions have kept the airline from launching scheduled service. Today, New Pacific operates only charter flights.

Interestingly, New Pacific’s own corporate heritage traces back to Ravn’s roots, founded on 20 June 1948, as Economy Helicopters. In a twist of aviation lineage, the same entity that began with a single Bell helicopter mapping Alaska has ended its scheduled passenger operations, now surviving only through its charter division.

Implications for Rural Aviation

Ravn’s demise underscores the fragility of high-cost, low-margin regional aviation in extreme geographies. Alaska’s vast distances, unpredictable weather, and heavy reliance on air service make carriers particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in fuel costs, aircraft availability, and labor markets.

While carriers such as Ryan Air, Grant Aviation, and Alaska Airlines’ Ravn Connect partners have stepped in to cover certain routes, no operator matches Ravn’s former scale. The long-term consequences for rural connectivity remain uncertain.

For much of its history, many Alaskans considered Ravn not just an airline but part of their state’s infrastructure. Its flight schedules were the lifeblood of villages, clinics, and supply chains across a state where road access is the exception, not the rule.

The Alaska skies are quieter now, but the need Ravn once met remains: urgent, constant, and still without a clear solution.