Amazing, awe-inspiring, and impressive are all adjectives that capture the size, capacity, range, and luxury of the eight-engine intercontinental Bristol 167 Brabazon airliner—all the more so because it first took to the sky at the end of the 1940s. But its success hardly matched its accolades.

Design Origins of the Bristol 167 Brabazon

During the so-called “Golden Age of Aviation,” which occurred during the two-decade, 1919-to-1939 inter-war period, commercial aircraft incorporated greater advancement, speed, comfort, and range. By the dawn of World War II, the configuration of the large-capacity, long-range airliner had been established with a low wing, four piston engines, and a retractable tricycle undercarriage—in which form the Douglas DC-4 and the Lockheed Constellation appeared before the war itself temporarily suspended further development.

The goal, aside from greater sophistication and safety, was to cover the coveted US transcontinental and transatlantic routes without requiring intermediate refueling stops, and Boeing, Douglas, and Lockheed all strove to achieve it.

Concentrating on military aircraft, the UK mostly ceded the design and development of commercial transports to them.

“With UK aircraft production solely concentrated on military requirements during World War II, the provision for the production of transport aircraft was the province of the American allies, who produced such notable designs as the DC-3, the DC-4, and the C-69 Constellation,” according to BAE Systems’ “Bristol 167 Brabazon” entry. “With the coming of peace, this left Britain with no modern commercial aircraft either in production or at the design stage other than the simple conversion of military transport aircraft.”

The Brabazon Committee, established on 23 December 1942 under the leadership of Lord Brabazon of Tara—who himself was issued the Royal Aero Club’s first aviator’s certificate—sought to assess potential post-war structural, powerplant, and system development for the purpose of incorporating their advancements into specific market-filling designs for both the UK and its Commonwealth countries.

Its Brabazon Report ultimately identified the following four requirements to be filled by selected aircraft manufacturers.

- Type 1: A very large transatlantic airliner.

- Type 2: A short-range transport.

- Type 3: A medium-capacity airliner for European routes.

- Type 4: A jet airliner with 500-mph speeds.

The major designs to result from the last three categories included the following.

- Type 2A: The Airspeed AS.57 Ambassador.

- Type 2B: The Vickers V.630 Viscount, the world’s first commercial turboprop.

- Type 3: The de Havilland DH.104 Dove piston commuter.

- Type 4: The de Havilland DH.106 Comet, the world’s first jetliner.

The first category led to the still-born Bristol 167 Brabazon.

Design Features of the Bristol 167

Because the Bristol Aeroplane Company had already conducted studies of large bombers, such as the Type 159, and because it had explored potential transatlantic airliners by analyzing their capacity, weight, and range parameters, it was logically chosen to fulfill the Brabazon Committee’s Type 1 requirement.

Its 1937 bomber design served as its early foundation. Revised and fitted with Bristol Centaurus engines, it first closely matched the Air Ministry’s 1942 need for a military aircraft capable of accommodating a 15-ton bomb load because of its projected 225-foot wingspan, eight powerplants, and 5,000-mile range. Transatlantic capability was more than within its realm.

Although its long design interval prompted the Air Ministry to further develop the existing Avro Lancaster bomber, Bristol’s investment was not without value, since a further modification enabled it to fill Air Ministry Specification 2/44 for the Type 1 very large airliner requirement.

As a result, the Committee announced on 11 March 1943 that it had authorized preliminary design work of such an aircraft. It ultimately issued a contract for the production of a pair of prototypes.

Named after Lord Brabazon himself, the Bristol 167 was truly staggering for its time.

Featuring a 177-foot-long, 25-foot-diameter, circular cross-section fuselage, which facilitated six-abreast internal seating, it used non-standard skin gauges to cater to local stress areas and thus reduce structural weight, while incorporating new machine methods and dope-sealed rivets.

Its massive, low-mounted airfoils, with 4-degree, 16” outer leading-edge sweep and a 14-degree, 56” inner one with dihedral, progressively decreased in chord from 31 feet at the root to 10 feet at the tip. Low-speed lift was attained by means of two-section trailing edge flaps, and lateral axis control was achieved by means of outboard ailerons. So thick were the wings that a person six feet in height could stand up inside them, and their 230-foot span exceeded that of the turbofan Boeing 747-100 of two decades later by almost 35 feet.

Power was provided by eight 18-cylinder, wing-imbedded Bristol Centaurus 20 piston radial engines, each angled at 32 degrees to a central driveshaft and turning two contra-rotating, reversible-braking propellers. Their rating varied from 2,500 hp on takeoff to 1,640 hp in cruise.

It rested on twin nosewheels and four-wheeled main undercarriage units.

It had a 169,500-pound empty weight and a 290,000-pound gross one.

It introduced numerous “firsts”—namely, fully-powered controls, electric engine controls, high-pressure hydraulics, and a gust alleviation system.

Wing tank-carried fuel, totaling 13,650 gallons, gave it a 5,460-mile range.

“One of the high adventures of British civil aviation, it will cross the Atlantic at 350 mph, seven miles above the sea…the Brabazon should be well ahead of its rivals, and we look ahead to it with great expectations as a new Queen Elizabeth of the air,” Lord Nelson, Minister of Civil Aviation, stated about the Brabazon, as reported in Alexander Mitchell’s and Dr. Omar Memon’s “Britain’s Piston Engine Transatlantic Hope: The Story of the Bristol Brabazon” article (Simple Flying, 7 August, 2024).

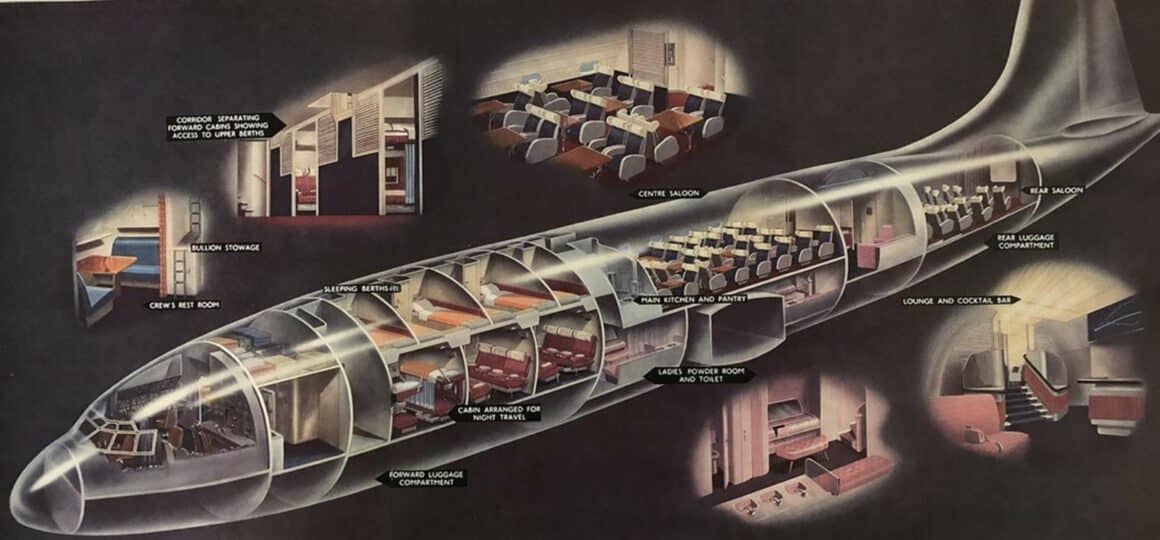

Although the mammoth airliner could technically have accommodated some 300 in a high-density single-class arrangement by today’s standards, it was designed for 96-day or 52-night passengers, the latter in sleeping berths, vying with the ship and striving to become the ocean liner of the air—in the process attracting the wealthy and consequently sparing no luxury.

“It was (envisioned) at the time that the wealthier passenger would consider air travel over lengthy sea voyages if the experience were made significantly more comfortable…,” according to BAE Systems (op. cit.).

“A design feature, which reflected the view that only those with deep pockets and accustomed to comfort were likely to fly across the Atlantic, was the generous space provided for the passengers,” it continued.

Internally subdivided into six cabins, it featured a galley, a cocktail bar, a lounge, and even a cinema, recommendations often made by BOAC, which was logically viewed as the type’s launch customer.

“Befitting the luxe travel proposition, meals would be taken in the dining compartment over the wing center section, and there was a separate lounge with a cocktail bar and a bullion store for passengers to use,” advises Stephen Skinner in his “Bristol Brabazon: Britain’s Biggest Aircraft Flop” article (Key.Aero, 10 May, 2022).

Construction and Flight Test Program

In what could have been a foreshadowing of what could have occurred if the behemoth airliner had ever entered service, Bristol itself was forced to significantly enlarge its Filton production facilities to accommodate it. As a result, the world’s largest airliner required the construction of the world’s largest hangar there, enabling it to house up to eight aircraft at a time. The runway, which was both widened and lengthened from its existing 2,000 feet to more than 8,000, necessitated the relocation of nearby Charlton village residents to Patchway.

Lacking very large airplane handling experience, Bristol Chief Test Pilot Arthur J. “Bill” Pegg gained it on the colossal Conair B-36 Peacemaker, with its six-turning piston and four-burning pure-jet engines, in Fort Worth, Texas.

The first and, thus far, only prototype, registered G-AGPW, was first rolled out for powerplant testing in December of 1948, but was subjected to earnest assessment on 3 September of the following year when it was subjected to a series of taxi trials.

Piloted by Pegg himself and Copilot Walter Gibb, and accommodating eight observers, the aircraft took to the sky at 11:30 a.m. from Filton Aerodrome on 4 September at a 200,000-pound gross weight.

“On 4 September 1949, a small army of technicians swarmed Filton Airfield, hundreds of cyclists gathered at vantage points, and around 10,000 more people arrived to witness the first flight of what promised to be a new era of passenger travel,” the Bristol Aero Collection described the experience in its “Aerospace Bristol to Celebrate 75th Anniversary of Bristol Brabazon’s Maiden Flight” entry.

The aircraft, still unpressurized, climbed to a 3,000-foot altitude and achieved a 160-mph speed, but touched down 26 minutes later at about 115 mph.

The British press proclaimed that “the queen of the skies (is) the largest landplane ever built.”

Four days later, the single prototype was displayed at the Farnborough Air Show, but actually flew at it the following year, along with practicing takeoffs and landings at what would become London’s Heathrow International Airport.

Program Cancellation

Targeted at BOAC, the Bristol 167 Brabazon was not to achieve its initial sales goal, which was immediately apparent after Sir Miles Thomas, its chairman, found it underpowered and slow to respond to control inputs during his own cockpit experience in it. Its operating cost estimates were also ultimately revised in its disfavor.

“By the time it flew in 1949, it was apparent that it was unlikely to prove an economic proposition, for the smaller DC-6 and Constellation were already operating the Atlantic route and it did not offer an increase in payload proportionate to its size,” according to Ronald Miller and David Sawers in The Technical Development of Modern Aviation (Praeger Publishers, 1968, p. 135).

The second prototype, the Bristol 167 Brabazon Mk. II and registered G-AIML, fared no better and, in fact, never saw the light of day. To have been powered by uprated Bristol Coupled Proteus turboprop engines, it would have introduced a cruise speed increase and facilitated a twelve-hour transatlantic crossing time. But it fell short of its design goals.

After a 6 million British Sterling pound investment over and above the 18 million already spent on the piston-powered prototype and requiring an estimated 2 million additional to complete, Duncan Sandys, Minister of Supply, announced the Brabazon program’s cancellation on 17 July 1953 after the only flying example had amassed 382 airborne hours during 164 sorties. Broken up, along with the still-incomplete second prototype, both ended up as scrap and a handful of parts and component displays in aviation museums.

Although British European Airways had expressed interest in operating the only flying example on holiday flights between London and Nice in a 180-passenger configuration, it had never earned its airworthiness certificate to permit such service.

Like other mega-aircraft concepts which inspired awe because of their size, capacity, and comfort, the Brabazon, which was ahead of its time and therefore required eight engines to power, was not a practical one. It was slow and sluggish. Its size would have required airport infrastructure investment wherever it flew, and its excess capacity would have limited its frequency. Nevertheless, it served as a stepping stone to later designs.

“Despite the Bristol 167 Brabazon being often thought of as a ‘white elephant,’ much of its expenditure was on the creation of an infrastructure, especially to build and support large aircraft production after the war,” BAE Systems concludes (op. cit.). “One direct beneficiary of the work instigated by the Brabazon was the enormous production facilities for the Bristol Britannia.”

That turboprop airliner filled, in many ways, the Brabazon’s intended role, but with more realistic economics and capacity.