Ozark Air Lines almost didn’t make it off the drawing board.

Back in the 1940s, the company – formed by four Missouri businessmen who were operating a small intrastate air service within the confines of the Show Me State – had applied to the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) for permission to start a local service airline (also called a feeder airline at the time) with a system based in St. Louis.

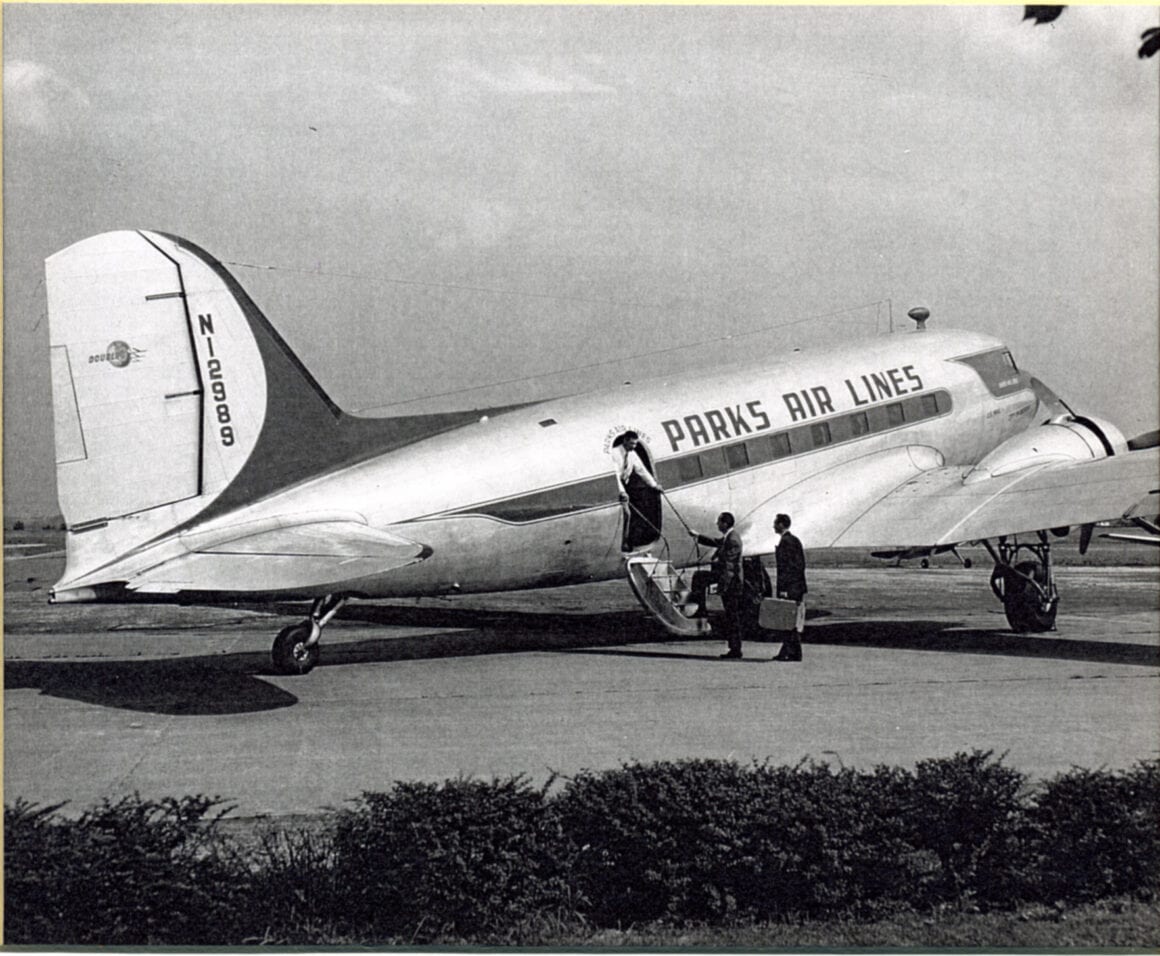

Ozark lost out to Parks Air Lines, which was founded by Oliver Parks, who operated Parks Air College in East St. Louis, Illinois.

But Parks did not act on his CAB awards. He was obviously in no hurry to inaugurate flights to the small Midwestern cities expecting airline service. It seems that members of Parks’s organization were unwilling to invest their own money in a startup airline.

The Board canceled Parks’ certificate and decided to award it to another applicant.

MR. HEYNE GETS A PHONE CALL

In late July 1950, Arthur G. Heyne – one of Ozark’s four founding executives – received a telephone call from his friend Clyde Brayton of Brayton Flying Service. Brayton was also an instructor at Parks Air College. Heyne reported that the phone call went like this:

“Congratulations!”

“For what?” Heyne replied.

“I see you just got a certificate from the CAB!”

“Aw, you’re pullin’ my leg. It’s been seven years. Are you sure it’s us?” Heyne asked.

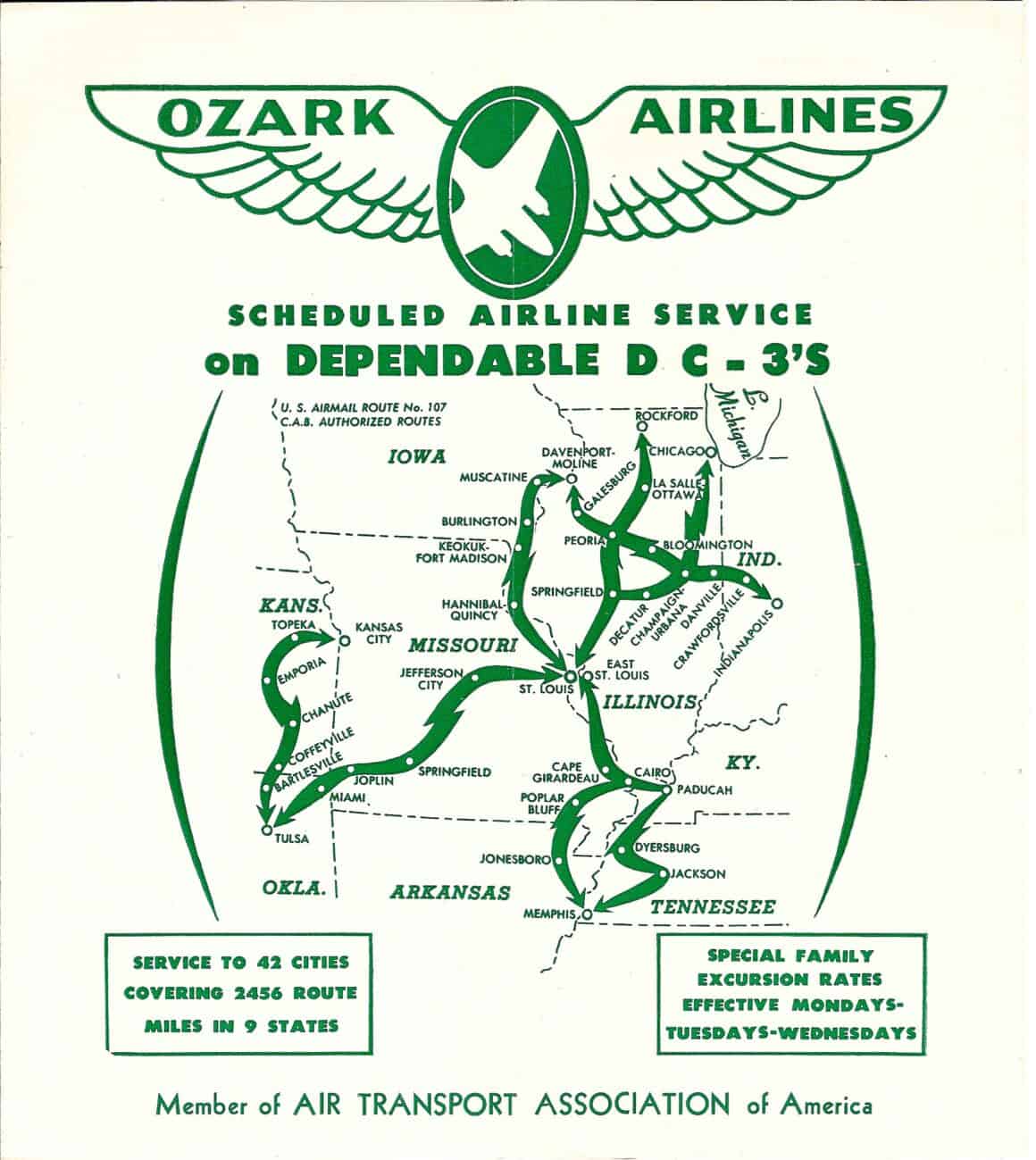

The official telegram arrived on 1 August 1950. Ozark Air Lines had, indeed, been awarded all of the routes originally given to Parks in the CAB’s Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley Cases. Ozark would be one of 13 local service airlines to serve the needs of small-town America throughout the 1950s, ‘60s, and beyond.

Ozark wisely made a deal with the Parks folks to bring Parks pilots, personnel, and a few DC-3s into the Ozark organization.

OZARK GETS AIRBORNE

Ozark’s CAB certificate became effective on 26 September 1950. On the evening of 25 September, the Ozark group gathered at the Statler Hotel in downtown St. Louis and waited for the stroke of midnight. At 00:01, the founders of Ozark officially signed the paperwork, accepting the certificate, and the airline was in business. At 06:58 that morning, Ozark’s first flight took off from St. Louis Lambert Field bound for Springfield, Illinois, Champaign/Urbana, and Chicago… with one passenger on board! That would be the first in a history of flights that lasted for 36 years.

STEADY GROWTH

In less than one year from the time of its first flight, Ozark had inaugurated service to 29 stations, covering all the routes awarded to the company as a result of the Parks Investigation Case.

Ozark’s route system grew throughout the 1950s. Like the other twelve local service airlines in the country, Ozark relied on the tried and trusted Douglas DC-3 to transport passengers throughout its Midwestern service area.

Ozark Air Lines’ DC-3s were painted in a distinctive green and white livery. To keep its aging fleet as competitive as possible, management undertook a modification program for the old Douglas airliners. Dubbed the Challenger 250 project, the goal was to upgrade the fleet to higher performance standards by installing wheel well doors, flush-type antennas, short exhaust stacks, and other enhancements, thereby transforming Ozark’s DC-3s into the most efficient in the industry.

The program was completed by September 1957, when all 20 of the company’s DC-3s had been standardized with the new equipment, and each had been configured with 27 passenger seats.

A DC-3 REPLACEMENT

As reliable as the DC-3s were, they would not last forever.

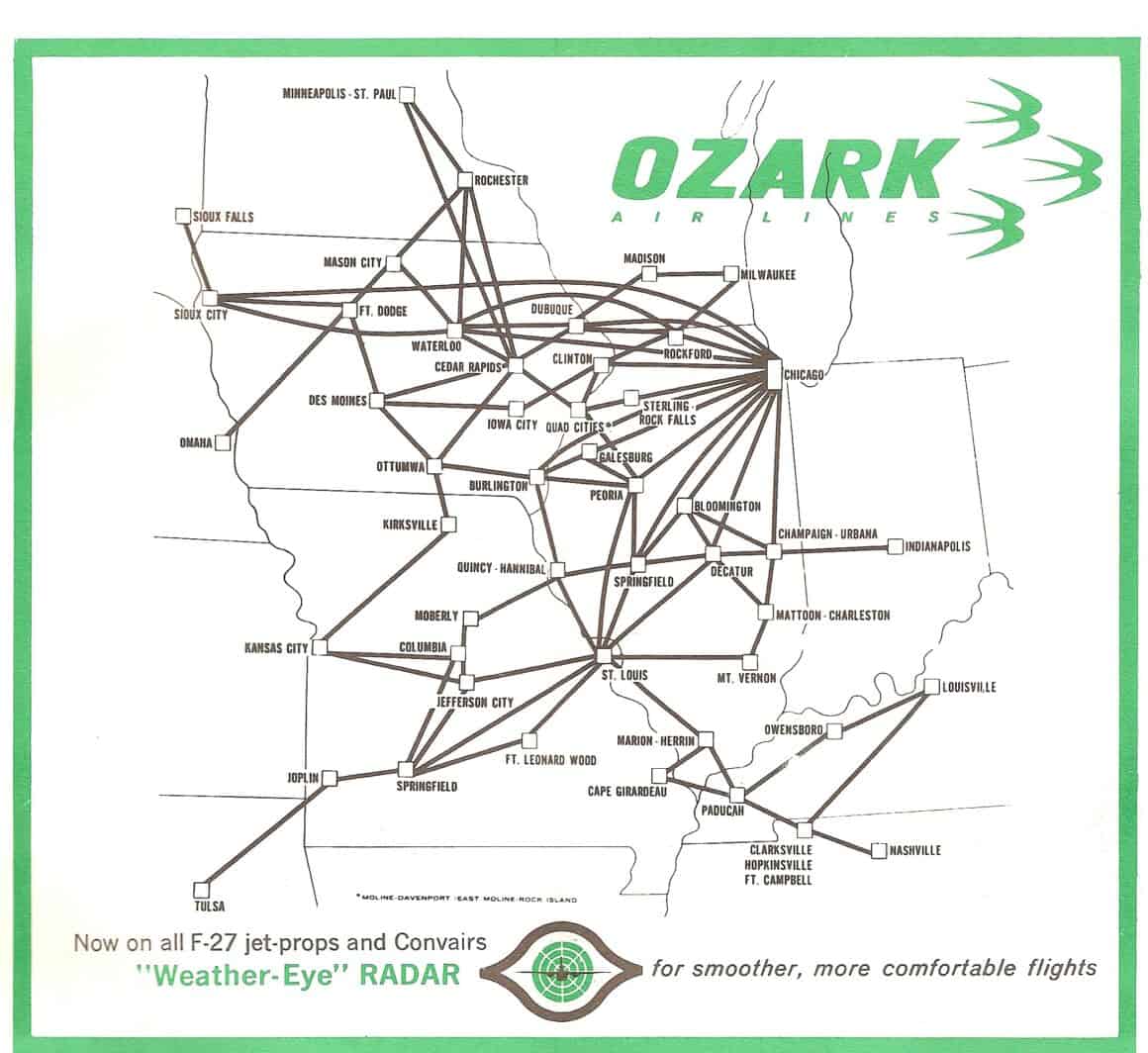

A new design called the Fairchild F-27 – an American-built version of the Dutch Fokker Friendship – became available. Referred to as a “jet prop” or “prop jet”, the turboprop F-27 employed modern technology. Carrying 40 passengers, the F-27 had two engines set into a high wing above the fuselage that gave every passenger an unobstructed view of the world below.

In December 1958, Ozark placed its initial order for three of the brand-new F-27s.

CONVAIRS AND MARTINS

When American Airlines dropped service at Peoria and Springfield, Illinois, as well as at Joplin and Springfield in Missouri, Ozark remained the only carrier serving those cities. American had served these stations using 40-passenger Convair 240s. Ozark bought four second-hand Convairs to accommodate its expanded schedule at cities formerly served by American.

Ozark Air Lines boarded its four millionth passenger on 11 September 1962, and continued adding capacity by purchasing an additional F-27 and another Convair. The company ended the year with 32 aircraft: four F-27s, five Convair 240s, and 23 DC-3s.

In 1964, the company introduced the slogan “Go-Getters Go Ozark!” Also that year, Ozark worked out a lease/trade agreement with Mohawk Airlines to take that company’s 14 Martin 404s in exchange for Ozark’s Convair 240s, a type that Mohawk had been flying since 1955. The aircraft swap began with the first Martins going into service on Ozark’s system on 1 December 1964.

INTO THE JET AGE

In January 1965, Ozark’s president, Thomas L. Grace, announced that Ozark would soon enter the ranks of pure-jet operators. Six DC-9-15s and three stretched DC-9-30s were ordered in 1965.

Grace’s plans did not stop there. He ordered yet another new type to replace the Martins and the F-27s: the Fairchild-Hiller FH-227B, an enlarged and modernized version of the F-27. The new airplane would carry 48 passengers, feature more powerful Rolls-Royce turbine engines, and be equipped with its own Auxiliary Power Unit (APU). The company placed an order for 21 FH-227B aircraft. Grace’s goal was to turn Ozark into an all-turbine-powered carrier.

Ozark’s initial DC-9 service took to the skies on 15 July 1966, from St. Louis to Chicago via Peoria. On board that inaugural jet flight was Arthur B. Skinner of Kirkwood, Missouri. Mr. Skinner had been Ozark’s very first passenger in September 1950 when a DC-3 taxied away from the gate in St. Louis with just one passenger on board… himself!

The first FH-227B service took place on 15 December 1966.

FROM CORNFIELDS TO THE BIG APPLE

The line separating trunk carriers from local service carriers began to blur as the CAB granted local airlines more permission to fly long-distance routes, allowing them to generate revenue with their new jets.

The CAB granted Ozark permission to serve Washington (Dulles) and New York (LaGuardia) nonstop from Peoria, Springfield, and Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, as well as from Waterloo, Iowa. The Waterloo to New York award – 956 miles – was the longest segment awarded to a local service carrier up until that time. Service to Washington and New York was inaugurated on 27 April 1969. In 1971, the slogan “Up there with the biggest!” was adopted.

THE SEVENTIES AND DEREGULATION

In 1973, a strike by the company’s mechanics, represented by the Air Line Mechanics Fraternal Association (AMFA), shut the airline down for 73 days. Shortly after the strike was settled, Ozark suffered its only fatal accident. On 23 July, Flight 809 – an FH-227B operating between Nashville and St. Louis via Clarksville/Hopkinsville/Fort Campbell, Paducah, Cape Girardeau, and Marion/Herrin – crashed while on final approach to St. Louis in a thunderstorm. Of the 44 aboard, 37 passengers and the flight attendant perished.

Ozark’s management team was vehemently opposed to the concept of deregulation, but on 24 October 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act into law. The CAB would slowly be phased out of existence, and a dramatic new world of airline economics would take hold of the industry.

In 1979, the Association of Flight Attendants (AFA) shut the airline down with a 53-day strike. Shortly after recovering from that work stoppage, Ozark’s operations were again brought to a halt in 1980 with a 38-day strike by mechanics. To generate cash while the flight attendants were on strike, the company sold its two factory-fresh Boeing 727-200s, which had never been put into service.

THE EIGHTIES

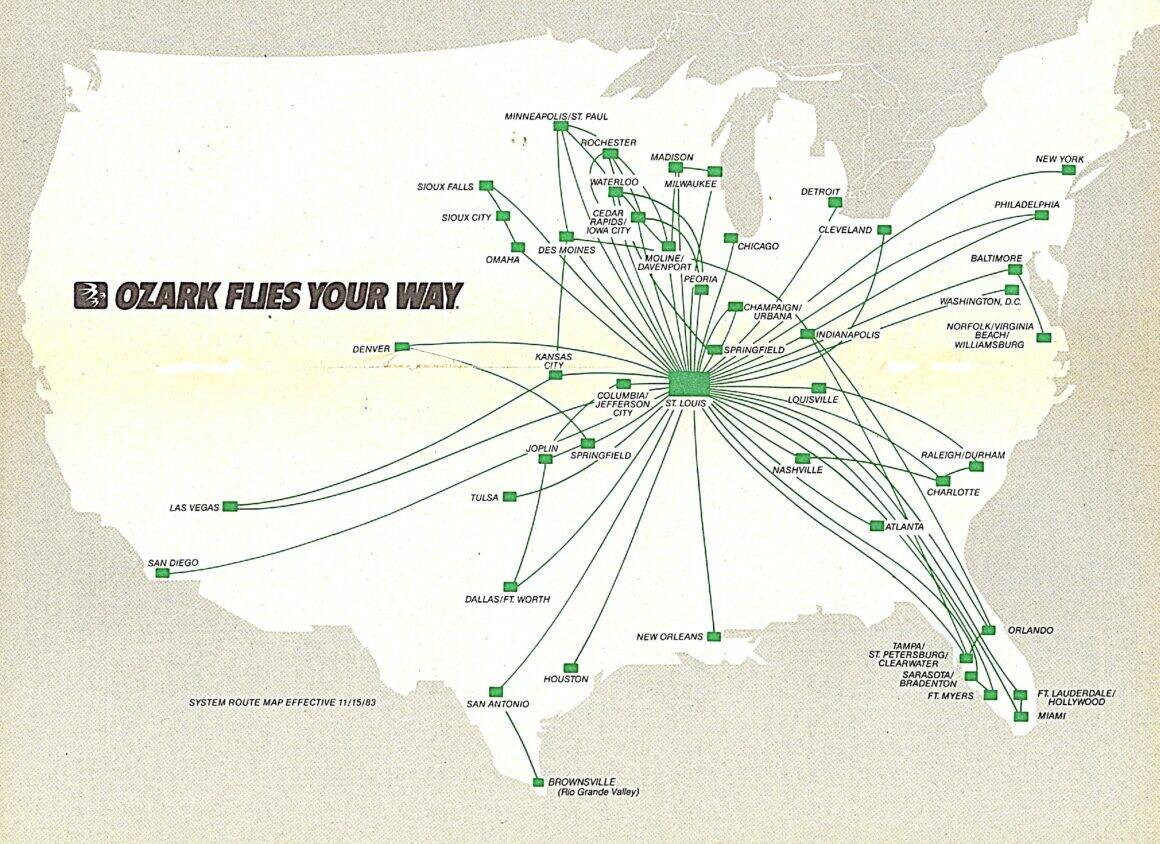

Initially, Ozark seemed to meet the challenges of deregulation by expanding in a conservative, yet methodical manner. Service was added from St. Louis to several Florida destinations, as well as to New Orleans and Houston.

However, the company then drastically changed its business model from a regional airline to a national competitor. Each new timetable issue introduced service to another station: San Antonio, Norfolk, Las Vegas, Cleveland, San Diego. Ozark management fell into the trap of fighting for the same passengers that every other major airline was fighting for, using the hub-and-spoke model. And they were doing it from their St. Louis hub, an airport that already had a formidable competitor – TWA.

152-passenger McDonnell Douglas MD-80s entered the fleet in 1984.

Sadly, on the other side of the coin, many of the smaller cities that Ozark had originally been formed to serve – Quincy, Bloomington, Sterling/Rock Falls, Galesburg, Mattoon/Charleston, Mt. Vernon, Marion/Herrin, Rockford, and Decatur, Illinois; Fort Leonard Wood, Kirksville, and Cape Girardeau, Missouri; Ottumwa, Clinton, Dubuque, Burlington, Mason City, and Fort Dodge Iowa; Paducah and Owensboro, Kentucky, and Clarksville, Tennessee/Hopkinsville, Kentucky – all eventually disappeared from the Ozark route map.

END OF THE LINE

In 1985, two things happened that would change everything for Ozark: Southwest Airlines, the low-cost carrier that did not follow the pack, entered the St. Louis market. Then, through a hostile takeover, Carl Icahn gained control of TWA. Icahn went to work reducing labor costs at TWA and reducing passenger fares, making it a more formidable competitor.

Ozark management had abandoned Ozark’s smaller stations and built the airline into a national player with routes radiating solely from St. Louis, which ultimately became the corner that the company had painted itself into. It had not grown big enough to withstand major players, and it was too late to change its game plan and become a low-fare point-to-point carrier like Southwest.

When Icahn made an offer to buy Ozark for $19 per share, he knew he had the upper hand. On 27 October 1986, Icahn merged Ozark with TWA. On that day, the eradication of Ozark began. Ozark Air Lines disappeared into Icahn’s TWA, an airline that would meet the same fate when it merged with American Airlines 15 years later.