Air Midwest Flight 5481 lasted just 37 seconds. This is what investigators uncovered and how the crash changed aviation safety.

On the crisp but calm morning of 08 January 2003, Air Midwest Flight 5481 was supposed to be a short, forgettable hop.

The Beechcraft 1900D was scheduled to fly from Charlotte Douglas International Airport (CLT) to Greenville–Spartanburg International Airport (GSP), a flight that typically took less than an hour and had been flown numerous times before.

Operating as a US Airways Express commuter flight, Flight 5481 was carrying 19 passengers and two pilots. At the controls were Captain Catherine “Katie” Leslie, 25, and First Officer (FO) Jonathan Gibbs, 27. Leslie was the youngest captain at Air Midwest at the time, with more than 1,800 total flight hours, including over 1,100 hours as pilot-in-command (PIC) on the Beechcraft 1900D. Gibbs had logged more than 700 hours on the type. Both pilots were based at CLT.

The aircraft itself, registration N233YV, had been delivered new to Air Midwest in 1996. By early 2003, it had accumulated more than 15,000 flight hours. Nothing in the flight’s paperwork or preflight checks suggested that this morning would be any different from the many departures before it.

Passengers boarded, bags were loaded, and the crew completed their required weight and balance calculations. According to NTSB records, 23 checked bags were loaded, including two unusually heavy pieces of luggage. The ramp agent recalled telling the captain about the heavy bags, and the captain responded that the weight would be offset by the presence of a child on board.

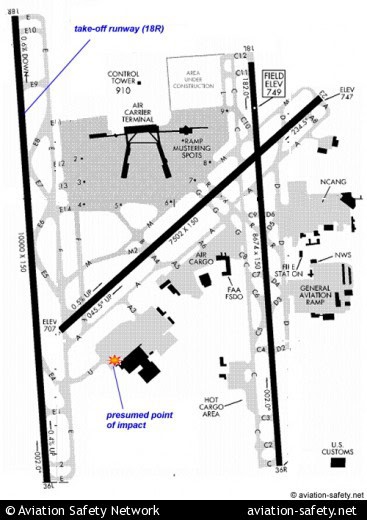

At approximately 0830 local time, Flight 5481 pushed back from the gate. Seven minutes later, it was cleared to taxi to Runway 18R. At 0846, the tower cleared the flight for takeoff.

Less than a minute later, everything unraveled.

A Fight for Control After Liftoff

As the Beechcraft accelerated down Runway 18R, nothing appeared abnormal. The takeoff roll was routine. But immediately after becoming airborne, the aircraft’s nose began pitching sharply upward.

By the time Flight 5481 reached about 90 feet above ground level, its pitch attitude had increased to 20 degrees nose up. Both pilots pushed forward on the control column, attempting to lower the nose. The airplane did not respond as expected.

Instead, the pitch continued to increase. Within seconds, the aircraft reached a dangerous 54-degree nose-up angle, activating the stall warning horn in the cockpit. Captain Leslie declared an emergency over the radio.

“We have an emergency for Air Midwest 5481,” Leslie told ATC as she and Gibbs fought for control of the airplane.

Flight data recorder information shows that the airplane climbed to approximately 1,150 feet above ground level before stalling. With insufficient airspeed and no effective pitch control, the aircraft rolled and pitched downward into an uncontrollable descent.

About 37 seconds after takeoff, at approximately 0847, Flight 5481 crashed into a US Airways maintenance hangar on airport property. The impact and post-crash fire destroyed the aircraft.

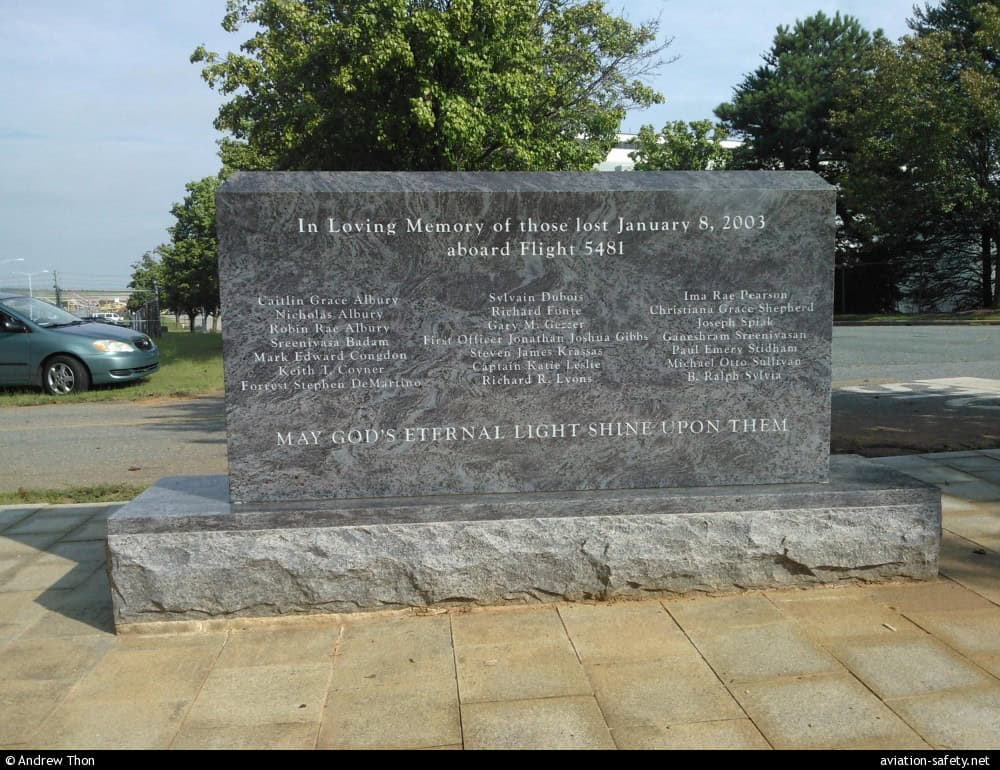

All 21 people on board were killed. One US Airways mechanic on the ground was treated for smoke inhalation. Miraculously, no one else on the ground was killed or injured.

The immediate question for investigators was painfully clear. How could a modern turboprop, flown by experienced pilots in good weather, become uncontrollable seconds after takeoff?

Two Hidden Failures

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) would ultimately determine that the crash of Flight 5481 was caused by a lethal combination of two separate failures. Either one alone might have been survivable. Together, they were catastrophic.

The first problem was weight and balance.

Although the flight crew calculated the aircraft’s takeoff weight as being within limits, those calculations were based on FAA-approved average passenger weights that were badly outdated. The NTSB later found that the actual average passenger weight exceeded the assumed values by more than 20 pounds.

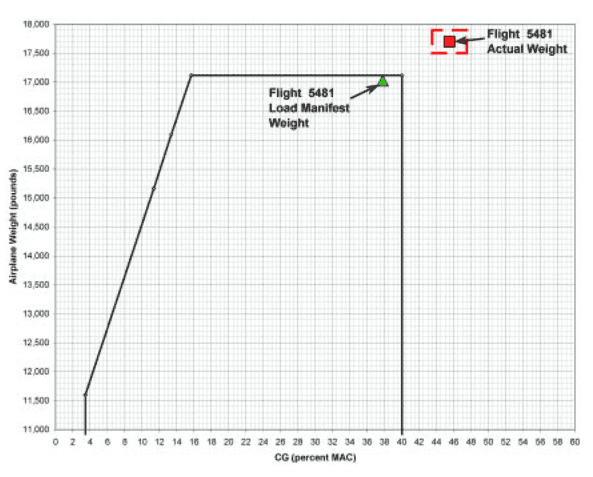

After accounting for the true weight of passengers and baggage, investigators determined that the aircraft was approximately 580 pounds above its maximum allowable takeoff weight. Even more critically, its center of gravity (CG) was about five percent beyond the aft limit. An aft CG makes an aircraft more pitch sensitive. It requires less control input to raise the nose and more force to push it down. That condition alone would have made the airplane harder to control, but not uncontrollable.

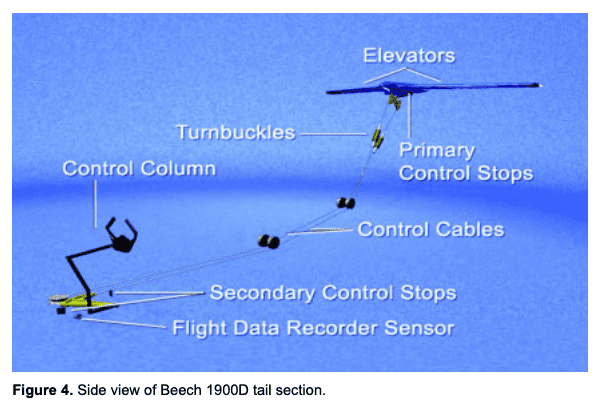

The second problem lay hidden in the tail.

Two nights before the crash, the aircraft underwent maintenance at Tri-State Airport (HTS) in Huntington, West Virginia. During that work, elevator control cable tension was adjusted. According to the investigation, the mechanic performing the task had no prior experience working on a Beechcraft 1900D.

The elevator cables were adjusted incorrectly. Turnbuckles were set in a way that severely limited elevator travel. As a result, the pilots did not have sufficient nose-down authority available when they needed it most.

Compounding the error, a required post-maintenance operational check was skipped. The same maintenance supervisor who was overseeing the work also served as the quality assurance inspector that night. With no independent review, the aircraft was returned to service with a critical flight control system improperly rigged.

The NTSB concluded that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was aware of serious deficiencies in training and oversight at the maintenance facility at HTS, but had failed to correct them.

Flight 5481 was overloaded, out of balance, and unable to generate enough nose-down elevator authority. It was doomed before it even left the ground.

Lessons from Tragedy: What Changed After Air Midwest Flight 5481

In the years following the crash, the legacy of Air Midwest Flight 5481 extended far beyond the wreckage at CLT that January morning. One of its most lasting impacts reshaped how airlines think about a fundamental aspect of flight safety: weight.

At the time of the accident, standard passenger and baggage weights used for weight and balance calculations were based on FAA guidance that had not been meaningfully updated in decades. Those assumptions no longer reflected reality, particularly for small commuter aircraft, where even modest miscalculations could dramatically affect CG.

In May 2003, just months after the crash, the Federal Aviation Administration revised its standard weight assumptions for aircraft with 10 to 19 passenger seats. The new guidance increased the assumed average passenger weight, including carry-on items, from 180 pounds to 190 pounds during summer operations, with an additional five pounds added for winter clothing.

Standard baggage weights were also increased by five pounds (from 25 to 30 lbs).

Although a 2005 FAA survey later showed that average passenger weights had dipped slightly below the revised 2003 standard, the guidance remained in place. One of the many lessons learned from Flight 5481 was that conservative assumptions were safer than outdated ones, especially for aircraft operating close to their performance limits.

The push for accuracy did not end there.

In May 2019, the FAA issued updated advisory guidance emphasizing that weight and balance calculations must accurately reflect current passenger and baggage weights. Rather than relying solely on nationwide averages, the agency encouraged operators to review and update their methods. For some airlines, that meant conducting passenger weight surveys. For others, particularly those flying smaller aircraft, it meant weighing baggage individually or using more precise distribution methods.

These changes have occasionally sparked intense public discussion, especially around the idea of weighing passengers before boarding. The FAA guidance makes clear that such measures are optional, not mandatory. They are tools available to operators when accuracy is critical, particularly for smaller aircraft where a few hundred pounds can significantly alter aircraft handling.

Today, it is common practice for many carriers operating small aircraft to obtain passenger weight. While major US airlines rely on average passenger weight assumptions, many small commuter and Part 135 operators use actual passenger weights for safety. These include carriers such as Cape Air, Mokulele Airlines, Southern Airways Express, Key Lime Air, Denver Air Connection, and remote Alaskan carriers such as Bering Air.

For operators flying aircraft like the Cessna 402 and Cessna 208 Caravan, weighing passengers and carry-on items is nothing unusual. With tight CG limits and little margin for payload error, especially in Alaska and island operations, the practice is viewed as common sense rather than an inconvenience. On light aircraft, a few extra pounds in the wrong place can make a noticeable difference.

“Your Losses Will Not Have Been Suffered in Vain”

Two years after the crash, on 06 May 2005, Air Midwest took the rare step of publicly acknowledging its role. At a memorial near Charlotte Douglas International Airport, Air Midwest President Greg Stephens addressed the victims’ families.

“Air Midwest and its maintenance provider, Vertex, acknowledge deficiencies, which, together with the wording of the aircraft maintenance manuals, contributed to this accident,” Stephens told the families. “We have taken substantial measures to prevent similar accidents and incidents in the future, so that your losses will not have been suffered in vain.”

Air Midwest would cease operations in 2008. But the accident’s influence continues to shape aviation safety. Flight 5481 served as a tragic wakeup call to the regional airline industry (and, really, the entire aviation industry as a whole) that safety is not defined by a single system or decision. It is built from thousands of small calculations, inspections, and assumptions made long before the wheels ever leave the runway.

When those margins are eroded, even slightly, the consequences can be irreversible.