On Sunday, 1 August 1943, 177 USAAF B-24 Liberators departed their bases near Benghazi, Libya and headed out over the Mediterranean Sea toward Romania. Their targets were the oil refineries near Ploesti. The operation was called TIDALWAVE.

That day would prove disastrous for the USAAF, and came to be known as ‘Black Sunday’.

Target Analysis

Early on in the Second World War, allied Intelligence revealed a highly significant fact concerning Axis war industry in Europe. Estimates determined that oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania supplied one-third of Germany’s oil and fuel requirements.

Within the first few months of the USA’s entry into the war, an attack on Ploesti had been proposed. This resulted in a small-scale raid against the refineries in June of 1942.

HALPRO and the First Ploesti Raid

The raid was flown from Egypt by B-24 crews of the Halverson Detachment, or as it was more commonly known, the Halverson Project (HALPRO).

Named after its commanding officer, Colonel Harry A. Halverson, HALPRO’s purpose was to send B-24 Liberators to Eastern China early in the war. From there, they were to bomb Japan. But when the Japanese captured their intended base, the whole thing was called off.

The bombers were already en route at the time, and had reached the Middle East. They were ordered to remain in the region, and ultimately formed the nucleus of the 376th Bombardment Group.

Combat Debut For the B-24 Liberator

A force of 13 HALPRO B-24 Liberators departed Fayid Egypt on 12 June 1942, headed for Ploesti. One ship apparently experienced some sort of difficulties and bombed the harbor at Constanta before turning away.

The remaining ships were able to hit the target, though weather affected navigation, and the bombing was not entirely accurate. Defenses were light, with some little flak and a few enemy fighters encountered.

Its mission complete, the force then headed for Habbaniyah, Iraq, per the plan. However, some ships, damaged or low on fuel, landed at alternate fields in Iraq and Syria. A total of 4 landed in neutral Turkey and were impounded, their crews interned. Three of the impounded ships are shown below.

The HALPRO raid against Ploesti saw the first use of the B-24 Liberator in combat by American forces. It was also the first heavy bomber operation flown by the USAAF in Europe.

‘Twas a proverbial pin-prick, and did little significant damage. The raid was considered a failure, and Army brass were not impressed. It didn’t seem that the ‘big bombers’ could play a significant part in winning the war.

But it was just the beginning. Just one operation. Failure or no, it proved that such operations were feasible, and likely to be more effective with a larger attacking force.

TIDALWAVE

The prospect of destroying the refineries at Ploesti came up again during the Casablanca Conference in January of 1943. Sufficient resources were unavailable at the time, however, and the idea was shelved for a short while.

Despite this, planning for another mission to Ploesti began as early as March of 1943, with the proposal of two different plans. A high-level attack by a medium-size force flying from bases in Syria, and a low-level attack by a larger force, flying from bases in Libya.

The latter plan was chosen for a number of reasons, among them the element of surprise. Fly low, avoid detection, get in quick, hit ’em hard, get out. TIDALWAVE would prove to be one of the most audacious USAAF operations of the war. And among the most costly.

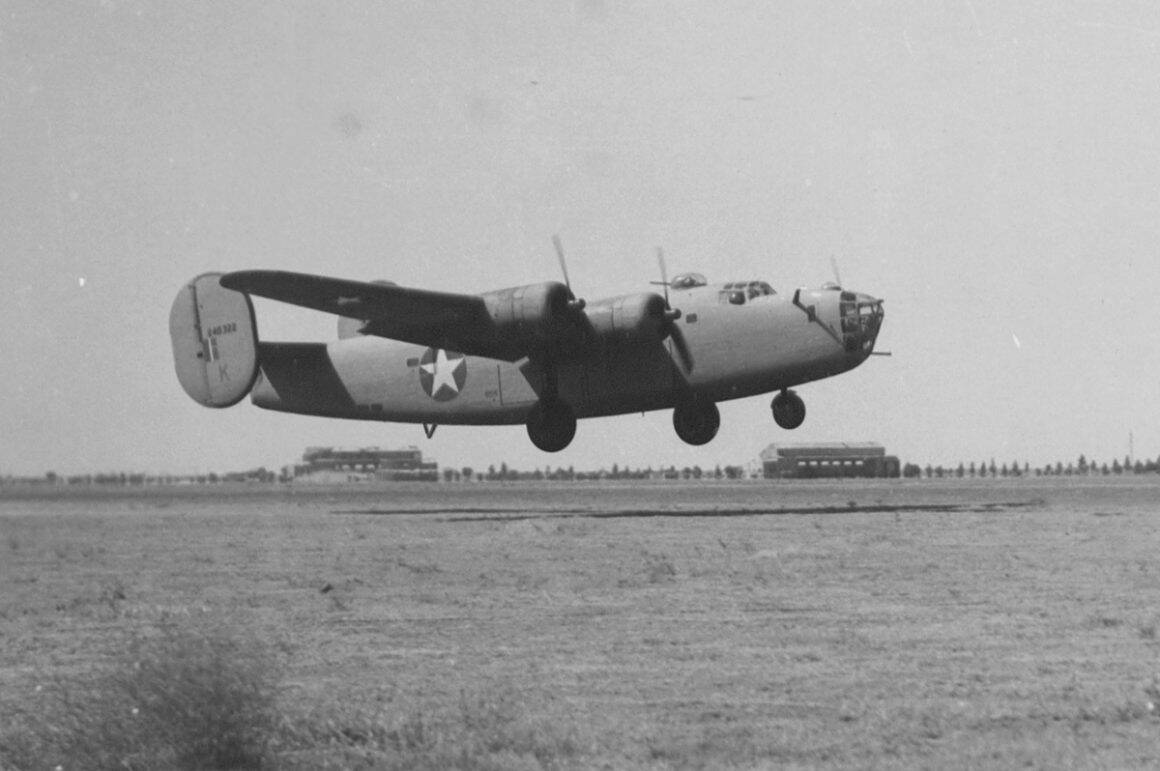

The B-24 Liberator Again Takes the Stage

At the time there were two heavy bombers in use by the USAAF: the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and the Consolidated B-24 Liberator.

The mission would be flown over a distance of roughly 2,100 miles. So the B-24 was chosen for its greater range, which could be extended by installing extra fuel tanks in the bomb bay.

The Ninth Air Force had two B-24 outfits in Libya: the 98th and 376th Bombardment Groups. Each was based near Benghazi, Libya which would be the starting point for the mission.

Those two groups wouldn’t be enough to do the job, however, so three more were borrowed from the Eighth Air Force in England. The 44th, 93rd, and 389th Bombardment Groups were given the task, and departed for Libya in June of 1943.

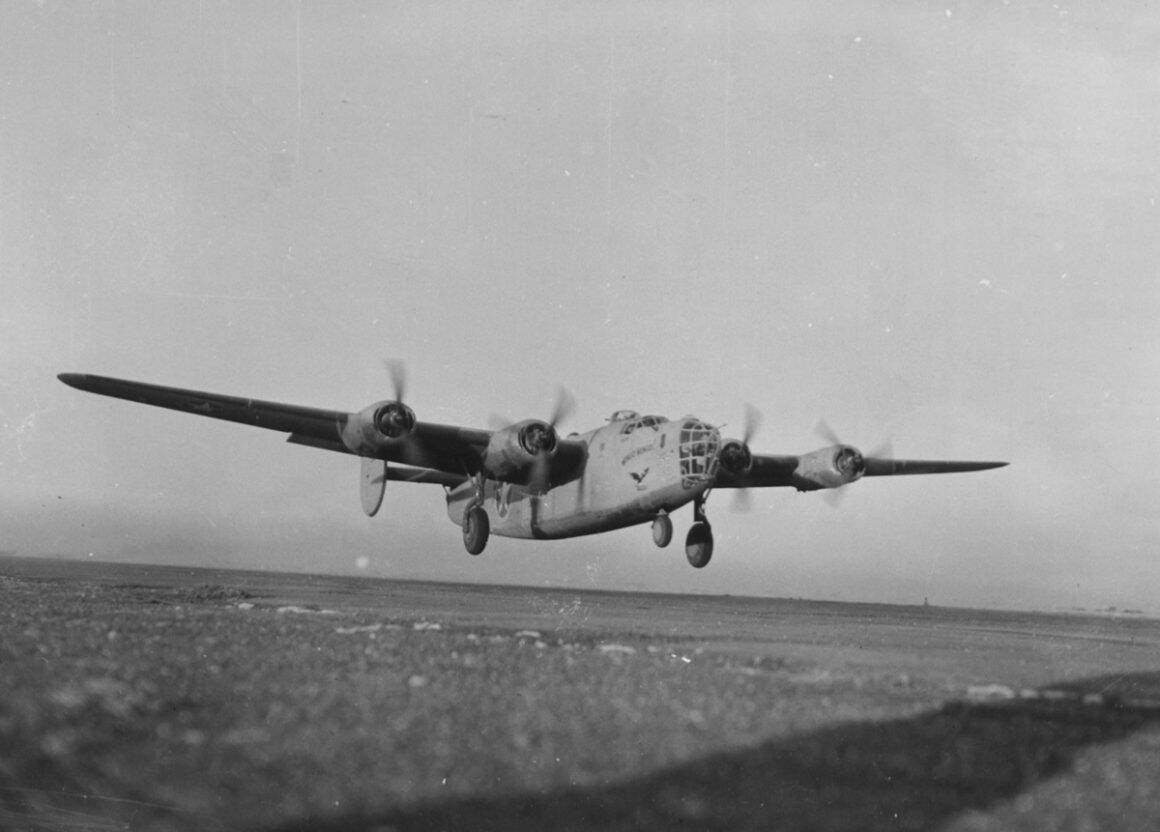

Crews were initially puzzled by orders that saw them flying low-level practice missions, which was highly unusual for heavy bombers. But full understanding soon came when the target and plan of attack were revealed.

The Plan

The B-24s would depart their bases in Libya and head north, crossing the Mediterranean and Ionian Seas. After passing the island of Corfu they would climb over the Pindus Mountains of southern Albania, continue across southern Yugoslavia, and into southwestern Romania.

Descending to very low level and turning east, they would head to a point northwest of Ploesti. From there, a final turn to the east, and the force would split up, heading toward individual targets at minimum altitude. Then home.

Timing and synchronization were key to the success of the mission. Radio silence would be strictly enforced. And maintaining cohesive formations, flying as one force, was vital.

The Mission – Off to a Bad Start

On the morning of the mission, several aircraft were ‘chalked in’, bringing force strength up to 178 aircraft. One Liberator was lost right off the bat when an engine failed and caught fire shortly after takeoff.

Another inexplicably fell into the sea during the trip across the Mediterranean. This ship, named ‘Wongo Wongo!’, flown by First Lieutenant Brian W. Flavelle of the 512th Bombardment Squadron, 376th Bombardment Group is shown below.

This loss had a grave impact on the entire mission. ‘Wongo Wongo!’ carried the lead navigator for the entire force, First Lieutenant Robert F. Wilson.

A ship that had descended to check for survivors almost collided with another B-24, fell behind, and was unable to regain formation. ‘Twas another blow to the mission, as this ship carried the force’s backup navigator.

Confusion ensued, and cohesion of the formation began to break down. Orders for strict radio silence prevented coordination in reassembling formation, compounding the problem.

More Misfortune

The island of Corfu came into sight, then the Albanian coast. Here, Mother Nature’s whim came into play. The Pindus Mountains were shrouded in cloud. Several aircraft, unable to regain formation after the crash of ‘Wongo Wongo!’, struggled to gain altitude and aborted.

The rest ascended to a safe altitude above the mountains. But the lead groups, the 376th and 93rd, had to throttle up considerably to do so, pulling far ahead of the others.

They had also caught a tailwind. And upon descending to 500 feet after crossing the Pindus, they found themselves barely within sight of the trailing groups.

The not-oft-seen photo below was taken from a B-24 Liberator of the 389th Bombardment Group while en route to Ploesti.

By the time the 376th and 93rd Groups reached Romania, they were roughly twenty minutes ahead of others. The plan had called for a one-minute spread across the entire force.

Navigational Error of the B-24 Liberators

The careful timing and synchronization so meticulously worked into the plan had been thrown off, and then some. Now, it would be thrown right outta the window.

Along the planned route running northeast, three cities, Pitesti, Targoviste,and Floresti served as checkpoints for the final turn toward Ploesti.

The 93rd and 376th Groups turned too early, however, at Targoviste, and headed toward Bucharest. The 44th, 98th, and 389th Groups continued on to make the turn at Floresti.

Some immediately recognized the error, and crews from both the 376th and 93rd broke radio silence, attempting to call attention to it. But their calls went unheeded for a time.

First, one ship from the 376th turned northeast toward Ploesti, soon followed by the entire 93rd Group. The rest of the 376th did the same a good while later, but wound up approaching Ploesti from the southeast.

First Blood

That lone Liberator from the 376th Group was the first B-24 to reach the target that day. Called ‘Brewery Wagon’ and flown by First Lieutenant John Palm, the ship approached the refineries and came under heavy ground fire.

The Liberator was hit badly, killing the navigator, Second Lieutenant William K. Wright, and bombardier, Second Lieutenant Robert W. Merrell. Palm was determined to drop his bombs on a worthy target, “come hell or high-water”, he later said.

But Hauptmann Wilhelm Steinmann of JG 4 was patrolling the area in a Messerschmitt Bf 109, and caught sight of the stricken Liberator. He attacked, finishing the bomber off. Palm was wounded, losing a leg. But his co-pilot, Second Lieutenant William F. Love, was able to set the ship down in a field.

Though Wright and Merrell were killed, Palm, Love, and the rest of the crew survived and were taken prisoner. Here’s a photo showing ‘Brewery Wagon’ at Benghazi on the morning of the raid.

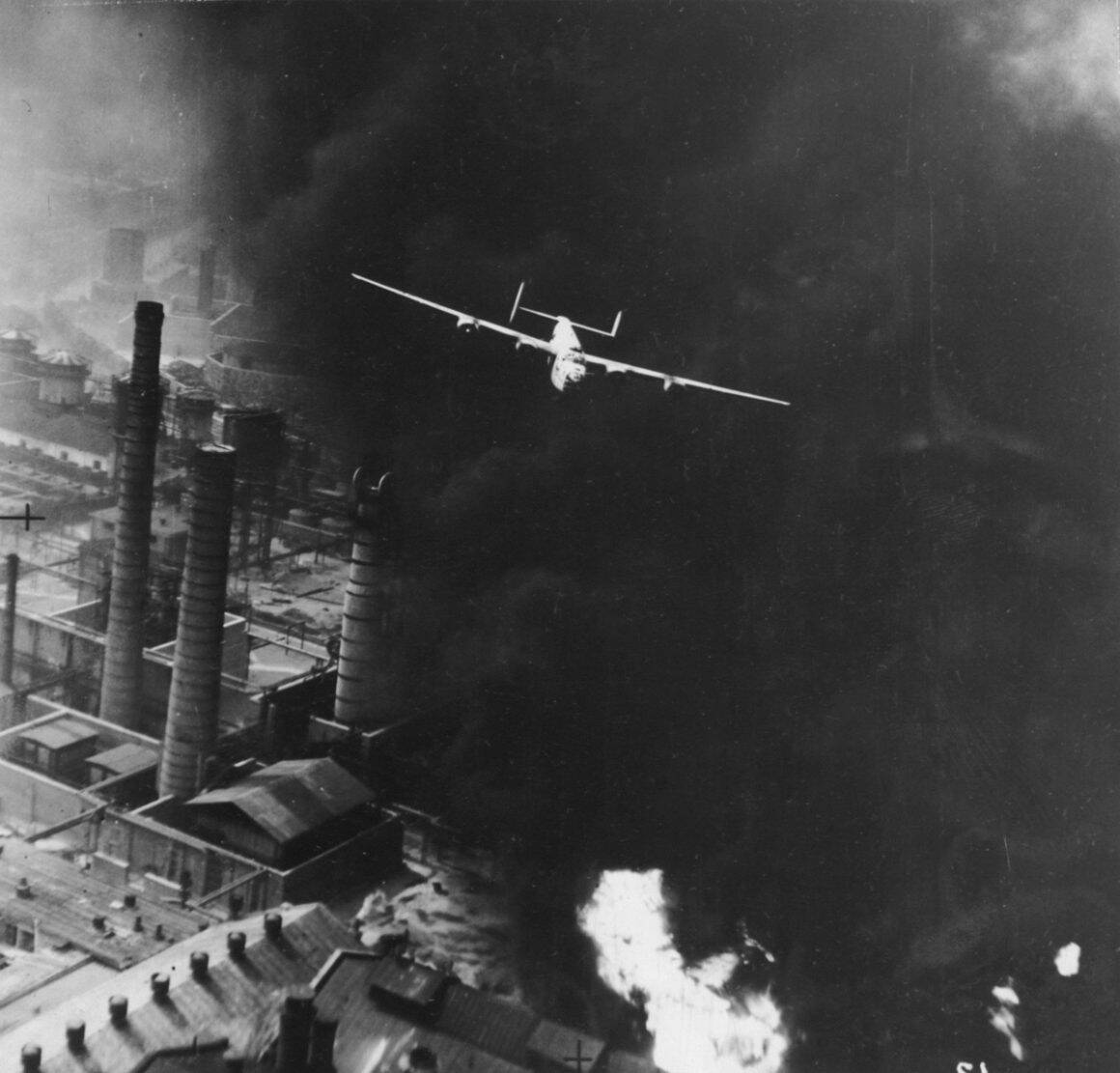

B-24 Liberators Fly Straight Into Hell

The 93rd and 376th ships approaching from the south mostly wound up attacking targets of opportunity, then turning to the southwest to head home. They had taken heavy losses from the innumerable defending flak positions.

As the 44th, 98th, and 389th Groups approached their specific targets as planned, they found them already burning. Some searched for alternate targets, but many drove straight into the inferno and bombed their assigned targets as best they could.

Enemy defensive fire was not the only hazard. The thick black smoke from burning oil, combined with the low altitude at which the bombers were flying, produced a recipe for disaster.

Collision with barrage balloon cables and tall ground structures such as smoke stacks was almost inevitable. Their own bombs also presented a danger, especially when a ship would pass over a delayed detonation.

Aircraft were crisscrossing all over the place, trying to avoid these obstacles as well as other maneuvering B-24s. There were accounts of ships flying into billowing black clouds, failing to emerge on the other side.

Others described choking, acrid smoke permeating the interiors of the planes, and how men were roasted by the intense heat. Almost quite literally.

Eyebrows, mustaches, and five o’clock shadow were all singed. Exposed skin was burned red by the heat, which reached upwards of 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

Again, heavy losses were suffered, both to the enemy and to misfortune.

Remaining B-24 Liberators Heading Home

All the surviving Liberators would turn southwest after their bomb runs and attempt to escape the area. There were many small groups of two or three aircraft, and many others went it alone.

Flak positions continued to hammer away at the fleeing B-24s, as did fighters, both German and Romanian. Numerous losses were suffered on the return trip, some as far out as the Ionian Sea, where five Liberators were downed by Bf 109s of JG 27.

Even a number of Bulgaria’s Avia B.534s got into the tussle, scoring hits but no victories. Their rifle-caliber guns didn’t pack enough punch to knock down a B-24 Liberator.

Return to Libya, Seeking Refuge, and the Reckoning

Of the original force of 178 B-24s that took off from airfields around Benghazi, 88 returned. Some 55 of these were damaged to some extent, some quite heavily. Many would never fly again.

I’ve come across varying numbers as to aircraft losses, but it seems that 44-45 were lost to air defenses. A few others, such as ‘Wongo Wongo!’ were destroyed under other circumstances.

The rest made for friendly bases such as Cyprus, or came down in neutral Turkey (7 aircraft) where crews faced internment.

Aircrew losses were 310 killed, 108 captured, and 78 interned in Turkey. Apparently 4 others were taken in by Tito’s partisans in Yugoslavia.

Accolades

Among the awards given to participants of this raid were 56 Distinguished Service Crosses and 41 Silver Stars.

The Medal of Honor was awarded to five men:

Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker (posthumous)

Major John Jerstad (posthumous)

Lieutenant Lloyd Hughes (posthumous)

Colonel Leon Johnson

Colonel John ‘Killer’ Kane

There could easily have been more.

What Did TIDALWAVE Accomplish?

The results of the raid saw a 40% decrease in Romanian oil production, but this was largely restored within months. And apparently there was an overall increase in production.

This was understated in a subsequent appraisal of the raid’s effectiveness, which concluded that there was “no curtailment of overall product output”.

Repairs to the refineries went relatively quickly and without interruption. Largely because of the grievous losses suffered by the attacking force. So many aircraft were lost or put out of commission, that any sort of immediate follow up attacks were out of the question.

So, despite what allied newsreels may have indicated, the operation was deemed a failure. A failure that served to help strengthen Allied resolve in destroying Axis oil production.

Perhaps most importantly, lessons were learned. The USAAF never again attempted such an audacious low-level raid with heavy bombers in Europe.

More attacks on the refineries at Ploesti were made by the heavies, beginning in April of 1944. But this time, the B-24 Liberators, and B-17 Flying Fortresses were sent in to do the job the way they knew best. Dropping alotta things that go boom, all in one spot, and from high up.