Turning to Kenney’s In-House Genius

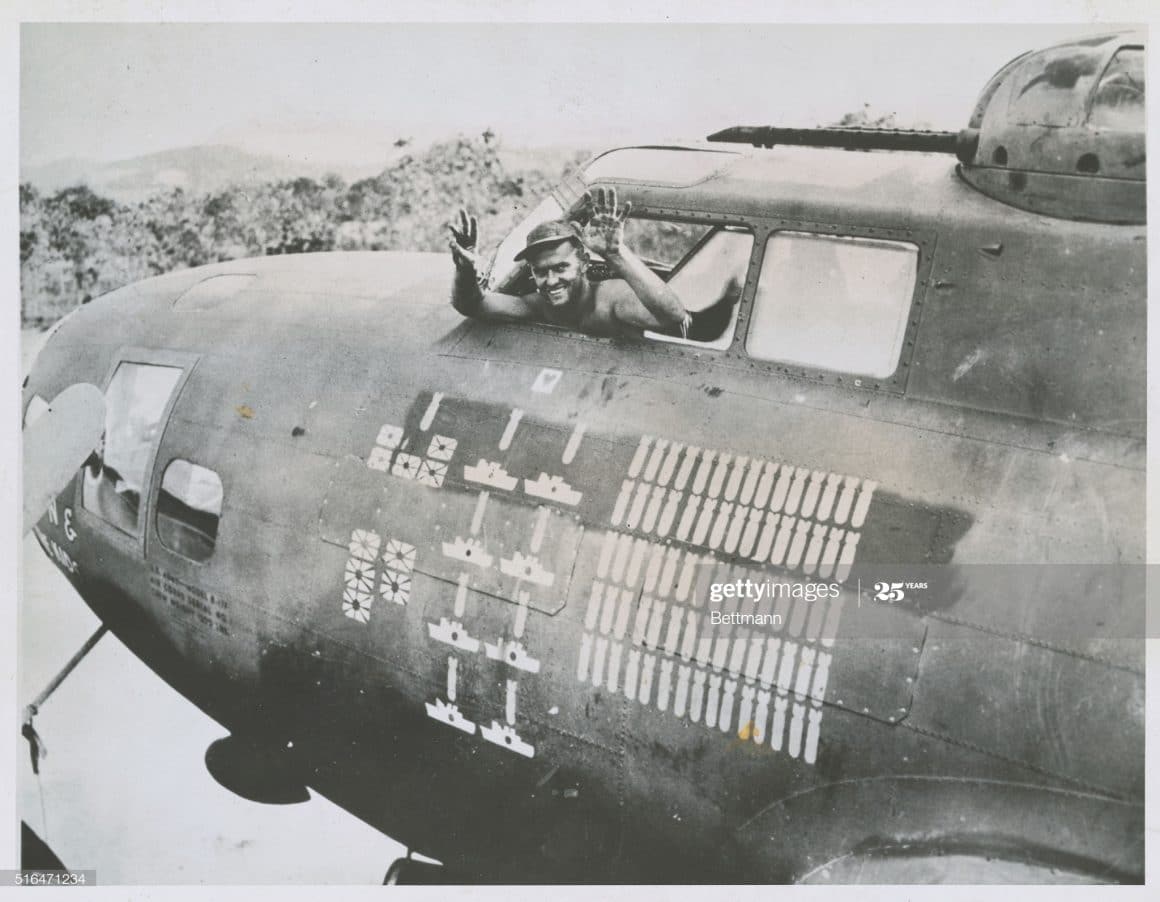

The USAAC had been modifying existing airframes with the intention of creating medium bombers General Kenney liked to call “commerce destroyers.” Kenney’s weaponeering genius, Major Paul “Pappy” Gunn, had stuffed four .50 caliber machine guns in the noses and extra fuel tanks in the bomb bays of some A-20 Havocs in late 1942. Thinking that the B-25 Mitchell bomber would also make an excellent “commerce destroyer”, Gunn tried the same thing with the B-25 but ran into some technical problems that he would later overcome.

Skipping and Bouncing Bombs

Another innovative new tactic that would be attempted for the first time in the Pacific was skip bombing. The British and Germans had been using skip bombing for some time. When the RAAF demonstrated the basics of skip bombing and masthead bombing, both low-level attacks that attempted to put a bomb into the side of the target rather than through the deck, The USAAC pilots bought right in. Even a miss could heavily damage a ship if the bomb exploded under the ship (in all likelihood breaking her back) or over the ship (raking the decks with shrapnel and starting fires). The machine guns in the attacking bombers’ noses would cause serious damage to equipment and personnel on the ship even if the bombing attack was unsuccessful. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea would be the Pacific debut of the gun-nosed strafing skip bomber.

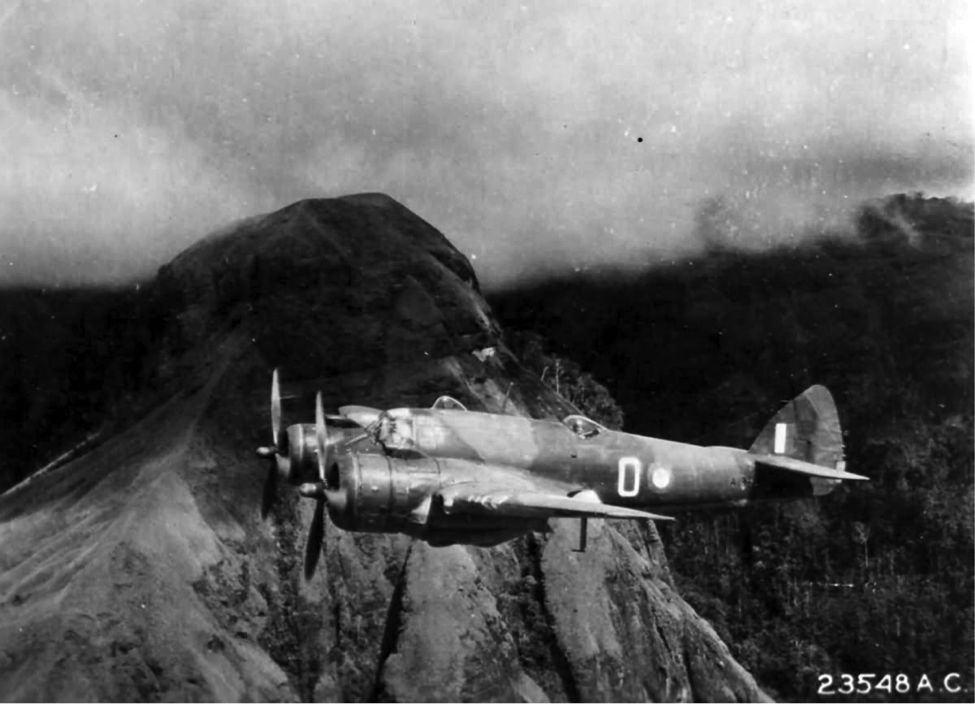

The Beautiful Beaufighter

The RAAF Beaufighters in the area were ready-made commerce destroyers in their own right. Equipped with four 20 millimeter cannons and six wing-mounted .303 caliber machine guns and capable of attacking with both bombs and torpedoes, the Beaufighter was one of the Allies’ best platforms for anti-shipping attacks.

Throwing Everything the Allies Had at the Enemy

The Allied order of battle shaped up with RAAF Hudsons, Beaufighters, Beauforts, and P-40 Kittyhawks of 71 and 73 Wings Royal Australian Air Force all tasked against the convoy. USAAC A-20 Havocs, B-25 Mitchells, B-17 Flying Fortresses, B-24 Liberators of the 38th, 43rd, and 90th Bombardment Groups, P-39 and P-400 Airacobras, P-40 Warhawks, and P-38 Lightnings of the 35th and 49th Fighter Groups, and the 3rd Attack Group made up the American forces. Totaling just shy of 200 aircraft, these combined Allied forces would have to contend with about 100 Japanese fighter aircraft tasked with covering the convoy.

Japanese Order of Battle

Operating under the code name designation Operation 81, the convoy consisted of the Japanese destroyers Arashio, Asashio, Asagumo, Shikinami, Shirayuki, Tokitsukaze, Urinami, and Yukikaze, which carried a total of 958 troops bound for New Guinea. The Army transports Aiyo Maru (2,715 tons), Kembu Maru (950 tons), Kyokusei Maru (5,493 tons), Oigawa Maru (6,494 tons), Sin-ai Maru (3,792 tons), Taimei Maru (2,883 tons), Teiyo Maru (6,870 tons), and the Navy transport Nojima Maru (8,125 tons) carried the remaining 5,956 troops.

Standing Out into a Stormy Sea

The Japanese ships departed Simpson Harbor on Rabaul on 28 February. The ships were able to take advantage of stormy conditions in the area until 1 March, when they were sighted by a searching B-24 Liberator. But B-17s sent to the reported location failed to sight the convoy.

Medium-Altitude Level Bombing Successes

At dawn the next day, 2 March 1943, another Liberator sighted the Japanese convoy. The first to attack were 28 B-17s. Attacking with 1,000 pound bombs from 5,000 feet, the B-17s sank the Kyokusei Maru and damaged Nojima Maru and Teiyo Maru in one of the few examples of successful level bombing against shipping up to that point in the war. That evening 11 more B-17s attacked the convoy again and damaged one more transport. RAAF PBY Catalina flying boats shadowed the convoy overnight.