“Any normal person can handle an airplane,” said the owner of what would become American Airlines. Unions formed to counter safety issues and poor working conditions.

The early history of the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) union is singularly identified with David Behncke. Born on a farm in Wisconsin to immigrant German parents in 1897, Behncke joined the Army in 1916 and would get his pilot wings and a commission as a second lieutenant in 1917. Following his Army service, he flew around the Midwest and Great Lakes region in the 1920s with his own barnstorming outfit and participating in air races.

To supplement his income, he made a bit of a local name for himself in Illinois, flying custom-tailored suits from Chicago to various cities. This work brought him to the attention of Minneapolis businessman Charles Dickenson, who had just secured an air mail contract between Minneapolis and Chicago.

In 1926, Behncke became the first pilot for Dickenson Airlines on Air Mail Route 9. However, the struggling airline soon faced the loss of its contract. A group of businessmen from Detroit and Minneapolis, led by Lewis H. Brittin, acquired the airline and rebranded it as Northwest Airways—the forerunner of Northwest Airlines. Northwest moved into passenger transport like many of the air mail carriers of the day, and it was David Behncke who flew Northwest’s first passengers on 1 February 1927.

An airline pilot’s fortunes in those days often waxed and waned at the whim of the airline owners. Before long, Behncke changed jobs and, by 1928, was flying for Boeing Air Transport out of Chicago, which later became United Airlines. It was during this transition period that Behncke began contemplating organizing airline pilots into a union that wouldn’t be limited to one airline but encompass pilots from other airlines as well.

Flying professionally in the 1920s was still a hazardous job. For many airlines, the attitude of the owners was typical for the 1920s, which espoused an accumulation of wealth with little regard for the workers. For the airlines of the day, this meant the pilots were often low-paid on top of what was already considered a hazardous job. Two main factors led Behncke to move forward with his plans for a pilots’ union.

The first one was, of course, the “robber baron” attitudes of the day. Even though the number of passengers was increasing, the air mail contracts were lucrative, and the US Post Office paid airlines by the pound. It wasn’t unusual in those days for airlines to mail heavy, useless items to pad their bill and get more from the Post Office. Many individuals who ran airlines became quite wealthy as a consequence, and for an average low-paid pilot who routinely saw the sorts of things done to boost air mail profits, it was unsettling.

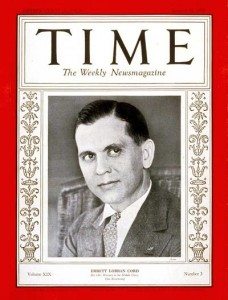

Many of the pilots of the day served in the First World War and were rightly proud of their service and felt that what was going on in those days was contrary to how they ended up with their pilots’ wings. The industrialist E.L. Cord, who was an early owner of what became American Airlines, for instance, wasn’t shy about stating his low regard for the pilots of the airlines he owned. “Any normal person can handle an airplane,” he declared in 1930.

The second factor was the practice of pilot pushing. Even with the carriage of passengers, there was tremendous pressure on pilots to fly with poorly repaired aircraft or in unsafe weather conditions. Many airlines offered financial incentives to pilots who would take a flight that had been turned down by a fellow pilot. With the Depression underway, there were plenty of out-of-work pilots to replace pilots who refused to fly for safety or weather reasons.

In the 1920s, there was a social organization of pilots called the National Air Pilots Association, NAPA. In 1928, while still working for what became United Airlines, Behncke was elected to a high position in NAPA. He urged the organization to take a vocal stand against pilot pushing by adopting the slogan “Don’t overfly a brother pilot!“ Unfortunately, only a small fraction of NAPA’s members were professional pilots, and Behncke’s proposals fell on deaf ears.

Behncke felt the financial incentives to fly in unsafe conditions were the worst evil of the profession. In fact, in 1928, most air mail pilots only had about a 25% chance of surviving several years flying the line. For many airline owners, the loss of an aircraft and a pilot was an easy cost to absorb, given the lucrative air mail rates of the day.

Behncke decided he had to form a union on his own, and by early 1931, word was out what Behncke was up to. Many of the airline heads who would later have formative roles in the US airline and commercial aircraft industry were quite intense in their anti-union opinions. The iconic head of United Airlines, for example, Pat Patterson, quite openly declared that “Nobody can belong to a union and fly for United!“. Gathering 24 trusted fellow pilots from other airlines, Behncke and the so-called “Key Men” met at the Morrison Hotel in Chicago on 27 July 1931 to form the Air Line Pilots Association, ALPA.

Because of the intense dislike of their activities by their respective employers, the “Key Men” were referred to by letter codes in an attempt to hide their roles from their employers. Bryon Warner of United, for example, was known as “Mr. A”.

While that date is considered the birth of ALPA, a year prior, Behncke did meet with a closed inner circle from three different airlines to set the wheels in motion for the 1931 meeting. They were Walter Hallgren and Lawrence Harris from American, R. Lee Smith of Northwest, J.L. Brandon of United, and another United pilot whose name is lost to history as he had switched to management not long after the 1930 meeting- the so-called “Lost Founder” of ALPA.

As membership of ALPA grew in that first year, Behncke had to move the operation out of his home and into a two-room suite at a Chicago hotel. Many pilots were tired of how they were treated at their respective airlines, but many airline managers were quite open in their threats to fire anyone joining ALPA. Many of the “Key Men” from the 1931 meeting did end up losing their jobs. And if the airline didn’t fire you for joining ALPA, they certainly did what they could to make you miserable.

TWA, for example, often shuttled pilots among different crew bases at short notice in an effort to make their families’ lives difficult as well. Schedules were often used punitively against anyone even suspected of ALPA membership. Many pilots who weren’t fired found themselves demoted from airliners to open-cockpit biplanes flying mail at night. Many airline managers felt they needed to stamp out ALPA quickly before it gained momentum. Eddie Rickenbacker of Eastern Air Lines, in particular, became a lifelong foe of the union.

In 1932, Behncke was working on getting ALPA affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) when a strike at a small airline thrust him and ALPA into the national spotlight. E.L. Cord was an aggressive businessman who, in a few short years via acquisition, headed an impressive industrial and transportation conglomerate that started with automakers of the day, given his background as an auto salesman for Auburn Auto.

In fact, Auburn Auto was one of his first acquisitions in 1924, turning the company around to the point it was introducing several new models a year, but this was accomplished by a ruthless attack on labor costs that would set the pattern of his business dealings in future corporate acquisitions. In short order, he acquired Dusenburg Automobiles as well as both Yellow Cab and Checker Cab.

He then moved into aviation, acquiring Stinson Aircraft (he was a private pilot who owned a Stinson Detroiter) and Lycoming Engines. Cord owned Stinson Aircraft when the company produced the Stinson Trimotor. It competed for airline orders with the Ford Trimotor, which cost $40,000. Cord’s eye towards draconian labor cost cuts meant he could offer the Stinson Trimotor for only $25,000.

In 1930, he decided to enter the airline business, seeing the profit potential with air mail subsidies. He started Century Airlines, which began flying in March 1931 with three daily round-trip flights between Chicago and St. Louis via Springfield and three daily round-trip flights between Chicago and Cleveland via Toledo. And quite naturally, Century Airlines flew Stinson Trimotors. He then set up other similar airlines around the nation, all with “Century” as part of their name.

In addition, he acquired other smaller carriers, like a small Texas-based outfit called American Airways. Lacking a lucrative air mail contract, Cord cut costs as far down as he could, reasoning that if he could operate his airlines at half the cost of the established airlines, air mail contracts those airlines had would be canceled and given to him.

With lower costs already, he stood to make a significant profit as a result. He had figured out he could pay pilots as little as $150/month at his Century Pacific operation between San Francisco and Los Angeles and still find pilots willing to work for him. Century Airlines, based in Chicago, had higher-paid pilots at $350/month, which was still quite a bit lower than the industry standard of the day. Since he was getting away with only $150/month with Century Pacific, Cord cut the salaries of the 25 pilots working at Century Airlines to $150.

The chief pilot at Century, Duke Skonning, called the rates “starvation wages” and wanted to bargain with Cord. Cord agreed to a 10-day period before instituting the new wage cut, but he had no intention of bargaining with the pilots who had already been disregarded. At the end of the 10-day period, as each Century flight arrived at Chicago Midway (called Chicago Municipal back then), each pilot was escorted off the plane by Cord’s guards and made to sign a new agreement for $150/month.

Every single pilot refused, setting off the first strike in the airline industry. Now locked out, those pilots showed up at Behncke’s door, led by their chief pilot, Duke Skonning, who told Behncke, “Well, here we are. We have been locked out. What is the Association going to do about it?“

Behncke’s work to get affiliated with the AFL paid off quickly. Immediately, the AFL had its Chicago chapter work with ALPA and the striking pilots. Behncke asked each ALPA member at other airlines to chip in $25 to help pay the bills of the striking Century pilots. Soon, radio spots were airing throughout Chicago to bring attention to the Century strike.

Cord quickly hired strikebreakers, but before they could show up for work, ALPA members would meet with them to explain what was at stake. Most still went to work with Cord, but some stayed with ALPA with the promise of help finding a non-strikebreaking flying job. This infuriated Cord, who then sequestered his new hires under armed guard at the airport.

This, in turn, angered the City Council of Chicago, which didn’t like Cord treating city property as a prison. He was subpoenaed to appear before the council, but Cord snubbed them, further hurting his cause. The AFL made sure Congress knew of Cord’s actions, and this was how ALPA gained its first political ally- Representative Fiorello La Guardia from New York emerged to champion ALPA’s cause in Congress.

It spawned a friendship between David Behncke and La Guardia that lasted long after La Guardia became mayor of New York City. With congressional pressure on him, Cord sent a letter to each member of Congress referring to ALPA and the Century pilots on strike as communists- since most pilots had military backgrounds, this backfired on Cord and set many Congressional officials against him to side with ALPA.

Cord’s luck was running out fast, and in 1932, he gave up control (but not ownership) of his airline ventures. They were all folded into a holding company and, in short order, a few years later, rebranded as American Airlines. Cord dispatched one of his young executives to Texas to run the airline for him- an accountant named C. R. Smith, who would come to lead American Airlines until 1968. Putting Smith in charge was one of his concessions to Congress to avoid getting American’s air mail contracts canceled as a penalty.

By 1936, Behncke found pilot jobs for all of the striking pilots from Century Airlines. He also made sure all the strikebreakers at Century were exposed. In an editorial, Behncke first used the term “scab” to refer to airline labor practices. Many of those strikebreaking pilots found it difficult to find jobs in the industry. Behncke agreed to take them into ALPA for assistance in finding work, provided each striking pilot from Century Airlines found work first.

The Century Airlines strike gave ALPA national recognition, which wouldn’t have been possible without the AFL’s help and Fiorello La Guardia’s friendship. But with a newfound stature and friends in all the right places, many airlines that only a few years earlier tried to stamp out ALPA quietly acquiesced to its presence among its pilot ranks.

Sources: Flying the Line: The First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association by George E. Hopkins. The Air Line Pilots Association Press, 1982, pp 10-53. The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame http://www.wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org/.