From the Boeing 707 to the Ilyushin Il-62, early long-range jet airliners transformed how the world traveled across oceans.

During the late 1950s, as the world’s major aircraft manufacturers transitioned into the jet age, early long-range jet airliners emerged as successors to piston-driven types, such as the Douglas DC-7. These swept-wing, four-engine narrow-body designs laid the foundation for modern intercontinental air travel.

The United States and the Boeing 707 / Douglas DC-8 Rivalry

In the United States, Boeing and Douglas quickly became dominant forces in the development of early long-range jet airliners, with the 707 and DC-8 defining the template for intercontinental jet travel.

Long before the 707, Boeing designed the B-247, which could be seen as the first “modern” airliner. It had an all-metal, cantilever, low-wing configuration; cowling-encased engines; and retractable landing gear. During the piston days, Boeing mostly took a back seat to Douglas. It produced the B-307 Stratoliner (the first pressurized airliner), the B-314 Flying Boat, and the B-377 Stratocruiser. The B-377 included a staircase-accessed lower-deck bar and lounge.

During the pure-jet era, the Boeing-Douglas duopoly imbalance shifted. The 367-80 served as the prototype for both the KC-135 military Stratotanker and the 707 airliner. With sleek lines, swept wings, podded engines, and a conventional tail, it influenced many early four-engine, narrow-body jets. It was made in four main versions.

The first, the 707-120, was powered by four 11,200-pound-thrust Pratt and Whitney JT3C-6 turbojets and accommodated up to 179 passengers. It had a mixed-payload range of 3,300 nautical miles, but, as the initial version, it was not really a “long-range” jet.

The second variant, the 707-220, used four 15,800-pound-thrust JT4A-3 engines. It was designed for high elevation and temperature, serving airports that require more performance. Only five were built for Braniff International’s South American routes.

The 707-320, the third version, was the first true “long-range” model, boasting a 4,155 nautical-mile full-payload capability. However, a mixed-class arrangement increased this to 5,180 miles.

Equipped with four Pratt & Whitney JT4A turbojets, the 707-320 featured a stretched fuselage that accommodated up to 189 passengers and a re-engineered wing with increased span and area, thereby boosting lift and range.

The fourth major version, the 707-420, featured 17,500 thrust-pound Rolls-Royce Conway aft-fan engines and had a payload-varying range of between 4,225 and 5,270 miles.

The 707-320B, with 18,000 thrust-pound JT3D-3 engines, introduced low-bypass-ratio turbofans, as opposed to the previous “straight-pipe” ones, and was therefore quieter. It had a range of up to 5,385 miles.

Further down the West Coast, in California, the DC-8 marked Douglas’s transition to the jet age, following its highly successful piston series from the DC-1 to the DC-7.

Among early long-range jet airliners, the Douglas DC-8 distinguished itself with exceptional range growth and flexibility across multiple variants.

The DC-8 was built without a prototype and had a fuselage wide enough for six-abreast coach seating, which pushed Boeing to widen its 707 to compete. Several versions often matched Boeing’s design.

Powered by four 17,500-pound thrust JT4A-11 or -12 turbojets and introducing a new, chord-increasing wing leading edge, the DC-8-30 Intercontinental was the 707-320’s counterpart and offered transatlantic range to launch operators Pan American and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines.

The DC-8-40, the 707-420’s equivalent, introduced 17,500 thrust-pound Rolls-Royce Conway engines and a 315,000-pound gross weight, and the DC-8-50 was the first turbofan variant with JT3D-1s, giving it a full-payload, 6,000-mile range.

All these aircraft seated 189 in a six-abreast, single-class configuration, but the DC-8-61, with a 36.8-foot longer fuselage, took maximum capacity to 259 and was, for a time, the world’s largest commercial airliner.

The DC-8-63, with the same length but 19,000 thrust-pound JT3D-7 turbofans housed in revised, pencil-thin nacelles, had a 4,500-mile range.

The DC-8-62 retained its powerplants but featured a modest 6.8-foot fuselage stretch. It could seat 200 passengers and had three-foot, drag-reducing wingtip extensions. It became the world’s longest-range commercial airliner until the Boeing 747SP was introduced. The full payload range was 5,214 miles, enabling nonstop flights from the US West Coast to Europe.

In total, 556 DC-8s of all variants were produced.

Britain’s Quest for Long-Range Jet Performance

Although the de Havilland DH.106 Comet will be forever known as the world’s first pure-jet commercial airliner, turbojet availability, fuel capacity, and, to a degree, a lack of experience, reduced it to a medium-range aircraft at best, requiring British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) to serve Johannesburg, South Africa, from London with five en route refueling stops.

The Comet 1A added 1,000 Imperial gallons of fuel and increased passenger capacity from 36 to 44. The Comet 2 offered a three-foot fuselage stretch and 65,000 thrust-pound Rolls-Royce RA7 Avon 502 engines. Still, neither succeeded in placing the aircraft in the “long-range” category.

The first transatlantic version, the Comet 3, had an 18.6-foot longer fuselage, pinon tanks for 1,000 extra Imperial gallons of fuel, and 78 single-class passengers. It never entered production. In-flight explosions of earlier versions needed investigation first.

The Comet 4 series later offered greater range. BOAC operated the world’s first transatlantic London-to-New York jet flight on 4 October 1958, three weeks before Pan Am’s 707-120. However, it still required a refueling stop in Gander, Newfoundland (YQX).

Whether the definitive Comet 4C, which combined the Comet 4’s wing and fuel tankage with the Comet 4B’s longer fuselage for seating of just over 100, can be considered a true long-range aircraft is debatable, especially when compared to the Boeing 707-320B and the Douglas DC-8-50, DC-8-62, and DC-8-63.

More accurately classifiable as a “long-range” jetliner than the de Havilland Comet was the Vickers VC10. Although it was not originally conceptualized as a competitor to the two US quad-jets, it was designed instead to offer the performance that neither of them could.

Britain needed a pure-jet type to serve Commonwealth routes in Africa and Asia, which had hot, high-elevation airports and short runways. The design had to meet these tough conditions so BOAC could offer service.

The typical wing-mounted engine layout was unsuitable for demanding Commonwealth routes. Designers pursued maximum lift with a clean, 32-degree swept wing and advanced high-lift Fowler flaps. They concentrated four Rolls-Royce Conway turbofans at the extreme rear fuselage, and adopted a high T-tail to keep the horizontal stabilizer clear of engine exhaust.

The Standard VC10 1101 entered service with BOAC on 29 April 1964, operating between London and Lagos, Nigeria. It was followed by the stretched Super VC10 1152, which was 13 feet longer. The Super VC10 accommodated up to 187 passengers in a single-class, six-abreast configuration and served as a true transatlantic rival to the 707 and DC-8. This fixed the Comet’s range problem.

The Super VC10 was quiet and solid. Passengers liked it, and load factors were high. However, its rear-engine, T-tail design made the structure heavier and operations costlier, even though it had almost a 5,000-mile range. This led BOAC to replace the VC10 with the 707, despite objections from the British government.

After airports on Commonwealth routes were equipped with longer runways, the VC10 was no longer needed for them. Production stopped after only 54 Standard and Super VC10s were made, despite the aircraft being a superbly engineered jetliner.

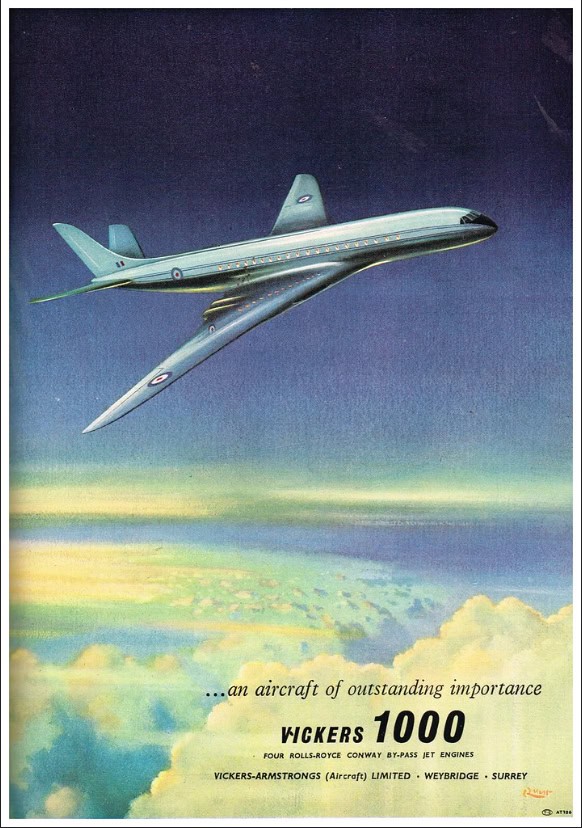

The Boeing 707-320 and Douglas DC-8-30 became the world’s first intercontinental jetliners. However, tucked away in the final assembly hall in Wisley, England, was an airframe taking shape that could have claimed this title two years before the US designs did. This was the Vickers V1000. Unfortunately, it never saw the light of day and, thus, never had the opportunity to prove its worth.

The catalyst for the project was the Ministry of Supply’s (MoS) requirement for a speed-compatible troop transport to accompany the Royal Air Force’s (RAF) V-bombers on long-range missions. Vickers, which produced its own Valiant bomber, logically seemed the choice to meet it, and George Edwards became the program’s chief designer.

It was at the same time that the national carrier BOAC began to assess its own needs for a true transatlantic jetliner, as its Comet 1s offered limited passenger capacity and lacked the range to operate such routes.

Designed as a larger, longer-range, and more advanced successor, the V1000 measured 146 feet in length and featured a fuselage built with thicker-gauge metal skin. The pressurized aircraft incorporated a multi-pane windscreen, forward and aft passenger doors on the port side, servicing doors on the starboard side, 18 elliptical cabin windows, four overwing emergency exits, and two underfloor baggage and cargo holds.

A 140-foot, compound-swept wing with a 6.0:1 aspect ratio and 3,263 square feet of area had 38-degree inner and 28-degree outer sweeps, solid milled spars, and advanced flaps. Lateral control used two-section ailerons.

The conventional tail consisted of a swept vertical, fuselage-integral fin with a three-piece rudder and horizontal stabilizers mounted at considerable dihedral to avoid jet exhaust interference.

Power was provided by four wing root-installed, 15,000-thrust-pound Rolls-Royce Conway aft-fan engines, the world’s first low-bypass-ratio turbofans.

Representing Britain’s opportunity to lead the world commercial aviation market with a large-capacity, long-range intercontinental variant of the V1000, designated VC7—and adding to its achievements of having designed the world’s first successful turboprop Viscount and pure-jet Comet —the type, with a 90 percent completed prototype that was only six months from its first flight, was canceled.

The VC7’s transatlantic range, which would have enabled it to both precede and then compete with the quad-jets then under development on the US West Coast, was compromised by structural weight increases, necessitating 17,500 thrust-pound versions of the Conway engine, which Rolls-Royce was amenable to designing. Cost escalations and program delays inevitably made negative inroads into what was Britain’s hope for commercial jet aviation superiority.

Despite the V1000’s and VC7’s design advancements and the anticipated success they could have achieved as both a single aircraft and a representation of the British aircraft industry, being first was only one element in the formula. Being superior was another aspect, and one retrospective view highlights two potential shortcomings that could have impacted sales—namely, a cruise speed that was approximately 40 mph lower than that of the US quad-jets and a higher gross weight.

Soviet Solutions for Intercontinental Jet Travel

Although Russia’s first jet airliner, the Tupolev Tu-104, was an adaptation of the Tu-16 Badger, sharing the same wings, Mikulin turbojets, tail, and undercarriage, this 50-passenger airliner, with a 1,500-mile range, could hardly be considered a long-range one. However, it can be credited with being the first to operate sustained jet service, as the Comet was grounded for four years while the cause of its explosive decompressions was investigated, and the type re-emerged as the stretched Comet 4.

Like Britain, the Soviet Union ultimately fielded a true competitor in the race to develop early long-range jet airliners with the introduction of the Ilyushin Il-62, which featured clean, swept wings, an aft fuselage-mounted 23,150-pound-thrust Kuznetsov NK-8-4 turbofan, and a T-tail, bearing a striking resemblance to the Super VC10.

Accommodating almost 200 in its final version and powered by 23,350 thrust-pound Soloviev D-30KU engines, it featured a 6,400-mile range and enabled Aeroflot to operate intercontinental services to Montreal, New York, and Tokyo with it.

China’s Attempt at an Indigenous Long-Range Jetliner

Little-known, the Shanghai Y-10 could have represented the Chinese aircraft manufacturers’ successful attempt to produce a quad-engine, long-range, narrow-body jetliner in the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8 class, thus filling national carrier CAAC’s needs for such an indigenous counterpart. But its inferior, reverse-engineered, pieced-together nature, lack of safety, and three-decade-old technology foundation left it little more than an aerial test vehicle that never entered service.

Catalyst to the Shanghai Y-10—Yun-10 or “Transporter-10” in Chinese—was Wang Hongwen, who had significant influence in the Chinese Communist Party and was the youngest member of the Gang of Four. He proposed an aircraft that would fulfill the dual purpose of initiating the country’s indigenous aviation design and manufacturing industry, while maintaining Maoist isolationism.

The overall configuration, based on technical drawings completed in June 1975, was highly suggestive of the Boeing 707, but with a modified cockpit window layout and a shorter fuselage, resulting in an overall length of 140.10 feet.

As had occurred with other western design copies, such as that of the Ilyushin Il-62, which strongly resembled the Vickers VC10 with its four aft-mounted turbofans and t-tail, and the Tupolev Tu-144, which, in essence, was an attempt to offer an Aerospatiale-British Aerospace Concorde equivalent, it appeared to be based upon an existing aircraft.

A lack of aluminum alloy skins and their thicker gauge resulted in higher empty and gross weights, respectively, of 128,133 and 224,872 pounds, which increased fuel consumption and seat-mile costs.

The wings, whose span ultimately became 138.7 feet, gave the delusion that engineers had succeeded in copying those of the 707, but reverse-engineering attempts had failed, and the same process was employed by using those of the Hawker Siddeley Trident.

Power was originally to have been provided by Chinese-designed, Pratt and Whitney JT3D-copied WS-8 engines, but oil leaks forced the use of reverse-engineered engines from a 707 that crashed in Urumqi on 19 December 1971.

Internally, the Shanghai Y-10 could accommodate 124 mixed first- and economy-class passengers, 149 in an all-coach arrangement, or up to 178 in a single-class, high-density one. The five-person cockpit crew consisted of the pilot, copilot, flight engineer, navigator, and radio operator.

Its maximum payload gave it a range of 3,450 miles. Its maximum and cruise speeds were, respectively, 605 and 570 mph, and its service ceiling was 40,450 feet.

Production of the Y-10 commenced in June of 1975 and three airframes were ultimately built—a static test example (01), which was subjected to 1,400 hours of wind-tunnel testing; a flying prototype (02), B-0002, which first flew on 26 September 1980 under the command of Captain Wang Jinda; and a fatigue-test airframe (03), which, like the static-test one, never actually took to the sky.

Aircraft B-0002 nevertheless undertook handling characteristic assessment flights, including one that kept it airborne for four hours and 49 minutes, one that covered 2,236 miles, and one that surmounted Mount Everest. A familiarization tour took it to Beijing, Chengdu, Guangzhou, Harbin, Hefei, Kunming, Lhasa, and Urumqi.

Although CAAC, which could not only have acquired the type, but could have done so on behalf of other Chinese state carriers, failed to place a launch order with the face-saving explanation that its needs had already been met with other types, it found its technology inferior to the point of being viewed as unsafe, leading to program cancellation in 1985 after the single flying prototype had amassed 170 airborne hours during 130 fights.