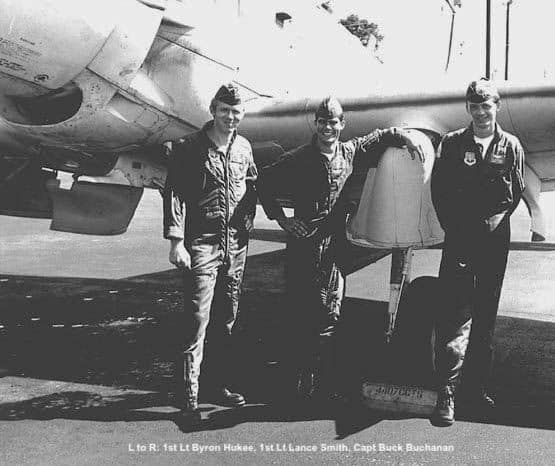

“My Fighter Career” is a limited series of articles by Byron Hukee. He’s a humble, bad ass, retired USAF pilot who flew everything from the F-100 to the F-16. You can read his previous posts here:

Part 1: “I Wasn’t Born to Fly”

Part 2: The F-100 Super Sabre Is My New Ride

Ready for My New Jet…I Mean Prop

In early July 1971, following my basic survival training course at Fairchild Air Force Base (AFB) and water survival training at Homestead AFB, I headed to Hurlburt Field, Florida for Douglas A-1 Skyraider training. I had also been given a port call date of 13 October for my remote overseas assignment to Nahkon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base (RTAFB) with the 1st Special Operations Squadron (SOS).

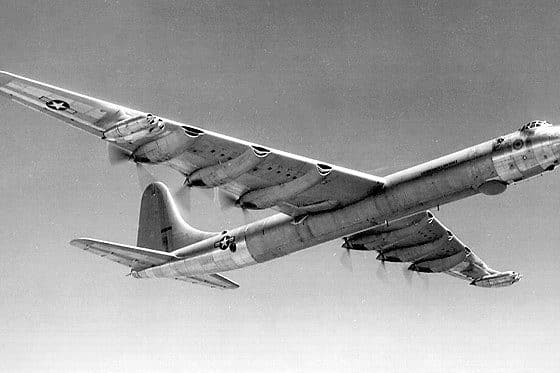

The Skyraider had already been in service with the USAF since 1964 in Southeast Asia. Since that time, it was also operated by the US Navy from their carriers in the Tonkin Gulf and by the Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF). The Vietnamese had seven fighter squadrons at five air bases in South Vietnam. In fact VNAF pilots were also being trained in the Skyraider at Hurlburt Field while I was there.

The Skyraider was a magnificent beast and was powered by the Wright Cyclone R-3350 18-cylinder radial engine. This made the Skyraider the largest single engine operational attack aircraft ever built. (the Martin AM Mauler was larger with its R-4360, but only 131 were built and it served only between 1948-1953).

Our flying training program consisted of 45 sorties and 60 hours of flying time. My logbook shows 41 sorties and 68 hours. 95 hours of academic training were mixed in with flying training. We were kept busy every day of our three-month training program.

Switching Aircraft Isn’t Easy

Converting from one aircraft to another is difficult enough, but converting from a single-engine jet fighter to a single-engine recip attack tail-dragger is quite another thing. New words and terms that were previously unfamiliar to me were like learning a foreign language. Here is a sampling of new terms we were faced with:

‘Torque Meter’, ‘Cylinder Head Temperature’, ‘Prop Pitch Control’, ‘Mixture Control’, ‘Oil Cooler Door’, ‘Cowl Flaps’, ‘Fuel Boost Pump’, ‘Carburetor Air’, ‘Supercharger Control’, ‘Tailwheel Lock’, ‘Dive Brake’, ‘Windshield Degreaser’, ‘Manifold Pressure’, ‘Windshield Wiper’… Wow!

Admittedly, most of these terms relate to the engine and not the airframe. It did boggle my mind though for quite a bit. Before we were scheduled for our first flight in the A-1, we had to get cockpit time on aircraft sitting on the ramp to become familiar with the location of all the controls in the cockpit. We then had to pass a “blindfold cockpit” test in order to be cleared to fly. We literally had to put on a blindfold and then touch the control lever or handle that the instructor called out. Eventually I completed this to the satisfaction of the instructors and we went out for my first orientation ride in the right seat of the A-1E.

I Learned From the Best

As in the F-100 program, the A-1 instructors were all combat veterans of at least one combat tour. My Instructor Pilot (IP) had served a tour at Pleiku in the 6th Air Commando Squadron . He went by the nickname of “Stretch” for obvious reasons. Stench was 6’ 5’ and weighed maybe 185 pounds. Stretch was my idea of a perfect IP, demanding, but not too demanding. He was patient and worked with me to get through what for me was the toughest part of the checkout. the first part was the hardest, consisting mostly of basic aircraft handling and takeoffs and landings. The first thing my IP said when I started to climb in the right cockpit for my “dollar ride” in the was be extremely careful climbing up on to the wing because it is slick as snot because oil from the engine works its way down the engine cowl and coats the right wing root with lots of it. He was right, I nearly busted my ass getting out of the cockpit and down the wing after the mission!

Flying this Beast was Difficult!

Flying this aircraft with the big 13’ 6” diameter 4-bladed prop powered by a 2,700 horsepower reciprocating radial engine meant that there was lots of torque. That torque continually made the aircraft yaw right on the ground during takeoff, and roll and yaw right in flight with high power settings. This of course had to be countered with left stick and left rudder. It took quite a bit of time before I got the hang of it when doing relatively simple maneuvers such as a chandelle or barrel roll. Unlike a jet powered aircraft, different amounts of control input were required depending on the direction of the turn or roll. The chandelle was the most difficult. It seemed to me that despite my best efforts, in the beginning, I seemed always to guess wrong. Eventually I got the hang of it.

Once I Learned How to Fly the Thing, Then the Fun Began

Once basic aircraft operation became less of a concern, we moved on to air-to ground weapons delivery both in a controlled box-pattern environment and later in a tactical less structured environment on the tactical range. Bombing on the scrabble range was a piece of cake compared to what I had just experienced in the F-100. In the A-1, we were going about half as fast in the F-100. We were dropping ordnance from much lower altitudes so I found this relatively easy and scored well.

For example, in the F-100 we had a 2,000 foot foul line for low angle strafe with a minimum (foul) altitude of 1,000. In the A-1, the foul line was 1,200 feet and the minimum (foul) altitude was 100 feet! Since the rate of fire for the 20 mm cannons in the A-1 was about 12 rounds per second (as opposed to 100 rounds per second for the M-61 gatling) it was possible to fire a 2 round sighter burst with both loaded guns armed, one round out of each barrel! The tricky part with ordnance delivery was having the ball centered (yaw) at release or you would probably have left or right error. We would typically “trim” the ball out to the left in the pattern so that as we accelerated to release airspeed, the ball would likely be centered.

Dive bombing was also greatly simplified as compared to the faster F-100. Our pattern airspeed was 150 Knots Indicated Airspeed (KIAS) at an altitude of 5,000 Above Ground Level (AGL). Release altitude for a Mk-82 (500 pound General Purpose [GP] bomb) was 2,300 feet AGL at 270 KIAS in a 40° dive angle. This allowed ample safe separation to escape the frag pattern of the ordnance with a 4 second fuse setting.

Quarterback of the Skies

During our ground attack training, we were also trained on how to control airstrikes from other aircraft. We were directing airstrikes as we later would do in combat as a Sandy during a SAR mission. This training became very important as I would soon find out once I left the states and my family behind for my one year combat tour in the A-1 Skyraider. At our class get-together following completion of our training, Stretch pulled me aside and gave me two pieces of advice. He said, “Don’t ever duel with Anti Aircraft Artillery (AAA) guns, and there is nothing over there worth dying for.” I understood loud and clear the first advice, but was somewhat puzzled about the second. Weren’t we fighting to protect the interests of the US? Much later, I realized he was indirectly commenting on the political nature of the Vietnam War.

After completion of this training, my family and I went back to Minnesota. My wife and young son lived there during my one-year combat tour.