In the early 1950s, a team of designers thought it would be a good idea to not only design but actually build the wacky contraption called the de Lackner HZ-1 Aerocycle. Why would they build it?

Developed in response to an idea for the development of one-man flying platforms, the HZ-1 was envisioned as a highly mobile military recon and transport vehicle for use on the then-much-anticipated ‘atomic battlefield’.

A Dangerous Looking Idea

The HZ-1’s design incorporated a unique control system. Or maybe more accurately put, a control method, based on a then-novel concept known as ‘kinesthetic control’. ‘Twas thought up by Charles H. Zimmerman, an aeronautical engineer with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA).

If Zimmerman’s name sounds familiar to you, then you’re probably a Vought fan. Or maybe you just like really weird things with wings. He designed the Vought XF5U ‘Flying Flapjack’ and its predecessor, the V-173 ‘Flying Pancake’ for the U.S. Navy during the early 1940s.

Great, now I’m hungry and gotta head to IHOP…

Zimmerman’s concept of ‘kinesthetic control’, well… if you want an in-depth explanation, you should google it because I ain’t smart enough to write about stuff like that. In a nutshell, though, it’s all about using the natural physical inclinations of the human body as a flight control system.

This is where the word ‘crackpot’ came to mind for some folks back then.

Screwy Idea, But Simple… Right?

The HZ-1 Aerocycle was propelled by 15-foot twin contra-rotating rotors driven by a 40-ish horsepower Mercury Marine outboard engine. It had a twist-throttle on handlebars, similar to that which you would find on a motorcycle.

The landing gear consisted of five rubber airbags. That is four small bags attached to the ends of booms arranged in an ‘X’ configuration and extending out horizontally from the main structure of the vehicle, with a fifth, larger bag directly underneath the main structure.

It Could Even Land On Water…Probably Once

The bags doubled as flotation devices, allowing the HZ-1 to land on water, though likely only in calm sea states. The bags were later replaced with a skid setup as used on many helicopters.

Mere Inches Above A Spinning Blade

The pilot stood on a tiny platform mounted right next to the engine and directly above the rotors. his body loosely secured to the main structure of the vehicle by a safety tether and his feet held in place by straps.

Here’s where that kinesthetic stuff comes in: the vehicle’s primary means of maneuvering was the shifting of weight distribution. Consider the body’s natural senses that provide us with good balance and equilibrium. It was thought they would also provide an HZ-1 pilot the ability to maintain effective directional control of the vehicle.

So, if the operator leaned forward, the vehicle would dip slightly at the front, and the rotors would push the machine forward. Lean to the left, move to the left. To the right…

Pretty simple, yeah?

Having been designed with this whole kinesthetic thing in mind, the HZ-1 was intended for use by inexperienced infantrymen who had received a bare minimum of training in its operation… like… half an hour or so.

So, combat conditions.

Under fire.

Bullets whizzing past your head.

The human body’s natural response to said bullets’a-whizzin’ is often involuntary, jerky movements.

Meat-grinder rotor blades whirling below.

Yeah. What could possibly go wrong?

Rearing a Next Generation Foal

Humor aside, the notion that the HZ-1 represented a logical next step in continuing the evolution of the archaic horse cavalry is inescapable. First we replaced our equine friends with motorcycles, then moved on to light tanks and other armored fighting vehicles. Why not advance further, up into the air with something akin to a mechanical flying horse?

The original prototype, called the DH-4 Helivector, was designed by Lewis C. McCarty Jr. of de Lackner Helicopters Inc. in Mount Vernon, New York. The DH-4 flew for the first time in November of 1954. A second prototype, designated DH-5, first flew in January of 1955 at the Brooklyn Army Terminal (BAT), New York.

In addition to the pilot, the Aerocycle could carry 120 pounds of cargo, and could achieve a maximum speed of 75mph. It had a range of about 15 miles, and could stay airborne for roughly 45 minutes. The reported maximum ceiling was 5,000 feet, but… well… why anyone would wanna take this thing up that high is beyond me.

During initial testing at BAT, the Aerocycle seemed somewhat promising, and the Army ordered twelve examples for further evaluation, under the designation YHO-1 (soon to be re-designated HZ-1). Testing continued at BAT and other nearby locations before the program moved to Felker Army Airfield at Fort Eustis, Virginia in 1956.

Like Trying to Break a Bronco

Further testing brought certain flaws to light, most notably problems with the HZ-1’s operability. Chief test pilot at Fort Eustis was Captain Selmer Sundby, an experienced helicopter pilot who found the HZ-1 to be considerably more difficult to control than had been suggested.

Flights of the HZ-1 were rarely uneventful, filled with bumps and bounces, as well as both jerky and hesitant maneuvering. Control input was crucial, and versatility in technique was required. One had to be both subtle and aggressive, depending on the situation.

Sundby had doubts as to whether or not inexperienced infantrymen who’d never flown anything before could operate the Aerocycle safely at all, never mind after a mere half-hour’s worth of instruction. As it turns out, others had similar doubts. This included some within the media, as evidenced by this news clipping from 1956:

Aside from the hazards that such control difficulties could add to an already highly dangerous combat situation, there were also significant safety issues stemming from the vehicle’s very design.

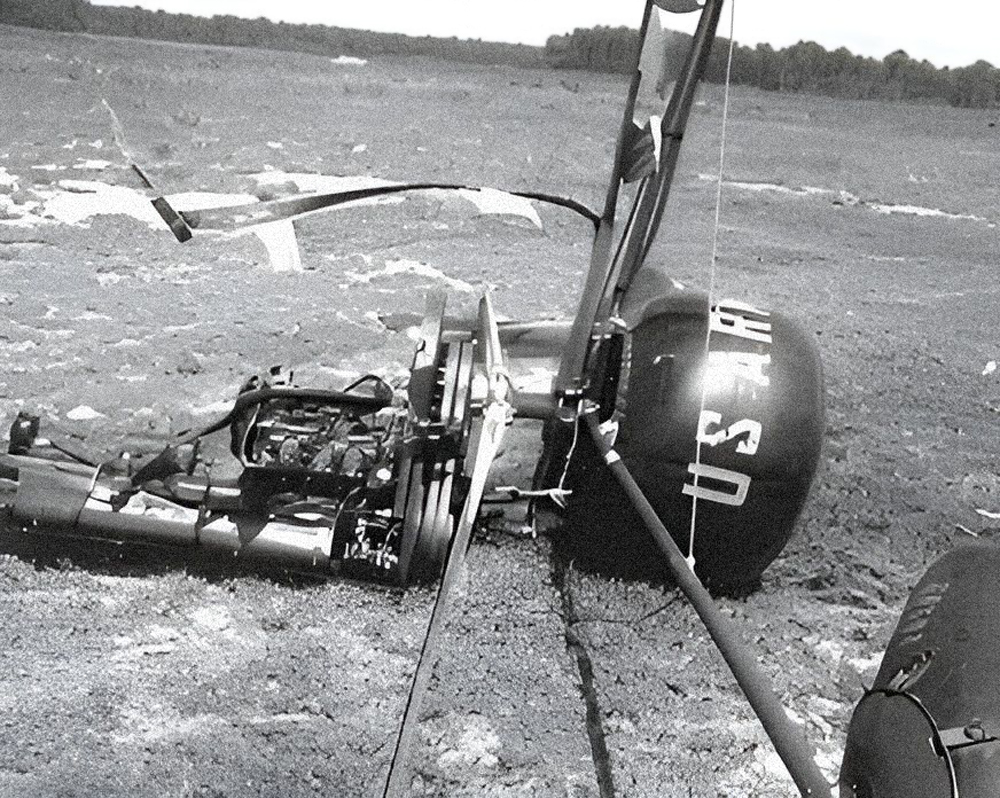

At least two accidents occurred during testing, caused by an inter-meshing of the type’s dual contra-rotating rotors. Your author is not certain which ‘oopsie’ is shown in the photo above, but in both instances the rotors flexed, struck one another, and shattered, resulting in the inevitable crash and a brief but highly undesirable transition of flight mode for the pilot. One incident occurred at an altitude of forty feet, and Capt. Sundby suffered a broken leg.

Throwing Riders

Here’s a news clipping that provides details of another incident in 1957. On this flight, the pilot was Professor Edward Seckel from the Department of Aeronautical Engineering at Princeton University, New Jersey.

After much investigation and testing in the full-scale wind tunnel at Langley Research Center, Virginia, other flaws, including stability issues, were identified. But the root cause of the rotor-strike problem could not be determined, and the program was ultimately abandoned.

Win, Place, or Show? No Bet.

Another reason for its demise was that the HZ-1 Aerocycle was proving far less useful than had been hoped. Helicopters had matured considerably since the early egg-beaters of the previous decade, and were now emerging as a much more efficient and effective means of providing aerial battlefield mobility.

Cue footage showing droves of Bell UH-1 Hueys dropping green-camo-clad, M16-toting grunts into a hot LZ in the middle of the lush greenery of a Southeast Asian landscape, accompanied by the soundtrack of rotor blades thumping, cracking small arms fire, barely intelligible radio comms burning through static, and the Stones’ ‘Paint it Black’ playing in the background.

The days of the one-man flying platform were over, having run their course in less than a decade. The HZ-1 Aerocycle simply turned out to be an impractical idea that progressed as far as it did largely because of its novelty and man’s necessary curiosity.

Many a road to success is paved over a footpath of failure. And in the end, the Aerocycle was swept aside to make way for greater things.

The HZ-1 Aerocycle Still Has Its Place In History

in all, fourteen Aerocycles were built, and just two survive today: one in the collection of the U.S. Army Transportation Museum at Fort Eustis and another at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.

Think of these two survivors as reminders that, though genius is often coupled with more than a bit of madness, in the end, this particular crazy idea turned out to be just that – freakin’ nuts.