Dense fog had settled over Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport (DTW) on the afternoon of 3 December 1990.

The visibility was dropping by the minute, and the airport surface had become a maze of blurred centerlines, indistinct taxiway edges, and half-invisible signage. Inside that haze, two Northwest Airlines jets found themselves on the same runway without ever seeing each other until it was far too late.

What happened that December afternoon at DTW remains one of the most studied runway incursions in modern aviation.

Two Flights Departing Detroit, Two Very Different Situations

Northwest Flight 1482 was a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-14 (reg. N3313L) operating from DTW to Greater Pittsburgh Airport (PIT), which is now Pittsburgh International Airport. The aircraft pushed back from Gate C18 at approximately 1335 local time and was cleared to taxi to Runway 03C via Taxiway Oscar 6, Taxiway Foxtrot, and Taxiway X-Ray.

The assignment was clear. The environment around them was not.

Oscar 6 sat in an area of the field where markings were already faded, even in good weather. Additionally, visibility had dropped to roughly one-quarter of a mile (something not reflected in ATIS information until minutes before the collision). The temperature was 41 degrees (F) and rising.

The crew struggled to identify their correct turn. They taxied past Oscar 6 without realizing it and entered the outer taxiway instead. Ground control saw the mistake on the airport diagram and redirected them toward Oscar 4, with instructions to join X-Ray.

Inside the cockpit, the crew worked to interpret the signs they could barely see. They believed they had found X-Ray. In reality, they had not. Their next turn placed them directly onto Runway 03C, very near the intersection with Runway 09/27. They had entered active pavement at one of the busiest and most complex points on the field in conditions that erased nearly all visual cues.

When the captain realized they were no longer on a taxiway, he stopped the airplane near the left edge of Runway 03C and called ground control. He reported that the aircraft was “stuck.” The fog outside the windows was so thick that neither pilot could orient themselves with confidence. The controller instructed them to leave the runway immediately. There was no time to do so.

Only a few seconds remained.

Meanwhile, a Boeing 727 Begins Its Takeoff Roll

Northwest Flight 299, a Boeing 727-251 (reg. N278US), was preparing for departure from DTW to Memphis International Airport (MEM). The aircraft had been cleared to Runway 03C as well. The crew had also noticed that the visibility seemed worse than the 0.75 miles reported via ATIS. They even remarked on it. The numbers did not match what they were seeing through the windshield, but the ATIS had not been updated. Their takeoff clearance remained valid.

Captain Robert Ouellette positioned the aircraft on the runway and completed the final items on the before takeoff checklist. Once everything was in order, he advanced the throttles, and the Boeing 727 began accelerating through the fog. They were passing through more than 100 knots, committed to the takeoff, when a silhouette materialized through the murk ahead of them.

It was the DC-9.

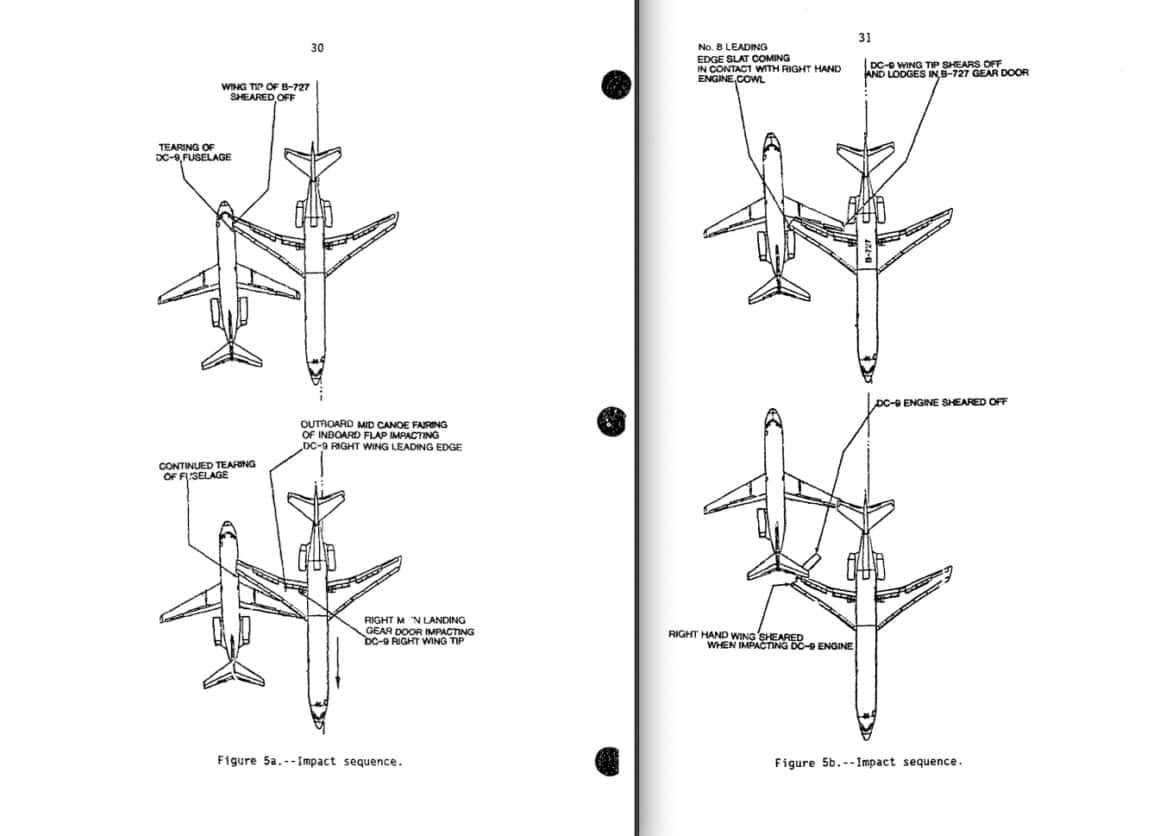

Ouellette attempted to swerve left when the aircraft appeared, but there was simply no room and no time. The right wing of the Boeing 727 struck the right side of the DC-9’s fuselage just below the passenger windows. In the same motion, the impact sheared away the DC-9’s number two engine. The smaller aircraft ignited almost immediately as fuel and debris sprayed across the scene.

Inside the Boeing 727, the crew safely brought the aircraft to a complete stop on the remaining runway using maximum braking. Once stopped, the captain shut down all three engines, confirmed there was no immediate danger of fire, and directed the passengers to deplane through the rear airstair.

All 154 people aboard Flight 299 survived without injury.

Inside the DC-9: Fire, Smoke, and an Evacuation with Critical Failures

The collision destroyed much of the right side of Northwest Airlines Flight 1482. Fire spread rapidly through the cabin. The usable escape routes were limited. The pilots exited through the left sliding cockpit window. The remaining survivors fought through heat and smoke to reach the left overwing exit or the left main boarding door. Eighteen passengers escaped through the left overwing exit. Thirteen escaped through the left main door. Four others jumped from the right service door before flames overtook that area.

One of the most tragic failures occurred at the tail. The DC-9 tailcone contains a built-in evacuation exit that can be released from inside the aircraft. The release mechanism had been improperly rigged. When passengers and a flight attendant attempted to use it, they were unable to release the exit. Both the flight attendant and one passenger succumbed to the smoke and toxic fumes in their attempt to open the tailcone exit.

In total, eight people aboard the DC-9 were killed, and ten were seriously injured. Thirty-six survived.

The Human Factors Behind the Taxi Error

The NTSB found that the cockpit dynamic on Flight 1482 played a major role in setting up the sequence of errors. The captain had just returned from a six-year medical leave and was still adjusting to new manuals, procedures, and a different airline culture resulting from the mergers that had occurred during his absence. He had not yet attended Crew Resource Management (CRM) training because Northwest Airlines did not have a program in place at the time, unlike other carriers.

READ MORE ABOUT NORTHWEST AIRLINES ON AVGEEKERY

- Northwest Airlines’ 84-Year Legacy of Bold Innovations as an Aviation Pioneer

- Whoops! A Northwest DC-10 Once Landed in the Wrong Country

- D.B. Cooper: The Boeing 727 Legend Born on a Stormy Thanksgiving Eve

The first officer, hired only seven months earlier, projected a strong sense of confidence. He made several claims about his background that were later found to be exaggerated. He implied that he was highly familiar with DTW operations when, in fact, he was not. The captain accepted those claims at face value. The result was an unintended shift in cockpit authority. The NTSB described it as a near-complete reversal of roles. Instead of leading, the captain relied heavily on the first officer and deferred judgment in situations where he should have asserted command.

That imbalance left the crew uncoordinated during one of the most unforgiving taxi environments in the country that day. Confusing airfield signage and diminishing visibility only magnified the consequences.

Air Traffic Control and Airport Infrastructure Shortfalls

The NTSB also identified several institutional and environmental factors that contributed to the conditions that led to the accident.

Surface markings and signage at DTW were woefully inadequate. Many markings were faded and difficult to see, even in clear weather. The signage at the intersections near Oscar 4 and Foxtrot created opportunities for misinterpretation. Lighting systems were also insufficient for the prevailing conditions.

Visibility reporting in the tower was inaccurate. An off-duty controller correctly noted that visibility was closer to one-eighth of a mile, but the on-duty controller did not update the official report. This had direct influence on the Boeing 727 crew, who relied on the published visibility to justify continuing the takeoff (visibility mins for a Runway 03C departure was a quarter mile).

Ground control did not provide progressive taxi instructions even after it became clear that the DC-9 crew was uncertain of their position. By the time the tower realized that Flight 1482 was actually stopped on Runway 03C, the Boeing 727 had already been cleared for takeoff for nearly a full minute. The tower controller believed that Flight 299 had already lifted off. The assumption proved to be incorrect and proved critical.

The FAA had not corrected deficiencies on the airport surface, despite the fact that DTW’s taxiway network was notoriously complex and had a history of confusing signage.

The Collision Sequence in Detail

The final moments unfolded quickly. The DC-9 crew, still uncertain about their exact position, edged slightly forward while discussing their surroundings. The first officer mistakenly reported that they were holding short of Runway 09/27. The captain doubted this, but the fog was so heavy that they were effectively navigating blind.

“It looks like it’s going zero zero out here,” FO James Schifferns said at one point. Later, he added, “Man, I can’t see shit out here.”

It looks like it’s going zero zero out here.

Northwest Flight 1482 FO James Schifferns

Flight 1482 was in a very precarious situation.

Ground control instructed them to exit the runway immediately. The DC-9 remained partially on the runway as the captain steered left in an attempt to find pavement that seemed safer. At that same moment, Flight 299 was accelerating toward them.

When the Boeing 727 appeared through the fog, the DC-9 crew had almost no time to react. The impact on the 727’s right wing tore open the DC-9’s fuselage, ripped off an engine, and left the aircraft engulfed in flames as it spun slightly from the force of the collision. The fire spread so quickly that first responders arriving moments later could do little but attack the flames from the exterior.

What the Industry Learned and Why It Matters

The accident prompted significant changes across multiple layers of aviation operations.

CRM became standardized. Northwest Airlines and many other carriers expanded CRM training to address authority gradients, communication breakdowns, and decision-making problems before they led to accidents.

Progressive taxi procedures became more widely used in low-visibility conditions. Controllers today are far more proactive in guiding aircraft step by step when crews report uncertainty.

Airport signage, lighting, and surface markings were improved not only at DTW but across the United States. Modern airports use clearer signage, more consistent lighting cues, and improved layout logic.

Runway incursion awareness training increased. The industry recognized that most surface accidents arise not from a single mistake but from a chain of minor misjudgments that accumulate into dangerous situations.

The importance of stopping the aircraft when uncertain became a central teaching point. Had Flight 1482 set the parking brake and waited for instructions the moment they realized they were lost, the collision might never have occurred.

A Foggy Afternoon That Still Teaches Today

The story of Northwest Airlines Flights 1482 and 299 is not only the story of a collision. It is the story of how quickly small deviations can snowball when weather is poor, communication falters, infrastructure lags behind, and cockpit roles become blurred.

Each link in the chain matters.

Unfortunately, for the lives lost at DTW on 3 December 1990, it would be a lesson learned far too late.