Jet Stream Winds Played Havoc with Bombs Dropped from 30,000 Feet Over Japan.

On 9 March 1945 the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) XX Bomber Command initiated Operation Meetinghouse. The Twentieth had been using their B-29 Superfortresses to bomb Japan from bases in the Marianas since November 24th 1944, and from bases in China since April of 1944. Results of their missions were unsatisfactory. A change was necessary. It was time for General Curtis LeMay.

The First Raids on the Homeland

America’s very first raid of the war on Tokyo took place on April 18th 1942, when USAAC Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle led sixteen twin-engine B-25B Mitchell bombers, launched from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8), to attack Japanese targets including Tokyo and Yokohama.

The bombers were to continue flying west after their attacks and land in China. Because the ships in the task force had stumbled upon Japanese picket boats, the bombers were forced to launch much earlier, and at much longer range from Japan, than planned.

A Morale Boost More Than a Victory

While the raid did little real damage, it provided a much-needed morale boost for an America reeling after Pearl Harbor and the subsequent Japanese sweep through much of the Pacific. The fate of the bombers was sealed when they took off so far from their planned departure point.

None of the bombers reached the planned recovery airfields in China. However, Japan was forced to commit resources to the defense of the home islands, which had been thought to be safe from American attack, for the remainder of the war.

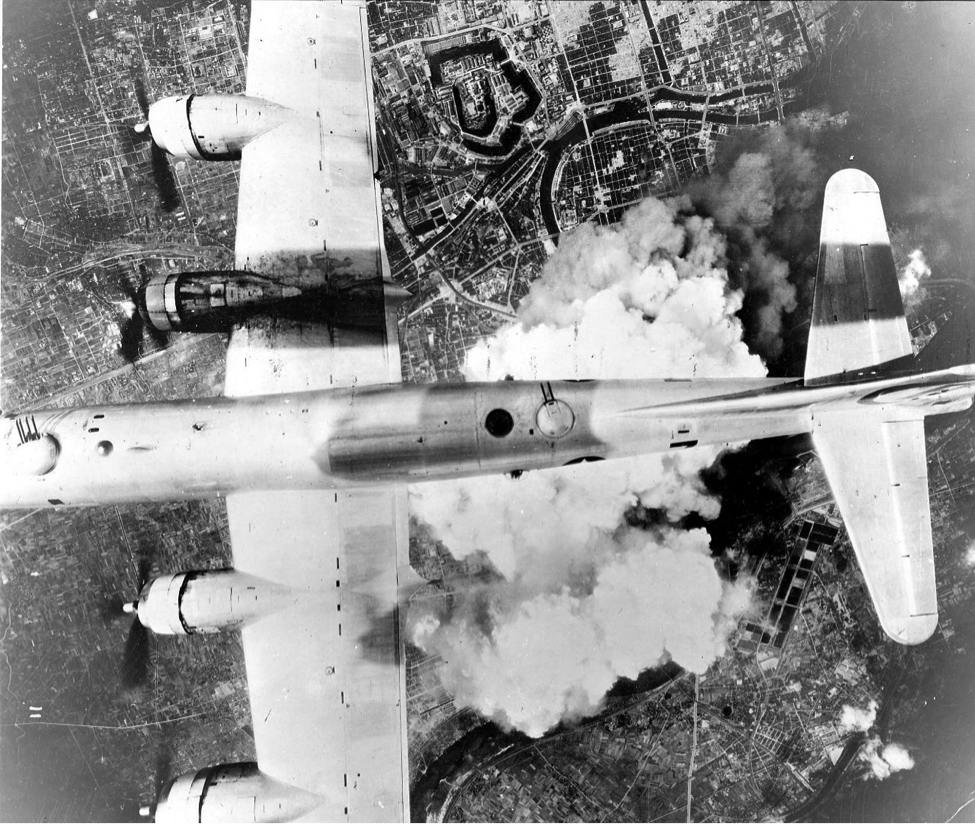

You Can’t Bomb From High Altitudes with High Winds

Fast-forward to 1945. Results of the high altitude precision daylight bombing of Japan by XX Bomber Command over the previous 11 months were unsatisfactory, due in large part to very strong high altitude winds aloft over Japan.

These winds, later to be recognized as the jet stream, made the approach to the target areas, the bomb runs, and egress from the target areas after bomb release over Japan problematic. In some cases, B-29 ground speeds were reduced to less than 100 miles per hour when bucking the strong headwinds. When bombing from high altitude, bombing accuracy was significantly reduced by the high winds affecting free-fall bomb trajectories.

The consistently cloudy weather over the Japanese islands also contributed to the overall lack of precision in high altitude precision daylight bombing.

LeMay Makes the Call

General Curtis LeMay, the new commander of XX Bomber Command, took one look at the results of the bombing of Japan from China since April, and especially from the new bases on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam since November, and decided to change the tactics employed by the Twentieth.

There would be no more high altitude precision daylight bombing of Japan. LeMay’s crews would bomb from low to mid-level, and they would bomb at night. The B-29 aircrews tasked with flying the missions harbored misgivings about the changes LeMay instituted.

Attacking between 5,000 feet and 9,000 feet seemed suicidal, and removing all the defensive guns from their bombers except the tail guns made little or no sense to the crews.