We remember Western Airlines, one of America’s iconic air carriers that offered innovative in-flight service.

It is Tuesday, 7 May 1957, and you are a passenger aboard Western Airlines Flight 70, a Douglas DC-6B that has just leveled off at its cruising altitude after an 0825 departure from San Francisco. The flight is bound for Salt Lake City and Denver. You are settled in with your newspaper and book.

Suddenly, you hear a bugle call and the sound of hoofbeats. The strange inflight noises emanate from a tape recorder attached to the serving cart, which is maneuvered down the aisle by two flight attendants dressed in English hunting attire. Eggs, steaks, sausage, ham, and Danish pastries are displayed on the cart. You are about to enjoy Western’s Hunt Breakfast, certainly the most elaborate morning meal service offered by a domestic US airline at the time.

While carriers back East also entertained their passengers with elaborate meal services during that era, the West’s own airline had developed a reputation for particularly fine inflight service.

Western Airlines was innovative when it came to serving its customers. The company’s Champagne Flights were famous throughout the industry, and gifts of small bottles of perfume or orchids for the ladies were touches of hospitality that the airline was known for.

IT HAD NOT ALWAYS BEEN STEAK AND EGGS

But things had not always been so rosy at Western. In 1949, the company eliminated meal service altogether while reducing fares by 5% in an experiment to see if such a move would attract more customers. At the time, the airline was desperate to cut costs and increase revenues after three unprofitable years in which net losses totaled $1.6 million, a staggering amount of money in the 1940s. The no-food experiment was a flop, and meal service resumed after six months.

By the end of 1949, Western was able to post a small profit. The company would continue to post profits every year during the next decade.

Terrell C. Drinkwater, the company’s president, instituted all of the above innovations and turned the airline around. He became famous among airline executives for Western’s dramatic transformation.

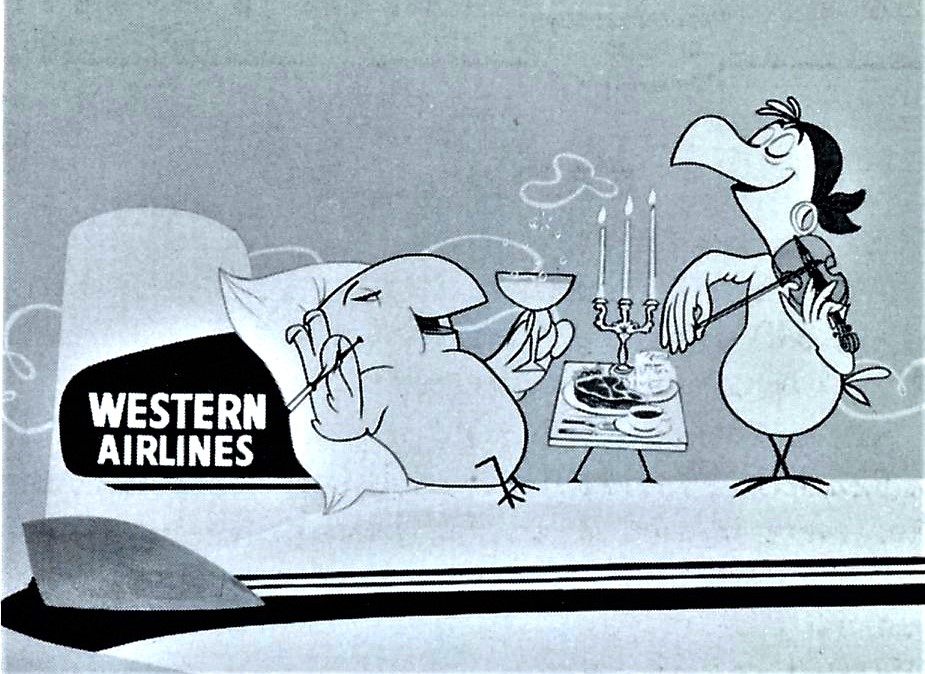

CHAMPAGNE FLIGHTS AND ONE IMPORTANT BIRD

Western’s first major innovation in inflight service took place in 1954, and it was a game-changer. The airline contracted with the owners of the Italian Swiss Colony brand to carry the winery’s champagne onboard its flights. The champagne was a complimentary offering, initially served as an accompaniment to meals aboard flights marketed as “The Californian.” The free champagne quickly became an enticement for passengers to book their travel on Western as opposed to the competition.

The flights that offered a snack or meal accompanied by the complimentary bubbly were eventually branded as “Champagne Flights,” and they became a hallmark of Western’s service.

In 1956, the airline celebrated its 30th birthday, and at about the same time, the company introduced an animated character to its television advertising campaign. The cartoon figure was a bird, somewhat resembling a parrot, resting atop a Western DC-6B with a cigarette holder in one hand and a glass of champagne in the other.

In the commercials, the bird would inform viewers that Western was “the ooonly way to fly!” The animated avian was christened “Relaxed Bird,” then VIB (Very Important Bird) by the company, but the public quickly dubbed the little character “Wally Bird.”

WESTERN AIRLINES FIESTA FLIGHTS

When Western inaugurated service to Mexico City in 1957, it did so with its usual champagne meal service. The following year, the company branded its non-stop First Class flights between Los Angeles and Mexico City “Fiesta Flights,” which featured lavish meals, a “Fiesta dessert cart,” and, of course, champagne.

The airline that at one time had eliminated all meal service in an effort to save money was now famous for some of the most innovative cabin service in the industry, from Fiesta Flights to Hunt Breakfasts.

In 1959, the company’s profit surpassed $5 million.

GOONEY BIRDS

Along with its fleet of DC-6Bs and Convair 240s serving cities throughout the West, the airline continued to be saddled with service to several small cities across the Great Plains that required Western to keep Douglas DC-3s in its fleet. By December 1958, the DC-3 operation had been reduced to one flight per day in each direction between Denver and the Twin Cities with eleven landings enroute, several of them on a flag stop basis. Most of these communities were eventually transferred to local service airlines, which were better prepared to offer service to such small cities.

Western could finally retire the last of its reliable old DC-3s, and the company’s system was now more streamlined and ready for the next step forward in commercial aviation.

INTO THE JET AGE

Before entering the 1960s, Western had selected the turboprop Lockheed L-188A Electra to supplement service operated with its reliable Douglas DC-6Bs, which would gradually be retired. But Drinkwater and his staff had not rushed into a deal to purchase the very first round of turbojets. Instead, Western took a deliberate, methodical approach, carefully evaluating the new generation of jets in development. That caution paid off: by waiting, Western was ultimately offered the ideal aircraft for its needs.

A slightly smaller version of the 707, the Boeing 720, was designed to offer a choice for airlines that wanted a jet for medium-length stages. Modifications of the original 707 design endowed the 720 with better field performance and a faster cruising speed. As airlines began ordering the 720, Boeing improved the design yet again by installing more powerful Pratt & Whitney JT3D fan engines, creating the Boeing 720B Fanjet. This is the aircraft that Western settled on, outfitted to carry 122 passengers in a mixed-class configuration.

While awaiting delivery of the 720Bs, Western leased two Boeing 707s from the manufacturer and introduced its first pure jet service on 1 June 1960 to Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle/Tacoma.

Boeing 720B service was finally inaugurated on 15 May 1961 between Los Angeles and Mexico City, followed shortly by service to the aforementioned Pacific Coast stations. Western’s satisfaction with Boeing’s Fanjet was demonstrated by the company’s acquisition of 27 720Bs between 1961 and 1968.

WESTERN’S BOEING 737

Western’s short and medium-haul routes were served well by the company’s turboprop Electras and aging piston-engined DC-6Bs. But more modern equipment, suitable for frequent take-offs and landings on flights making several stops, would have to be procured eventually. It was Boeing’s 737 that management decided would fit perfectly into Western’s fleet, even though the 737 design and production process was lagging behind the similar projects of Douglas and British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

In 1965, Western signed a contract with Boeing Aircraft to purchase 20 737s, plus options for an additional 10. The options were exercised, and the first of Western’s 30 factory-fresh 737s entered service in 1968.

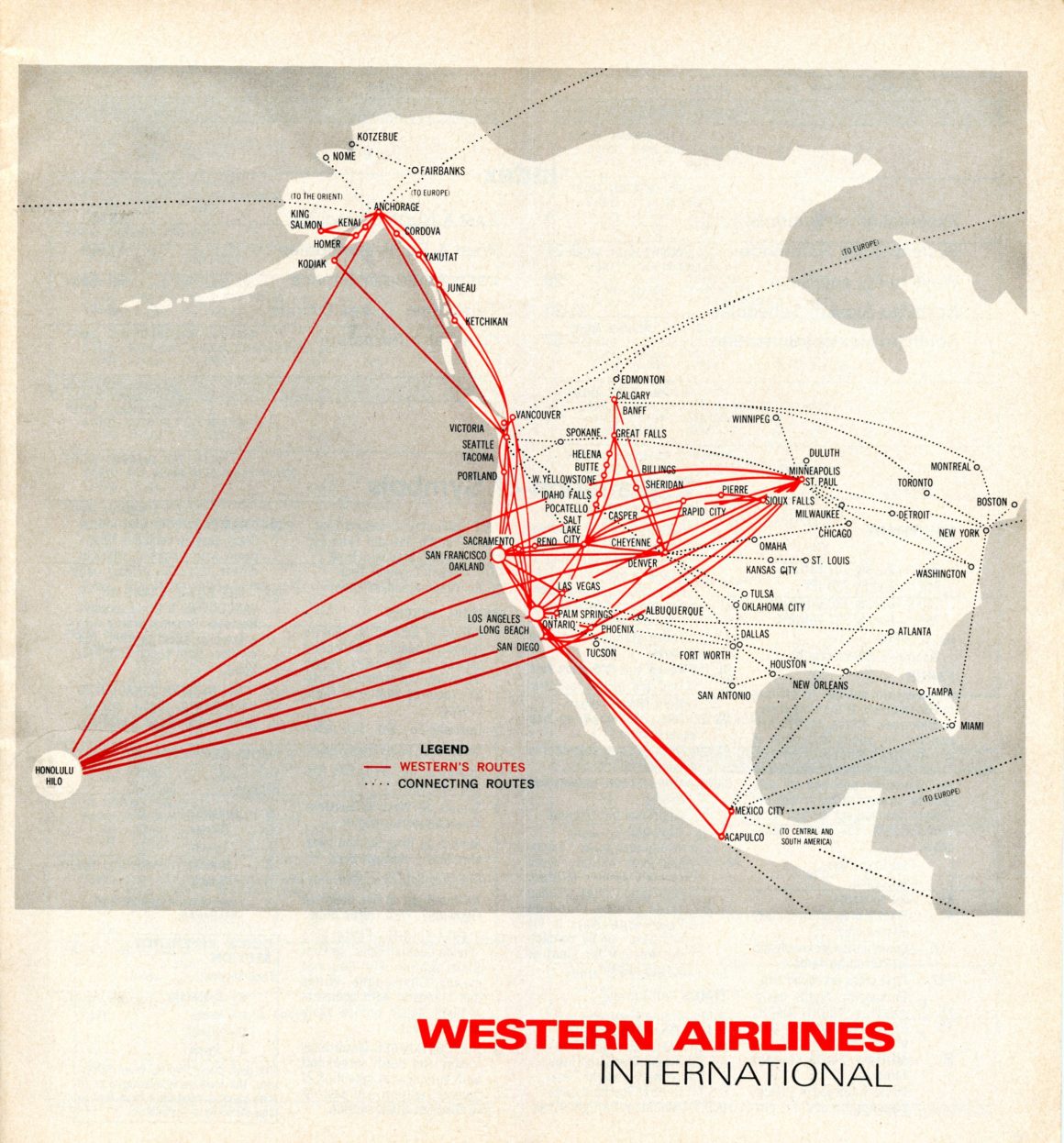

WESTERN AIRLINES TO ALASKA AND HAWAII

On 1 July 1967, Western absorbed Pacific Northern Airlines (PNA) through a merger, giving Western access to Ketchikan, Juneau, Anchorage, and other destinations in the 49th state.

In 1969, after perhaps the most convoluted and drawn-out case ever resolved by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), Western was granted permission to serve Hawaii from San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, several other mainland cities, and Anchorage.

In anticipation of the Hawaii award, Western purchased five Intercontinental models of the Boeing 707, which entered service in 1968. The 707-347Cs initially operated the company’s few long-haul services, from Los Angeles to Mexico City and from Los Angeles and San Francisco to the Twin Cities, before being deployed on the newly awarded Hawaii routes in the spring of 1969.

In addition to the intercontinental 707s and 30 new Boeing 737s, Drinkwater ordered six Boeing 727-200s and three Boeing 747 jumbo jets and was negotiating to buy more 727s and intercontinental 707s.

THE 1970s, ‘80s, AND THE END OF WESTERN AIRLINES

There was at least one observer who thought that the company was ‘in over its head’ and saw the potential for a takeover. Kirk Kerkorian was a developer, investor, and the former head of a supplemental air carrier, Trans International Airlines (TIA). He began acquiring shares of Western’s stock until he had accumulated enough to insist on placing his own people on Western’s Board of Directors.

The first thing Kerkorian wanted to do was cancel the 747 order. Drinkwater, who had guided Western since the 1940s, was forced out of the company in less than a year.

Western’s management settled on the McDonnell-Douglas DC-10 as its widebody aircraft of choice, and the company expanded operations to several destinations in the eastern US and, for a short time, to London’s Gatwick Airport (LGW).

During Western’s final years, the fleet consisted of Boeing 727-200s, Boeing 737s, and McDonnell Douglas DC-10s, while the company’s flight hubs were located at Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. In the post-deregulation era, the carrier became an attractive takeover target, and in 1987, Delta Air Lines acquired Western through a merger.

The air carrier that once proclaimed itself “the ooonly way to fly” was now relegated to history.