From his first solo flight, it was clear that Scott Crossfield had the makings of a true test pilot. According to his biographical material, Crossfield demonstrated his analytical flight test skills on that very first solo. His instructor was not available on the designated morning, so Crossfield, on his own, took off and went through maneuvers he had practiced, including spin entry and recovery.

During the first spin, Crossfield experienced vibrations, banging, and noise in the aircraft that he had never encountered with his instructor. He recovered, climbed to a higher altitude, and repeated the maneuver, with the same results. On his third spin entry, at an even higher altitude, he looked over his shoulder as the aircraft spun and saw the instructor’s door flapping. Reaching back, he pulled the door closed. The banging and noise stopped. Satisfied, he recovered, returned to the airport, and completed several landings. In later years, Crossfield often cited his curiosity about this anomaly—and his desire to analyze what was happening—as the true start of his test pilot career.

Crossfield was born in California on 2 October 1921. He served in the U.S. Navy as a flight instructor and fighter pilot during World War II. After earning his Master of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering in 1950, Crossfield joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards Air Force Base, California, as an aeronautical research pilot.

Breaking Barriers in Early Jet and Rocket Aircraft

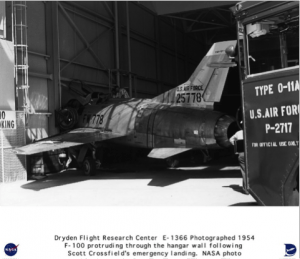

Crossfield was later assigned to flight test the North American F-100 Super Sabre, a supersonic jet fighter first flown in 1953. During a test flight in October 1954, its engine failed. The recommended procedure was ejection, as even North American’s own test pilots doubted a dead-stick landing was possible due to the aircraft’s high landing speed. Crossfield chose otherwise. He made a perfect approach and touchdown at Edwards, but the unpowered jet couldn’t stop in time. He narrowly missed several parked experimental aircraft before using the wall of the NACA hangar as a makeshift brake. Crossfield was uninjured, and the F-100 was repaired and returned to service.

Over the next five years, he flew nearly all the experimental aircraft being tested at Edwards, including the Bell X-1 (the plane Chuck Yeager had flown to first break the sound barrier), the Douglas D-558-I Skystreak, and the Douglas D-558-II Skyrocket.

On 20 November 1953, he became the first person to fly at twice the speed of sound when he piloted the Skyrocket to 1,291 mph (Mach 2.005). After 99 flights in the rocket-powered X-1 and D-558-II, Crossfield had more rocket plane experience than any other pilot in the world by 1955.

That year, Crossfield left NACA to become chief engineering test pilot for North American, where he played a major role in the design and development of the X-15.

The X-15 Program and its Lasting Legacy

The X-15 was an entirely new and unproven concept, and flight operations were considered extremely hazardous. It was Crossfield’s job to prove its airworthiness at speeds up to Mach 3 (2,290 mph).

The X-15 was a 50-foot-long rocket-powered aircraft with a 22-foot wingspan. It had a conventional fuselage but a wedge-shaped vertical tail, thin stubby wings, and side fairings that extended along the fuselage. It weighed about 14,000 pounds empty and approximately 34,000 pounds at launch. Its rocket engine, controlled by the pilot, could produce 60,000 pounds of thrust.

On 8 June 1959, Crossfield completed the X-15’s first flight, an unpowered glide from 37,550 feet. The controls had not been set up properly, and as he attempted to land, the X-15 went into what Crossfield described as a “pilot-induced oscillation.” He managed to set it down on the desert runway at the bottom of one oscillation, saving both himself and the aircraft.

Crossfield introduced several design innovations, including relocating rocket engine controls to the cockpit. Previously, technicians made all adjustments from the ground based on flight test data.

The X-15 was eventually powered by a single XLR-99 rocket motor, but early in the program it used two smaller XLR-11 engines. On his third flight, one of these engines exploded shortly after launch. Unable to jettison propellants, Crossfield was forced into an emergency landing, during which the stress on the aircraft broke its back just behind the cockpit. He was uninjured, and the aircraft was later repaired.

He had another close call during ground testing of the XLR-99. While seated in the cockpit of X-15 No. 3, a malfunctioning valve caused a catastrophic explosion. Though unharmed, Crossfield had been subjected to nearly 50 Gs in an instant. Years later, he admitted he began having trouble with night vision after the accident.

Other pilots in the program would eventually fly the X-15 into space, earning astronaut wings. Though Crossfield had hoped to be among them, the Air Force ordered him to “stay in the sky, stay out of space.”

Crossfield flew 16 captive flights attached to the modified B-52 Stratofortress and 14 of the 199 total X-15 missions. He piloted the first successful glide flight, the first powered flight, the first flight with the XLR-99 engine, and the first emergency landing. In 1962, he and two other X-15 pilots received the Collier Trophy, presented by President John F. Kennedy.

When asked to name his favorite airplane, Crossfield would reply, “the one I was flying at the time,” because he thoroughly enjoyed them all and their unique personalities.