Despite months of political pressure, dramatic headlines, and legislative maneuvering, it appears that Space Shuttle Discovery is not leaving the Smithsonian. For now.

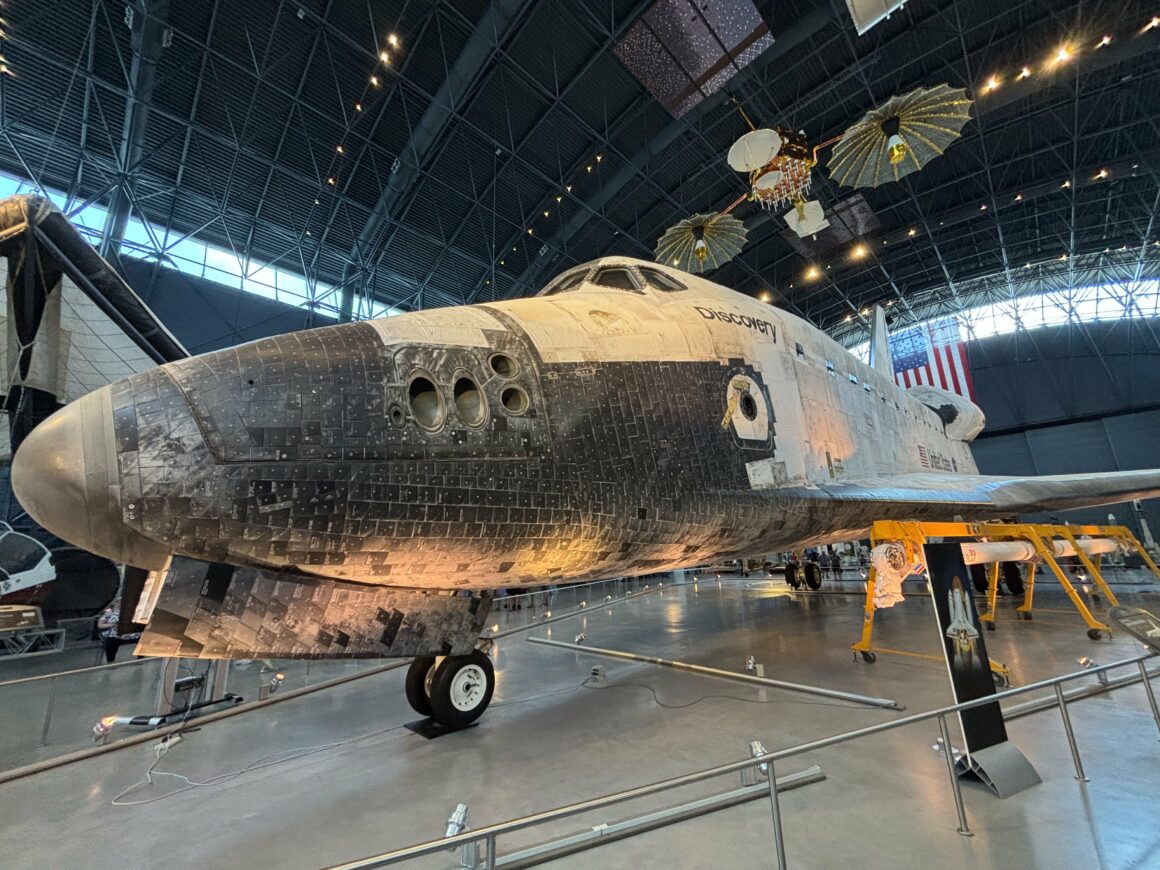

As of early 2026, the most flown orbiter in NASA’s Space Shuttle fleet remains on permanent public display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, where it has been since April 2012. There is no approved plan, funded pathway, or safe method currently in place to relocate the historic spacecraft to Houston. According to NASA leadership, the risks and costs involved may be too high to justify the move at all.

For now, Discovery stays exactly where she belongs. Preserved intact and accessible to the public.

A National Treasure Preserved Intact

Space Shuttle Discovery is an American symbol of progress and ambition. It is the most flown orbiter in NASA’s Space Shuttle program.

Over 27 years of service, Discovery completed 39 missions, spent 365 days in space, traveled nearly 150 million miles, and carried 251 crew members across 184 individual spaceflights. No other orbiter flew more missions or supported a broader range of objectives.

Discovery launched and serviced the Hubble Space Telescope, helped assemble the International Space Station, deployed interplanetary probes, and twice served as NASA’s Return to Flight orbiter following the Challenger and Columbia disasters. In 1998, it also carried John Glenn back into orbit, making him the oldest human to fly in space at the time.

NASA retired Discovery after the STS-133 mission in March 2011. In April 2012, the agency transferred the orbiter to the Smithsonian Institution, conveying full ownership. Discovery was delivered intact aboard a modified Boeing 747 and placed on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center, where it has remained ever since, preserved as closely as possible to its final flown configuration.

The Push to Move Discovery and the Reality of the Cost

In 2025, Texas Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz renewed efforts to relocate Space Shuttle Discovery to Houston, arguing that Mission Control and astronaut training were historically centered at NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

That effort culminated in a provision included in President Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” signed into law in July 2025. The provision authorized $85 million to transfer a space vehicle that had flown astronauts to a NASA center involved in the Commercial Crew Program. While Discovery was not named explicitly in the bill, Texas lawmakers made clear it was the intended vehicle.

The proposal quickly ran into major obstacles.

NASA and the Smithsonian jointly estimated that relocating Discovery would cost between $120 million and $150 million, excluding the cost of building a new facility to house the orbiter. Other estimates placed total costs, including construction, as high as $325 million.

More critically, both organizations warned that Discovery cannot be transported intact. The two Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCAs) used to ferry orbiters were retired years ago and are now museum artifacts themselves. Any overland or maritime move would require partial disassembly of the orbiter, a process that would permanently alter and damage the historic spacecraft.

NASA’s Administrator Hits the Brakes

After taking office in December 2025, NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman publicly questioned whether the relocation of Space Shuttle Discovery could or should proceed.

In a late December interview, Isaacman said:

“My job now is to make sure that we can undertake such a transportation within the budget dollars that we have available and, of course, most importantly, ensuring the safety of the vehicle.”

My job now is to make sure that we can undertake such a transportation within the budget dollars that we have available and, of course, most importantly, ensuring the safety of the vehicle.

Jared Isaacman | NASA Administrator

That statement marked a clear shift in tone from earlier momentum behind the move. Isaacman acknowledged that cost overruns and preservation risks could prevent Discovery from being relocated at all.

Isaacman’s caution carries particular weight given his own background in spaceflight. Before becoming NASA administrator, he flew to orbit twice as a private astronaut, commanding the Inspiration4 mission in 2021 and later flying aboard SpaceX’s Polaris Dawn. He has personally experienced launch, microgravity, and reentry, and has spoken publicly about the risks inherent in spaceflight and the responsibility that comes with operating flight-proven hardware. Discovery is not a mockup or a replica. It is a flown spacecraft that endured the same forces Isaacman himself has experienced, multiplied across 39 missions. Understanding what it takes to safely send a vehicle to space should also mean understanding why a historic orbiter should be preserved intact once its flying days are over.

Isaacman also emphasized that the “One Big Beautiful Bill” does not explicitly require the spacecraft to be a Space Shuttle. If moving Discovery proves impractical, he said NASA could instead transfer a different flown spacecraft, such as an Orion capsule from the Artemis program, to Houston. Orion vehicles are routinely transported by truck and can be displayed without dismantling.

As of this writing in January 2026, no vehicle transfer has occurred, no funding beyond the initial authorization has been finalized, and no safe transport plan for Discovery has been approved.

Why Cutting Up Discovery Was the Wrong Idea

Thankfully, it appears that Discovery will remain intact after all.

Space Shuttle Discovery – like any of the other surviving shuttles – is not expendable. It is a national treasure. In America, we don’t “dismantle” national treasures in the name of politics. We preserve them.

Breaking up Discovery for transport would cause irreversible damage to a spacecraft that survived launch, reentry, and the most demanding operational environment imaginable. To dismantle it now, after decades of service and careful preservation, would permanently compromise its historical integrity.

The Smithsonian has made clear that Discovery is a cornerstone of its human spaceflight collection. Ongoing expansions at the Udvar-Hazy Center reinforce the museum’s long-term commitment to displaying the orbiter intact and accessible to the public.

Discovery flew every mission the Space Shuttle was meant to fly. It embodies the full arc of America’s shuttle era, from early optimism to hard-earned resilience.

For the foreseeable future, Discovery remains exactly where it should be. Fully intact, publicly accessible, and preserved as it last flew in 2011.

And that is not a failure of ambition.

It is an act of stewardship.