The fascinating reason why the legendary refueling wing still uses the “Square D” on their jets instead of a number.

As it is with most things in life, nothing comes to pass overnight. The outcome is usually the result of a series of linked events. If just one link in the event chain breaks, the outcome will likely be a non-event.

The iconic Square D tail code on the 100th ARW’s KC-135 tankers came to pass and endures due to an obscure, inauspicious event. It would be the starting point for a series of incredibly important links that would not become evident until many decades later.

A few months before World War I ended in November 1918, an ordinary dinner party for VIPs and politicians occurred at Gray’s Inn in London. There was no stated or unstated purpose for the party. Hindsight being 20/20, the party likely included informal conversations about the war and legislative issues.

Two gentlemen RSVP’d, both of whom were moderate VIPs and politicians combined. These gentlemen were Sir Winston S. Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR).

The dinner party the two future icons attended in 1918 had no memorable moments, yet it still served as their introduction. Neither man made any effort to contact the other throughout the 1920s and early 30s. There was one thing, however, that Churchill never forgot: they both served in political leadership over their respective navies. Their service would be relevant to the story many years later.

These two men greatly influenced the future of the United States as a superpower and military titan. With Great Britain being the only superpower before World War II and their experience in large-scale military mobilization on a global basis, it would be critical to America’s massive growth. The Square D tail code would come to pass as a small success story from these historic relationships.

Why Churchill?

In 1918, Churchill (and many others!) might have concluded that he had reached his “Peter Principle” comeuppance. The idea behind the principle is that professional workers get promoted up the ladder until they reach a career level they are not competent.

This hard assessment stemmed from a 1915 war strategy decision concocted by Winston Churchill. He was a member of the House of Commons and held one of the top five most important prime minister appointments, First Lord of the Admiralty—the equivalent of the Secretary of the US Navy.

If any aspect of conducting war by Great Britain set them apart, it was the Royal Navy. The number one way the British projected strength and commercial success around the world was the Royal Navy. In Churchill’s mind, this meant that the Royal Navy was the most critical conveyance of projected power in times of war. The Royal Navy was the military glue that held the Empire together.

Seeking to support the British Army by relieving strategic pain points, Churchill convinced the War Cabinet that a second front to pressure Turkey, Germany’s ally, was needed. The goal was to seize control of the Dardanelles, the Bosporus Strait, and the Black Sea.

Churchill planned to use the Royal Navy and an Allied Army of troops from France, Great Britain, Australia, and a few lesser forces to land on the Gallipoli Peninsula and then move north to the Dardanelles choke point.

For followers of World War I History, we know the outcome of the Gallipoli Campaign: it was an Allied disaster on the water and the land. They completely underestimated the Turks at every turn. To make matters worse, the British were shocked upon the discovery of the enemy’s use of submarines; several ships were lost.

Tactically, the Allies and Turks both had 250,000 casualties each. But it was a costly, strategic failure for the Allies. The area in and around the Dardanelles remained solidly under Turkish control.

The Gallipoli disaster fell squarely in the lap of Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill was forced out of his War Cabinet role. He remained a Member of Parliament (MP) but took a leave of absence to reactivate his British Army commission and report to the Western Front in France.

After serving for a year on the front lines in France, he returned to his seat in Parliament. Churchill clamored for a high-level cabinet position. His first cabinet ministry commenced in 1908 under his friend, Herbert Asquith. However, an election put David Lloyd George in the prime minister’s chair; he was not in the same political party as Churchill.

Lloyd George had no interest in putting Churchill in a senior cabinet job. From 1916-1922, Lloyd George posted Churchill to several lower ministries, ostensibly to keep him away from 10 Downing Street. In 1922, Stanley Baldwin, the new Prime Minister, brought Churchill back from his low-level assignments and made him Chancellor of the Exchequer (similar to the US Treasury Secretary) until 1929.

When a new Prime Minister took office in 1929, Churchill expected to be replaced as Chancellor of the Exchequer. However, he was surprised that he wasn’t offered any position at all—not even a minor role. Although he remained a Member of Parliament, the Prime Minister gave him no official responsibilities. It would be another ten years before Churchill returned to a cabinet post.

Why Roosevelt?

Churchill saw his political fortunes peak as First Lord of the Admiralty but felt he was mired in a political slump when he had his chance encounter with FDR at the dinner party. On the other hand, Roosevelt was eight years younger and a rising political star. Throughout the Wilson Administration, Roosevelt was the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. The 1920s and beyond looked very promising for FDR. What happened instead sidelined him for the decade; he developed a severe case of polio.

Even though FDR came from an old, monied family and sought the best doctors, he would never walk unaided again. He had no idea what the future held for him, but he was not quitting.

Although some geopolitically savvy people like Churchill and Roosevelt could see trouble brewing in the future, neither man could foresee their leadership role in the struggle to come or the importance of their growing friendship.

The dinner party attended in 1918 by the two future icons may have been for no particular purpose, but it served as the starting point of a historical relationship.

The 1930s Arrive

Although it did not register with FDR until the 1930s, a country does not become the sole superpower in the world as the United Kingdom did, without the largest navy, a professional army, a strong industrial base, a mature higher education system, a deeply experienced scientific, research and development community, an unparalleled geopolitical and diplomatic core located in every corner of the world, a global, full-time, seasoned, successful, and skilled intelligence collection & espionage apparatus since the 1890s, and lastly, the muscle memory to implement a large military logistics and war mobilization program.

How did the United States measure up compared to the British capabilities worldwide? Although the US had some capabilities to varying degrees, none exceeded the U.K.’s level of competency. The idea that the United States was ready to assume the mantle of the world’s “Arsenal of Democracy” was still many years away. Fortunately, Winston Churchill understood all of this quite well and reasoned that he needed to cultivate America and her new President at some point down the road.

The Rise of Hitler and Nazi Germany

Winston Churchill was well-educated, well-traveled, and a shrewd judge of character. Just because he was relegated to the “backbench” in the House of Commons, with no portfolio of duties from the Prime Minister, did not mean he was disinterested in affairs of state. In short, you could take the boy out of geopolitics, but you could not take geopolitics out of the boy.

As far as Winston Churchill was concerned, a constitutional monarchy with a well-developed system of colonies was the best form of government. A constitutional democracy like the United States had its uses, but he could not be too harsh about the US because, after all, his mother was an American.

Other forms of government, however, such as totalitarianism, dictatorships, Nazism, Fascism, and Communism, were scourges to Churchill. He was wary and had a deep distrust of the likes of Josef Stalin and the rise of Nazism led by Adolf Hitler. Unfortunately, no one at 10 Downing Street or Buckingham Palace was overly interested in the assessment from a supposed washed-up geopolitician.

In 1922, Italy became a Fascist dictatorship under Mussolini. Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931. By January 1933, the Nazis had secured enough seats in the Reichstag for Hitler to be appointed Chancellor. Around this time, Winston Churchill believed it was time for America to begin confronting the shifting global landscape. He set out to engage the new US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Private Communication Between Two Former Naval Persons

Churchill pondered the what-ifs of another world war. Great Britain was the only superpower in 1914. When World War I ended, the British Empire had lost 886,000 sailors and soldiers. Injuries accounted for an additional one million men.

The total number of British wounded and dead equaled 12.5% of the entire country’s population of men, women, and children. It was a well-known fact that after three years of war, the British Army was running out of military-age men to recruit or draft. And finally, the financial cost incurred by Great Britain during the war nearly bankrupted the country.

It was crystal clear to Churchill that if another world war befell Great Britain, she would be fighting it alone and ultimately defeated. In Churchill’s learned opinion, the free world would likely not survive if the Americans did not enter the war, or belatedly, after three years of fighting, as it was in World War I.

The correspondence between Roosevelt and Churchill is archived and preserved in more than a dozen known worldwide repositories. It is so voluminous that calling it massive would be an understatement. These holdings include official documents and some of the private, personal letters between the two men.

Official correspondence between FDR and Churchill started within days of Germany’s September 1939 invasion of Poland. This communication was permissible because both leaders were in senior government leadership positions, as President and First Lord of the Admiralty.

However, informal, private communication started in 1934. This communication between a sitting President and a House of Commons backbencher would have been scandalous if it had leaked to the public. Churchill was the first to send a handwritten letter to FDR. He initiated the practice of greeting each other with “From one naval person to another naval person.” The letters were written as opinions and not official government policies and plans.

Churchill covered the geopolitical issues of concern. Roosevelt discussed the American public’s desire to stay out of foreign wars. Eventually, the letters covered the US Congress’s series of neutrality laws passed in the 1930s, and the difficulty of providing security assistance to Allied countries engaged in conflict.

When the Churchill/Roosevelt communication became official in 1939, their private correspondence had put the two men on the same page, saving valuable time when war broke out.

Communications After Churchill Became Prime Minister

America’s neutrality laws began to be repealed in bits and pieces starting in September 1940, with most of the laws rolled back by March 1941. At this point, Great Britain and the United States slowly started exchanging military liaison officers to become familiar with each other’s military capabilities, industrial sector, and methods for military service induction and training.

Learning from each other was the right thing to do, but the liaison efforts were limited until America formally entered World War II in December 1941. High-level meetings in 1941 developed the plan to focus on wresting control of Europe from the Nazis and Italian Fascists as the first major goal. This agreement came to be known as the Atlantic Charter.

Churchill, Roosevelt, and Their Combined Chiefs of Staff’s First Actions

America’s initial war activities in 1942 were totally focused on quickly obtaining military equipment and training soldiers, sailors, and airmen to deploy to the European Theater of Operations (ETO). Naturally, the arrival of American help could not come fast enough for the British.

One of the greatest concerns conveyed by Churchill and his military chiefs was making sure that everything needed for America to fight dovetailed together in the ETO. Simple examples of British concern included having airmen in the ETO but not enough planes to fly, or vice versa, or having enough planes but a limited supply of bombs.

The US logistics effort to move men, materiel, and machines in a choreographed manner was an iterative process throughout the war. It required 24/7 vigilance and communication between all parties. The Square D tail code’s genesis is an outgrowth of America’s choreographed logistics effort.

The Details of the Square D Story

When the US Army Air Force began its preparations for mobilization and deployment to the ETO, neither the British nor the Americans had any valid information to predict how many men, machines, and munitions would be needed to fight the war. Comparing prewar and postwar aircraft inventory data shows that by the war’s end, the Air Force had over 10 times as many planes as before the war.

It was clear that to produce that many planes, the Air Force had to keep the factories running 24/7/365 until they were told to stop. It was understood that everyone involved in military induction, capital equipment (e.g., planes, ships, tanks, etc.) acquisition, and munitions manufacturing had to remain focused on their work and keep a careful record of everything.

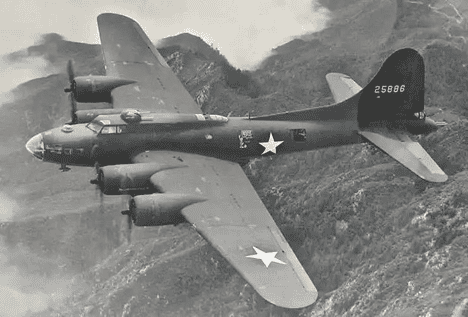

As the planes rolled off the assembly lines (that is correct, plural, Lockheed and Douglas Aircraft built B-17s under license), the Air Force had to orchestrate what happened next. They had to decide where to send them and which organization was the new owner. This process seems relatively tame on the surface, but with all aspects of the military expanding at a prodigious rate, it was not easy.

An example of the Air Force’s efforts to keep pace with the expansion was a gaggle of newly produced B-17 Flying Fortresses from Boeing in Seattle, WA. The planes were flown to Walla Walla Army Air Base, WA, in November 1942, where a newly formed unit took ownership. The unit and its aircraft would change bases five more times stateside before deploying to the ETO in June 1943!

The Air Force’s Expanding Organizational Structure

The Air Force entered World War II with the same structural components as today. Starting at the bottom: squadron, group, wing, air division, numbered air force, and command. During the war, Air Force Headquarters decided that the primary building block would be the “group” commanded by a full colonel. A lieutenant colonel would lead squadrons. However, wartime exigencies often required flexibility, and it wasn’t uncommon for a group to be led by a lieutenant colonel and a squadron by a major.

One of the biggest problems the Air Force dealt with (and not very well!) during the war was assigning unit numbers. Unit numbers were ordinarily managed very meticulously by Air Force Headquarters. The war expansion forced HQ to delegate new unit activations to the numbered air forces two levels below.

To exercise some semblance of control, HQ issued procedures for use by the numbered air force’s S-3 operations staffers. Each S-3 staff was assigned a large block of unit numbers to use.

This workaround unit activation process created an unforeseen glut of unit numbers for wings and below. It became common practice to issue new numbers for not only unit activations but also deactivated units being reactivated or transferred. It was much easier for S-3 shops to use new numbers instead of reusing numbers from deactivated units.

Although Air Force headquarters would reclaim its provenance over unit numbering after the war, the process did not change. An attempt to overhaul it in the 1950s only added to the confusion, creating a surplus of unit numbers and severing ties with previous awards and decorations. These issues weren’t fully resolved until 1966.

Activating the Unit that Would Receive the Square D Tail Code

The US Army Air Force activated the 100th Bombardment Group (Heavy) in June 1942 at Orlando Army Air Base, FL. The 100th was originally slated to get Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers. However, this changed to B-17s when the 100th arrived in Walla Walla, WA.

The 100th BG group was assigned four squadrons: the 349th Bombardment Squadron, 350th Bombardment Squadron, 351st Bombardment Squadron, and the 418th Bombardment Squadron.

After the 100th BG arrived at Walla Walla, it received the first four B-17 Flying Fortresses from the Boeing factory in Seattle, WA. Crew training started immediately, and they began deployment preparations for England in April 1943.

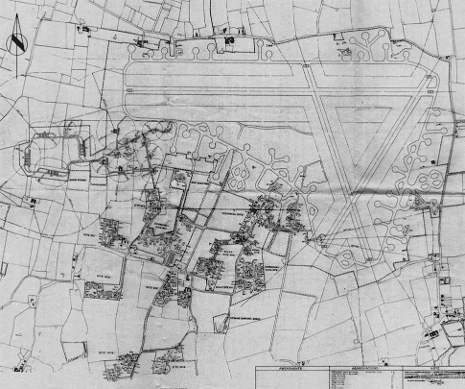

The Army Air Force continued to follow Royal Air Force advice on how to apply unit identifications. Using tail codes based on a unit’s home base was of no value because of the dozens of airfields used in England, and it was information no one wanted the Germans to have.

The solution was to have deploying groups use lettered tail codes. The first bomb group to depart stateside carried the Square A tail code. This meant something to American airmen, but it didn’t mean much in terms of useful intelligence for the Germans.

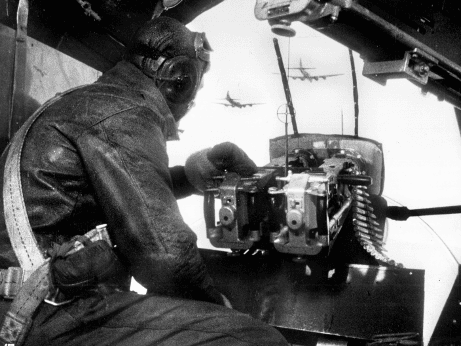

Little did the deploying bomber crews know that the huge, lettered tail codes would be invaluable during combat sorties in sorting out which planes belonged to which group. No one realized until they started flying combat sorties that a mission with more than 100 B-17s in formation was commonplace.

Anytime an air crewman spotted a large, lettered tail code in the air, it was a comfort to know they were with the right group of planes. It was left unstated, however, that the big tail codes also helped identify a B-17 that had been hit and was not likely to make it home.

The 100th Bomb Group Deploys to the ETO

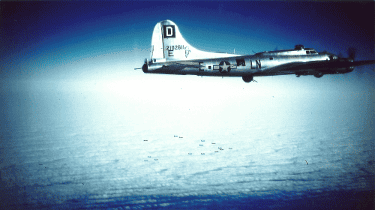

The 100th deployed as the fourth group simultaneously with three other B-17 groups. The 100th was assigned the Square D tail code.

The 100th ground troops departed in early May 1943 on the Queen Elizabeth, and the aircrews departed in late May in their B-17s on the North Atlantic flying route. All elements of the 100th BG were in place by 9 June 1943 at Thorpe Abbots Army Airfield, number 139. Thorpe Abbots was the home base for the 100th until the war ended.

About two weeks later, the 100th flew its first combat mission against the submarine pens in Bremen, Germany. This raid was the starting point for the legacy of the “Bloody Hundredth, ” depicted in the 2024 miniseries Masters of the Air. Click the link for an informative podcast.

The 100th’s first mission claimed three B-17s from the 349th Bomb Squadron; no one survived. All told, the group lost 182 B-17s throughout the war, which was double the number of planes it had when it reported to Thorpe Abbots on 9 June 1943.

Coming to grips with the loss of 182 aircraft is hard enough. The human toll is even worse. The 100th BG started with 960 crewmen. Over 800 were killed in action, and 950 were captured and spent the rest of the war in a POW camp.

The 100th gained the Bloody Hundredth sobriquet from other groups due to its large losses. By war’s end, the losses were not much more than any other group’s, but their losses were infamous for the circumstances in which they transpired.

The 100th BG flew the disastrous (for the Allies!) raids on Schweinfurt, Regensburg, and Bremen. Typical 100th losses on these raids were 12 of 13, 13 of 15, and nine of 12 aircraft.

Another tough run for the 100th became known as “Black Week,” October 8-14, 1943. On 10 October, they put up 18 B-17s on a mission against Munster, Germany. Only one B-17 returned from the raid, with two engines out and two of its airmen seriously wounded.

The tale of the Bloody Hundredth staggered through 1944 with the same sobering results. The group flew its last combat mission in April 1945.

The 100th Bomb Group’s Legacy

During the 100th’s 22 months of combat, it flew 306 missions (some more than just a single out-and-back) and was credited with 8,630 sorties. It had more ETO flying hours and sorties than any other bomb group. The group dropped nearly 20,000 tons of bombs and 435 tons of humanitarian supplies.

The group’s gunners shot down a confirmed 261 German planes, with 1,010 probable and 139 possibly destroyed.

The accolades of the 100th Bombardment Group include:

- Distinguished Unit Citations:

- Germany, 17 August 1943

- Berlin, Germany, 4, 6, and 8 March 1944

- French Croix de Guerre with Palm:

- 25 June to 31 December 1944

- 25 June to 31 December 1944

- Service Streamers:

- Air Offensive, Europe

- Normandy

- Northern France

- Rhineland

- Ardennes-Alsace

- Central Europe

- Air Combat

The Post-War Period and the 100th Bomb Group

The Bloody Hundredth returned to the US and was deactivated in December 1945 at Camp Kilmer, NJ.

History will show that the 100th was one of the first four bomb groups to deploy to England, and it was the last one to come home.

Air Force headquarters issued policies governing the process for units and aircraft returning stateside. Any unit that was going to fly their planes home had to remove all non-regulation markings or those applied due to ETO operations. These policies meant that ad hoc nose art and tail codes had to be removed. Naturally, the airmen were more upset about removing the nose art than the tail codes!

When the 100th was preparing to go home, the 8th Air Force held firm that the B-17’s nose art had to be removed. The group was allowed to fly home with the Square D tail code intact. The 8th Air Force saw this waiver as a nod of honor for the achievements of the last bomb group to fly home.

The 100th BG was dormant for less than two years when it was reactivated as a unit of the Air Force Reserve in May 1947 at Miami Army Airfield, FL. The reactivation coincided with the Air Force separating from the Army to become a standalone service branch.

The separation from the Army allowed the Air Force to stand up its own reserve component. In the case of the reactivated 100th Bomb Group, they were assigned to be the Formal Training Unit for the Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

After the war, the Air Force adopted a practice of linking past honors to current unit members. This meant that future members of the 100th were expected to wear the Distinguished Unit Citation and French Croix de Guerre ribbons earned during World War II. I served in the 100th during the Vietnam era when its mission had shifted to strategic reconnaissance, and I always wondered why we were wearing ribbons awarded 25 years earlier.

As for the 100th’s Square D tail code, its return came with an odd twist. When the unit was reactivated, the new commander–whose identity remains unclear due to a lack of accessible records–authorized the Square D to be painted on the worn-out B-29s being delivered.

In any case, the mystery commander’s decision to reactivate the Square D tail code was allowed to stand and has been a source of pride for airmen assigned to the 100th ever since. In a nod to the maintenance of unit history, the Square D tail code is now proudly carried by the 100th Air Refueling Wing based out of RAF Mildenhall, England.

It’s worth emphasizing that no other reactivated bomber group was permitted to display its original tail code. This singular honor belonged only to the 100th Bomb Group.

The 100th BG’s B-17s, airmen, and the Thorpe Abbots Airfield may be gone, but the accomplishments live on in the iconic Square D tail code proudly displayed on the 100th ARW’s KC-135 Stratotankers.

The entire US military has been, and still is, standing on the shoulders of giants for 250 years. The bond of America’s troops will never be broken.

Being a fourth-generation American service veteran, I remember my great-grandfather’s admonishment when I joined the Air Force. He spoke about carrying forward the torch of selfless service. He then said, “…and don’t drop the damn thing!” I did not drop it, and neither has any of the 100th’s alumni in the past 83 years.

The Square D: a fitting tribute to the 100th Bomb Group and its future successors.