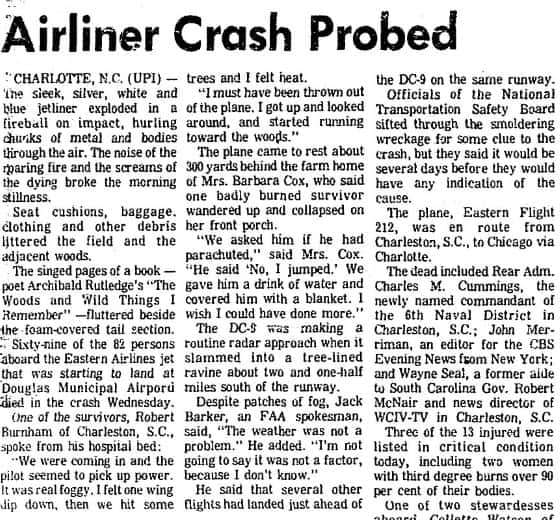

Pilot error, complacency, and distraction, coupled with obscuring fog at the most critical point of flight, resulted in the crash of Eastern Air Lines Flight 212, a DC-9-31, on 11 September 1974, and were instrumental in the adoption of new cockpit rules.

The Setup: Crew, Aircraft, and a Short Hop North

THE AIRCRAFT

Both manufactured and delivered on 30 January 1969, the aircraft, registered N8984E, underwent its last block overhaul at the carrier’s Miami, Florida, maintenance facility five years later, on 7 January 1974.

THE FLIGHT CREW

Eastern Air Lines Flight 212 was flown by two cockpit crew members and attended to by two cabin attendants.

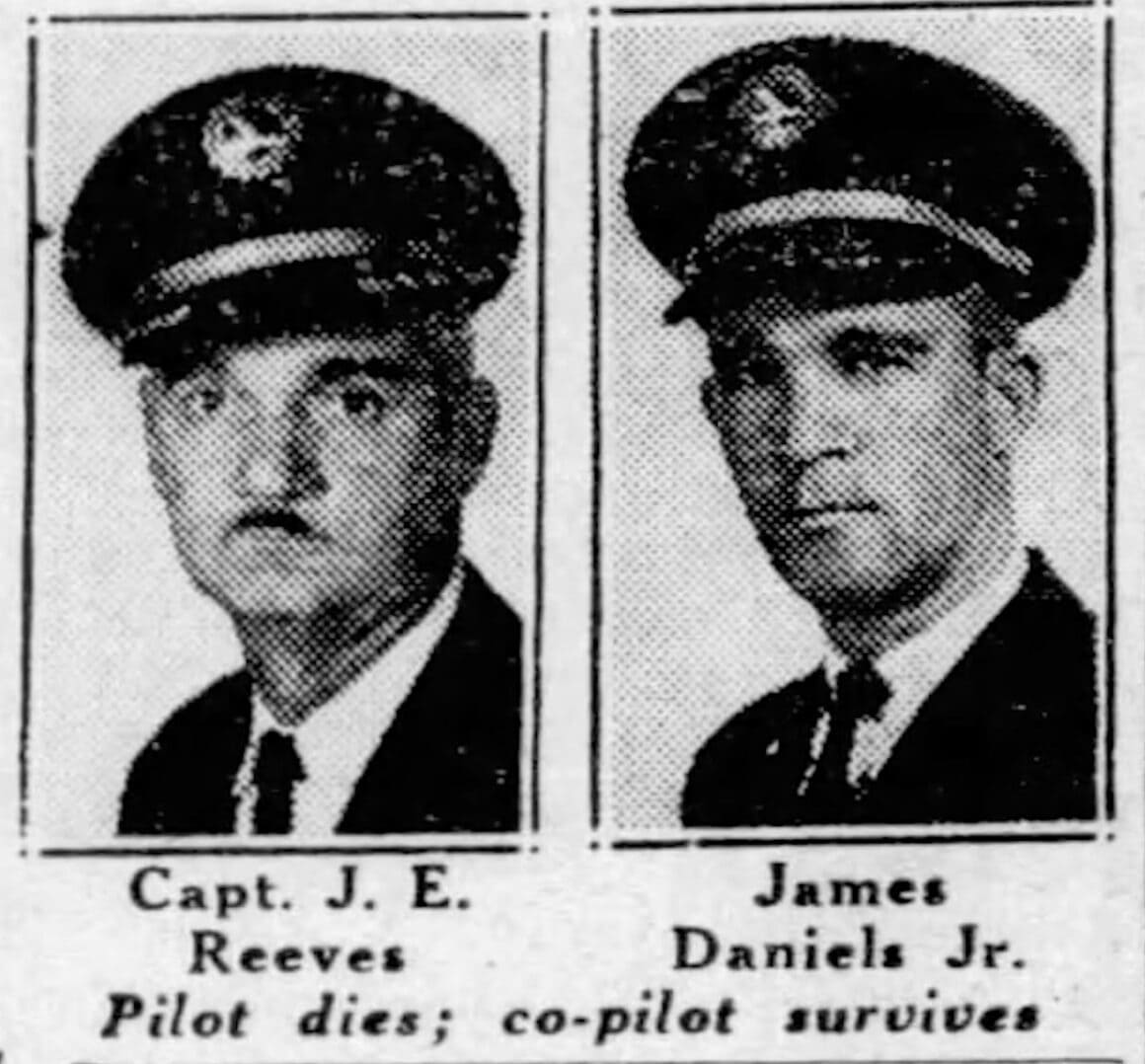

Of the former, Captain James E. Reeves, 49, held type ratings on the Convair 240, 340, and 440, the Lockheed L-188 Electra, and the Douglas DC-9, and was hired by Eastern on 18 June 1956. He had accrued 8,876 hours as plot-in-command, of which 3,856 were on the DC-9, whose type rating he had achieved on 14 December 1967. His last proficiency and line checks had respectively occurred on 25 April and 8 August, both in 1974. He had had a 13.5-hour rest period before he reported for duty for Flight 212.

He was assisted by First Officer James M. Daniels, Jr., 36, who had been hired by Eastern on 9 May 1966. He held a commercial pilot certificate with multi-engine and instrument ratings. Of his 3,016 hours logged, 2,693 had been in the DC-9. Unlike Reeves, he had had considerable rest before reporting for duty—in this case, a 61-hour total.

Of the two flight attendants, Collette Watson had been hired by Eastern on 11 September 1969 and received her last recurrent training six years later, on 29 July; Eugenia Kerth, who had been hired on 7 January 1970, received her own last recurrent training four years later, on 17 January.

A FERRY FLIGHT FROM ATL TO CHS

The four crew members ferried the aircraft from Atlanta, Georgia, to Charleston, South Carolina, with 17,000 pounds of A-1 jet fuel on board, of which 5,000 were required for the empty sector. The DC-9 had accrued 16,860.6 hours up to this time and was within both its gross weight and balance limits for the flight.

After the ferry flight, the plan was to fly from Charleston to Charlotte, North Carolina, and Chicago-O’Hare International Airport in Illinois.

DEPARTURE FROM CHARLESTON

The DC-9 was fueled with 17,500 pounds of A-1 jet fuel, of which 4,500 were required for the 150-mile, 30-minute segment to Charlotte. With 78 passengers planned for the flight, the DC-9-31 was prepared for its departure. The flight crew, called clearance delivery before their actual pushback, were instructed to turn right after takeoff and intercept the Victor 53 airway, then climb and maintain 3,000 feet until they reached a point 30 miles DME, or distance measuring equipment, north of Charlotte. They were told to expect clearance to their assigned, 16,000-foot altitude. The pilots would contact departure on a frequency of 119.3 and use “1000” as its transponder code, which would appear on radar screens as soon as the cockpit “Ident” button had been pressed.

Although they were offered both Runways 12 and 33 for takeoff, they chose the former. The wind was almost nonexistent, blowing at three knots from 360 degrees with an altimeter setting of 30.12 inches of mercury.

The air speed bug was moved to the 135-knot position, the calculated takeoff speed based upon the aircraft’s gross weight; the jet was configured to 15 degrees of flaps; and the stabilizer trim knob was set to a position between the “five” and the “six.”

First Officer Daniels would be the pilot-flying and Reeves the pilot-not-flying on the next flight.

The jet was instructed to “taxi into position and hold.” aircraft N8984E paused on Runway 12’s threshold, while the final TakeOff Checklist was completed. Tower cleared the Dc-9 for takeoff, “Two twelve rolling” replied Reeves. It was 07:00.

A temporary toe brake restraint after throttle advance enabled the Pratt and Whitney JT8D turbofans, mounted on the aft fuselage sides, to spool up. The crew verified by the center cockpit panel N1, EGT (exhaust gas temperature), N2, and fuel-flow instruments as the jet spooled up.

Thundering through its V1 (go/no-go) and VR 128-knot rotation speeds, Daniels pulled on the yoke and the jet lifted off the runway. First with a nose wheel disengagement, and then the DC-9 peeled its main wheels off the ground.

Maintaining a 210-degree heading as it established a positive climb rate, it retracted its tricycle undercarriage and, with sufficient speed, its trailing edge flaps. Assuming its maximum climb power, its EPR (engine pressure ratio) was set to 196.

After its contact with departure, Eastern Air Lines Flight 212 was instructed to “climb and maintain seven thousand.”

En Route: Nothing Unusual, Until the Fog Took Over

Its relatively short flight plan entailed a 33-mile northwesterly sprint, an 81-mile north-northwesterly one to Columbia, and a final 85-mile northerly one to Charlotte via Victor 53, Victor 37 to a radio navigation station 20 miles south of Charlotte, and ultimately a straight one to its destination.

No longer requiring the increased wing camber achieved with its high-lift devices, Eastern Air Lines Flight 212 retracted its leading-edge slats at 180 knots.

Already cleared to 16,000 feet, the DC-9-31 now climbed out of 7,000, instructed to proceed direct to Fort Mill and contact Jacksonville Center on a frequency of 127.95, which in turn gave it a transponder code of “1100.” The “Ident” button was once again pressed so that it could be uniquely identified by it.

Shallowly ascending through 15,300 feet at a 500-foot-per-minute rate, it attained a 325-knot ground speed.

Since there was no time for catering on the short sector, the flight attendants swept through the coach cabin with trays of coffee cups.

Down Into the Murk: The VOR Approach to Runway 36

THE APPROACH TO CHARLOTTE

Eastern Air Lines Flight 212 was handed off to Atlanta Center on a frequency of 127.15, which instructed it to descend and maintain 8,000 feet. The pilots set field elevation.

The aircraft would dock at Gate 5 and take on the maximum allowable 20,000 pounds of fuel for the longer segment to Chicago.

RUNWAY CHANGES AND WEATHER COMPLICATIONS

After it contacted Charlotte Approach Control on 124.0, it was instructed to turn to a 040-degree heading. While the crew was given a choice of runways at Charleston, there would be no option at Charlotte.

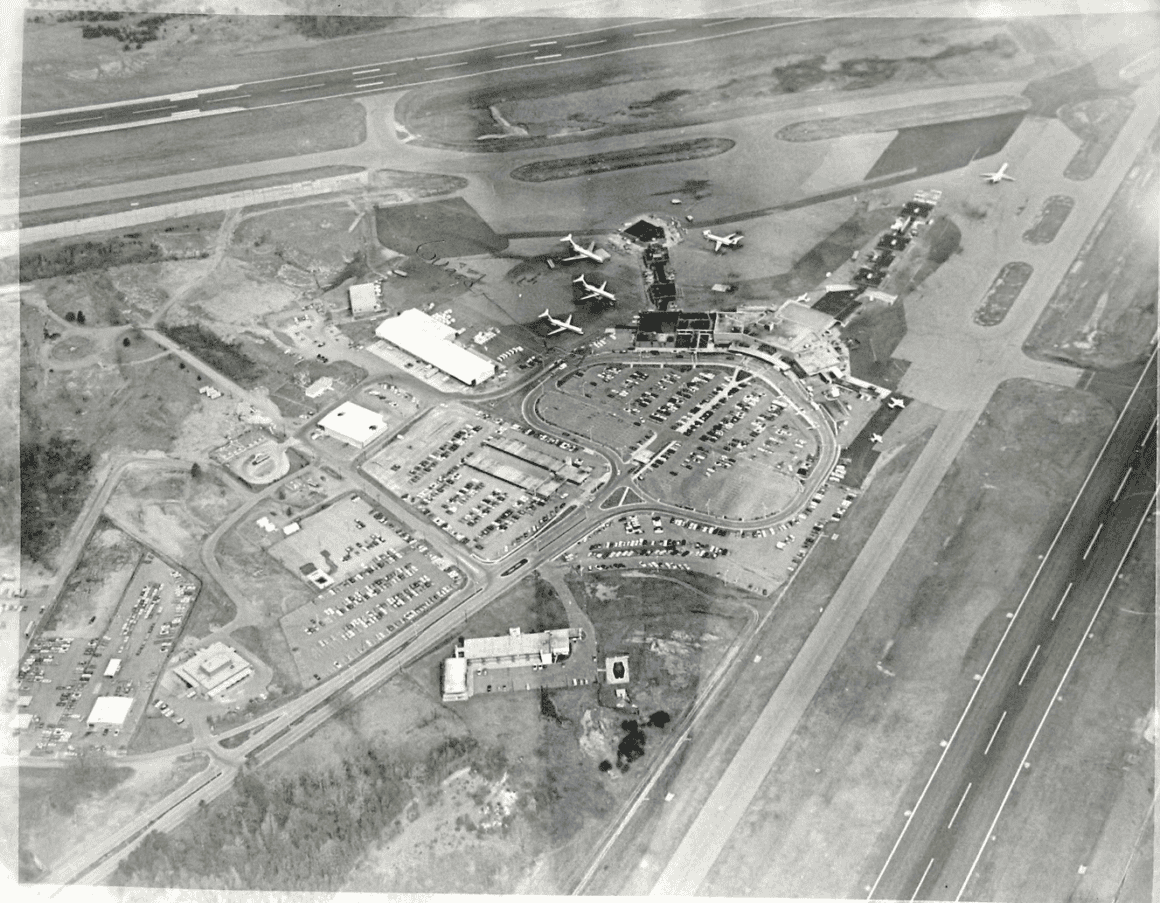

To facilitate capacity expansion at what was then known as Douglas Municipal Airport, a second north-south runway, parallel to the existing Runway 5, was being constructed. Because its southern end extended through the approach lights, which themselves stretched 2,000 feet beyond its threshold, the options for an instrument approach that day were limited.

The morning fog from the nearby Catawba River, now collecting over and obscuring Runway 5, mandated a switch to Runway 36 and its nonprecision VOR approach.

“VOR Runway 36 approaches in use,” advised the latest “information uniform” automatic terminal information service (ATIS) recording. “Landing and departing Runway 36. All arriving aircraft make initial contact with Charlotte Approach East on 124.0.”

It also advised of the potentially obscuring conditions: a partially obscured sky, broken ceilings at 4,000 and 12,000 feet, a 1.5-mile visibility, a 67-degree Fahrenheit temperature, wind out of 360 degrees at five knots, and ground fog.

VECTORS, SPEED CONTROL, AND DESCENT PLANNING

Eastern Air Lines Flight 212 was instructed to “descend and maintain 6,000.”

Based upon its 4,500-pound fuel burn off, which gave the aircraft a 90,000-pound landing weight with 13,000 pounds still in its tanks, and a 21-percent center-of-gravity, the DC-9-31 would have a 122-knot VREF speed.

The Descent and In-Range Checklist, which was now complete, included items such as seatbelt sign illumination, fuel boost pump operation, setting the air conditioning and pressurization, and checking the hydraulic pumps. It preceded a Z-shaped vector, which initially required a left turn to a 360-degree heading.

Sufficient speed bleed-off permitted a five-degree extension of the trailing edge flaps.

Now descending through 7,000 feet for 6,000, the crew was instructed to turn further left to a 240-degree heading and, subsequently, to descend and maintain 4,000 feet. A further speed reduction facilitated a 15-degree flap extension. It now contacted Charlotte Approach Control on a frequency of 119.0.

“Eastern 212, continue heading two four zero,” was the approach controller’s instruction. “Descend and maintain 3,000.”

In order to increase the spacing between it and Delta Flight 608, which was now 3.5 miles from the Ross intersection, Flight 212 was required to reduce its speed—in this case, to 160 knots.

The Delta aircraft was further instructed to turn left to a 010-degree heading and was cleared for the VOR approach to Runway 36, while the Eastern DC-9, now six miles from that intersection, was instructed to turn right to 350 degrees.

ALTIMETERS AND THE RISK OF MISINTERPRETATION

As with any aircraft, altitude accuracy was tantamount to clearing obstructions, whether issued by an air traffic controller or noted on standard instrument departure (SID) or standard arrival route (STAR) charts.

Eastern’s DC-9-31s were provisioned with two types of altimeters.

The first, the drum-pointer type, obtained its readings from the air data computer, which was set by the barometric pressure at each airport. Comprised of a turning hand, which measured hundreds of feet, and a number display that indicated thousands and tens of thousands of feet, it could be easily misread. If half of a “3” and half of a “4” were visible, for instance, it indicated a 3,500-foot altitude.

The second altimeter, a counter-drum-pointer type located only on the lower portion of the captain’s instrument panel, more precisely recorded the barometric pressure outside the aircraft and transformed that measurement into a reading. The greater the atmospheric pressure became, the lower was the resultant altimeter reading, since air density decreased with altitude.

Comprised of a rotating head, which indicated hundreds of feet, and a window that displayed thousands (1,000) and ten thousands (10,000) of feet in digits. It was less likely to be misread, but its location made it difficult for the first officer to do so.

A CASUAL COCKPIT AT A CRITICAL MOMENT

Aside from the continued potential of an altimeter misread, the cockpit crew engaged in personal banter during a critical flight phase.

“During the descent, until about two minutes and 30 seconds prior to the sound of impact, the flight crew engaged in conversations not pertinent to the operation of the aircraft,” according to the National Transportation Safety Board’s (NTSB) final report. “These conversations covered a number of subjects, from politics to used cars, and both crewmembers expressed strong views and mild aggravation concerning the subjects discussed. The Safety Board believes that these conversations were distractive and reflected a causal mood and lax cockpit atmosphere, which continued throughout the remainder of the approach and which contributed to the accident.”

Although Charlotte Approach provided clearances, the cockpit crew was still responsible for its vertical guidance, since the nonprecision VOR approach did not provide the vertical and horizontal parameters that an ILS approach with its three-degree glideslope did.

In this case, the DC-9’s VOR receiver did exactly that—namely, receive the Charlotte VOR radio signal emitted by the VOR itself, which was located at the end of Runway 36, enabling the aircraft to follow the 353-degree compass heading to the touchdown point.

MINIMUMS, MISSED APPROACH CRITERIA, AND LOST AWARENESS

According to the approach plate, aircraft were required to cross the Ross intersection, which was located 5.5 miles (DME) south of the runway. However, its minimum descent altitude, or MDA, required it to maintain at least a 1,800-foot altitude above sea level and continue to do so until and unless the runway was visually discernible ahead. If not, they were required to execute a missed approach, which, as per the approach plate, instructed them to “climb to 2,300 feet, make a left turn via the outboard R-229 Charlotte VOR to the York intersection (20.0 DME), or as directed.” They could then attempt the approach again once cleared to do so or fly to a flight plan alternate.

The DC-9, now ten miles from the airport and advised to resume its no-longer-needed to slow for spacing. They were instructed to contact the Charlotte tower on 118.1. It was number two to land.

Subsequently cleared to land, it could descend to the 1,800-foot MDA (1,074 feet above ground level) until passing Ross and intercepting the 353-degree radial to the Charlotte VOR.

Aircraft accidents often result from several factors that, while never anticipated, can lead to a devastating result. This is sometimes referred to as the “perfect storm.” Eastern Air Lines Flight 212’s version of the “perfect storm” began here.

“ALL WE GOT TO DO IS FIND THE AIRPORT”

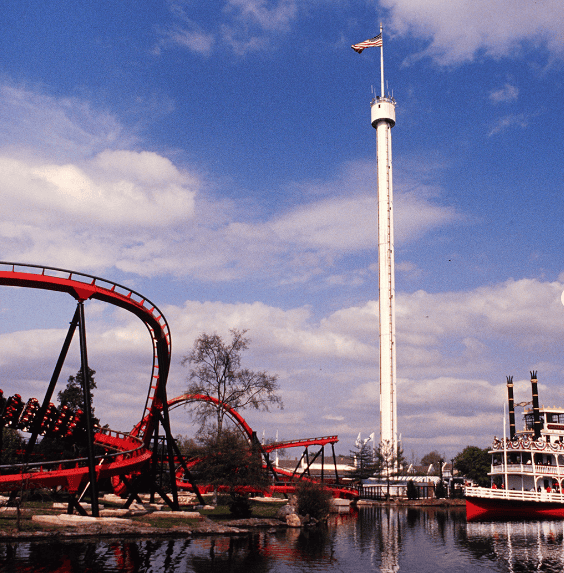

It plunged through fog, obscuring visibility, and the vectors the aircraft had been subjected to only increased the crew’s disorientation, as Reeves spotted a tower through his window that he believed marked the Carowinds Amusement Park outside of Charlotte.

“It was a strange sight, a startling apparition, protruding from the fog,” according to William Stockton in his book, Final Approach: The Crash of Eastern 212 (Doubleday and Company, 1977, p. 251). “It arrested their attention…The observation tower was unusual. They knew what it was. But it seemed to be in the wrong place in relation to their position after the radar vectors.”

That was because it wasn’t the Carowinds Tower.

Despite a terrain warning sound in the cockpit, it was ignored and silenced. And despite the belief that the aircraft was at 1,650 feet, it was actually at only 650 feet, because neither crew member had noticed the additional altimeter sweep, which would have indicated another 1,000-foot altitude loss.

Awaiting visual runway verification before the DC-9-31 could reinitiate its descent beyond the Ross intersection, the captain said, “Yeah, we’re all ready” at 07:33:52, according to the cockpit voice recorder. “All we got to do is find the airport,” to which Daniels replied, “Yeah.”

But they never would.

“The Blur of Trees”: The Final Seconds

TREES THROUGH THE FOG

Recoiling, applying full power, and pulling the yoke toward his stomach, Daniels desperately tried to extricate the airplane from certain impact the second the blur of trees appeared through the shroud of fog.

Senses and sensations, if any could penetrate, merged into a single, time-suspended void, created by the crashing, tearing, grinding, ripping, rupturing, screaming, wailing, shrieking, exploding, and disintegrating, and the silence of those who perished.

INITIAL IMPACT AND BREAKUP SEQUENCE

“The aircraft struck some small trees and then impacted a cornfield about 100 feet below the airport elevation of 748 feet,” according to the National Transportation Safety Board’s Aircraft Accident Report: Eastern Air Lines Douglas DC-9-31, Report Number NTSB-AAR-75-9. “It struck larger trees, broke up, and burst into flames. It was destroyed by the impact and the ensuing fire.

“At initial impact, the right wingtip struck and broke tree limbs about 25 feet above the ground. About 16 feet above the ground, the left wing struck and sheared a cluster of pine trees.

“The left main landing gear wheel struck the ground 110 feet past the initial impact point. The right main landing gear wheel struck the ground five feet farther down the field. The aircraft’s final descent angle was calculated to have been 4.5 degrees, and its bank attitude 5.5 degrees left wing down. The ground elevation was 620 feet. Wheel imprints were continuous for 50 feet and increased to a depth of 18 inches.

“Broken red glass from the lower fuselage rotating beacon was found within the tail skid and aft fuselage ground marks.

“As the aircraft continued 198 feet beyond the initial impact point, the left wingtip contacted the ground and made a mark 18 feet long.

FIRE, WRECKAGE PATH, AND FINAL RESTING PLACE

“After the aircraft had traveled 550 feet beyond the initial impact point, the left wing contacted other trees, and the wing broke in sections. At this point, ground fire began and spread in the direction of travel of the aircraft until the aircraft came to rest. The right wing and right stabilizer were sheared off.

“The remainder of the aircraft, the fuselage, and part of the empennage section continued through a wooded area. The fuselage breakup was more severe in this area.

“The aircraft wreckage came to rest in a ravine 995 feet from the initial impact point. The cockpit section came to rest on a magnetic heading of 310 degrees. The aft fuselage section came to rest at a magnetic heading of 290 degrees. The wreckage area was 995 feet long and 110 feet wide. No parts of the aircraft were found outside the main wreckage area.

“The nose landing gear was separated from the fuselage and was found in the extended position. The nose gear was not damaged by fire.

“The main landing gears were separated from their attach structure and were extended. The right main gear had been damaged considerably by fire. The left main gear received minor fire damage.

“The outer fan exit ducts of the front compressors on both engines showed evidence of rotational twisting in the direction of fan rotation. The fourth-stage turbine blades of both engines were intact and were not damaged. Neither engine casing had been penetrated. The thrust reversers of both engines were stowed.”

INSIDE THE CABIN

Sustaining two blows to her head, a punctured arm, and several lacerations, Senior Flight Attendant Collette Watson, the least injured, managed to extricate badly wounded First Officer Daniels, who had barely been able to unlock the cockpit door and crawl into the captain’s seat, through the narrow exit.

“Imagine the unreality of the terrible scene,” she recounted in Philip Gerard’s article, “The Courage to Fly” (Our State, 17 August 2021). “The aircraft you’re flying in has just slammed into fog-shrouded trees and broken apart, the nose shoved into a ravine. Fire suddenly erupts everywhere, people are screaming, and the front exit doors are blocked. Choking on thick smoke, you jerk on the cockpit door until the copilot is roused from shock and opens it…”

“Only a flight attendant stationed in the forward cabin was able to offer assistance to surviving passengers in escaping from the aircraft,” the National Transportation Safety Board’s Aircraft Accident Report: Eastern Air Lines Douglas DC-9-31, Report Number NTSB-AAR-75-9, continues. “The captain was killed by impact. The first officer and the flight attendant in the aft cabin received disabling injuries, which prevented them from aiding surviving passengers.

ESCAPE THROUGH THE COCKPIT

“A passenger and the flight attendant in the forward cabin assisted the first officer in making his escape. All three escaped from the aircraft through the left cockpit sliding window.

“The forward cabin doors were unusable because of obstructions and the attitude of the aircraft. No determination of the usability of the overwing exits could be made because of fire damage.

“The auxiliary exit through the tail was operable and, if it had been used, passengers could have cleared the fire area. The aft cabin flight attendant was probably unable to open the exit because of her injuries. The passengers in that area also may have been unable to open the exit, either because of their injuries or because they did not know how to operate the opening mechanism.

“Although the sliding window exit on the left side was the only cockpit exit used, the other cockpit window was usable.

FIRE, SMOKE, AND RESCUE RESPONSE

“All survivors reported that there was fire inside the cabin during the crash sequence. The insignificant levels of cyanide found in toxicological examinations indicated that the lethal factor was primarily the immediate, initial fuel fire. The effects of the fire were fatal to the passengers before the cabin interior materials had a chance to burn and generate a significant amount of cyanide gas. The fuel, which escaped from the ruptured tanks, ignited and moved along the ground with the aircraft wreckage. The fire was concentrated in the center fuselage area.

“The response of the fire and rescue equipment was timely. The firefighting and rescue activities were performed in an exemplary manner.”

A Partially Survivable Crash, a Brutal Post-Impact Reality

In the end, only First Officer Daniels, Flight Attendant Collette Watson, and eight passengers survived, while Captain Reeves, Flight Attendant Kerth, and 70 passengers either immediately or subsequently succumbed to impact and/or smoke inhalation incapacitation. Nevertheless, the NTSB cited three major factors that rendered the accident partially survivable:

- The occupiable area of the cabin was compromised when the fuselage broke up.

- The intense post-impact fire consumed the occupiable area of the tail section and the entire center section of the cabin.

- The occupant restraint system failed in many instances, even though crash forces were within human tolerances.

“The cockpit area and the forward cabin were demolished by impact with trees. The tail section, which included the last five rows of passenger seats, is classed as a survivable area. However, the post-crash fire created a major survival problem in this section.

“Bodies of most of the aircraft occupants were found outside two of the major sections of cabin wreckage, which indicates that the passenger restraint system was disrupted in these sections during cabin disintegration. The exception to the restraint system disruption was the tail section, where most of the occupants who survived the impact died in the post-crash fire.

“Only a small section of the cabin near the tail of the aircraft retained its structural integrity. Most of the structure was destroyed and, in most cases, the occupant restraint system failed. Finally, fire occurred in the cabin during the breakup of the aircraft and continued to burn until extinguished by the fire department.

“All survivors in the rear of the aircraft were either thrown out of the wreckage or escaped through holes in the fuselage. The surviving passenger and the two surviving crew members in the front of the aircraft escaped through a cockpit window.

“The forward cabin entry door was found partially open, but was blocked by a fallen tree. Because of the position of the wreckage, the ground blocked the forward galley door. The center fuselage overwing escape windows were destroyed by fire. The auxiliary exit in the tail of the aircraft was usable; however, it was not used for escape.”

A Lax Cockpit, A Missed Altitude, A Lasting Change

“The Safety Board was notified of the accident about 07:55 on 11 September 1974,” according to the NTSB report. “The investigation team went immediately to the scene. Working groups were established for operations, air traffic control, witnesses, weather, human factors, structures, maintenance records, powerplants, systems, the flight data recorder, and the cockpit voice recorder.”

It summarized the accident as follows:

“About 07:34 EDT, on September 11, 1974, Eastern Air Lines Flight 212 crashed 3.3 statute miles short of Runway 36 at Douglas Municipal Airport, Charlotte, North Carolina. The flight was conducting a VOR DME nonprecision approach in visibility restricted by patchy, dense ground fog. Of the 82 persons aboard the aircraft, 11 survived the accident. One survivor died of injuries 29 days after the accident. The aircraft was destroyed by impact and fire.”

First Officer Daniels later testified that Captain Reeves had failed to make the mandatory 500- and 1,000-foot altitude calls during the final approach, especially during deteriorating visibility conditions. Daniels himself believed that he was above 1,000 feet and only realized the altitude error “a split second prior to impact.”

“The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the accident was the flight crew’s lack of altitude awareness at critical points during the approach due to poor cockpit discipline in that the crew did not follow prescribed procedures.”

A direct result of the accident was the Federal Aviation Administration’s implementation of the sterile cockpit rule, which forbids crews from engaging in any activity, conversation, or otherwise between engine start and the reaching of a 10,000-foot altitude during departure and between that 10,000-foot altitude and engine shutdown at the aircraft’s destination during arrival.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Charlotte Observer produced an excellent write-up on the 50th anniversary of the crash of Eastern Air Lines Flight 212 in 2024. The 50th anniversary report can be viewed here (subscription required).