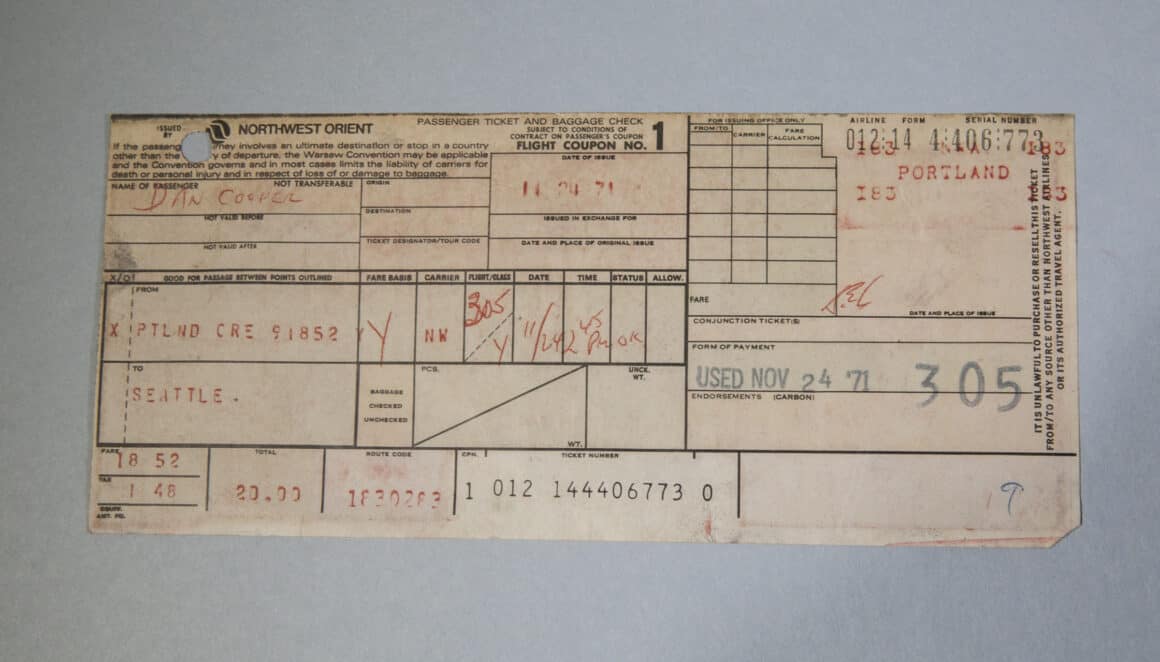

On a gloomy Thanksgiving Eve in 1971, a man in a black suit, thin raincoat, and clip-on tie paid $20 in cash for a one-way ticket. He walked onto a Boeing 727, took his seat near the back of the cabin, ordered a bourbon and a 7Up, and by the end of the night had become the most mythologized fugitive in modern aviation: the man the world calls “D.B. Cooper.”

It is a case so legendary that it manages to be both aviation folklore and a fully documented FBI investigation. And, in typical 1970s fashion, it comes with a bit of style.

Thanksgiving Eve at Portland International Airport

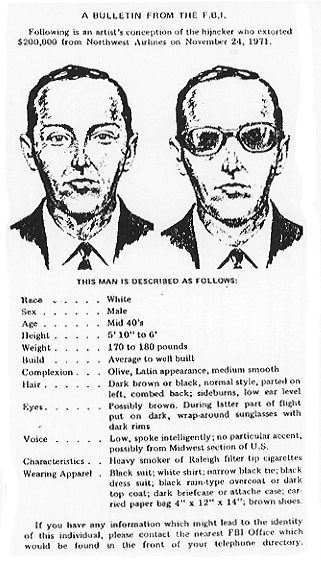

At approximately 1450 local time on 24 November 1971, a passenger identifying himself as Dan Cooper (the name D.B., which the world came to know, was the result of a mistake made by the media in the early days of the investigation) purchased a $20 one-way ticket from Portland International Airport (PDX) to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) on Northwest Orient Flight 305. Witnesses described him as a man in his mid-40s, around six feet tall, dressed like a business traveler who had opinions about briefcases and ties.

The airplane that day was a Boeing 727-100, tail number N467US, with only 36 passengers aboard. Evidently, holiday travel had not yet become the anxiety sport it is today.

Cooper’s seat was 18E. Close to the rear airstair. A detail no one thought much about at the time.

The Note That Was Not a Phone Number

Shortly after takeoff, Cooper passed a note to flight attendant Florence Schaffner. She did what many flight attendants in the early 70s likely did with unsolicited notes from men: she ignored it.

He leaned in.

“Miss, you’d better look at that note,” Cooper told her. ”I have a bomb.”

The handwritten message read in all caps:

“MISS – I HAVE A BOMB IN MY BRIEFCASE AND WANT YOU TO SIT BY ME.”

Cooper showed her what looked like dynamite sticks, wires, and a battery. Later analysis suggests they were flares.

He then delivered a calm shopping list of demands:

- $200,000 in non-sequential twenty-dollar bills

- Four parachutes

- A fuel truck waiting in Seattle

- No “funny business,” or he would “do the job.”

Schaffner relayed everything to the cockpit.

The Slow Circle Over Puget Sound

Captain William A. Scott informed passengers the plane had “minor mechanical difficulty,” an understatement of historic proportions, as Flight 305 began circling Puget Sound.

On the ground, FBI agents and Seattle police scrambled. Banks assembled 10,000 twenty-dollar bills. Every serial number was photographed in roughly three hours using Regi-Micro micro-perforation machines, a genuinely impressive feat in 1971.

Northwest Orient president Donald Nyrop authorized full compliance. Company policy: pay the ransom and avoid casualties.

At 1746 local time, Flight 305 landed at SEA and parked at a remote stand away from the terminal. Cooper ordered the shades closed and lights dimmed.

A suitcase containing $200,000 and four parachutes was rolled up on a baggage cart. Cooper released all passengers and all but one flight attendant, Tina Mucklow. She remained as the intermediary.

A Second Takeoff, a Strange Flight Plan

Cooper now ordered the 727 to fly to Mexico City with the following configuration:

- Flaps at 15 degrees

- Gear down

- Cabin unpressurized

- Altitude below 10,000 feet

- Airspeed at or below 200 knots

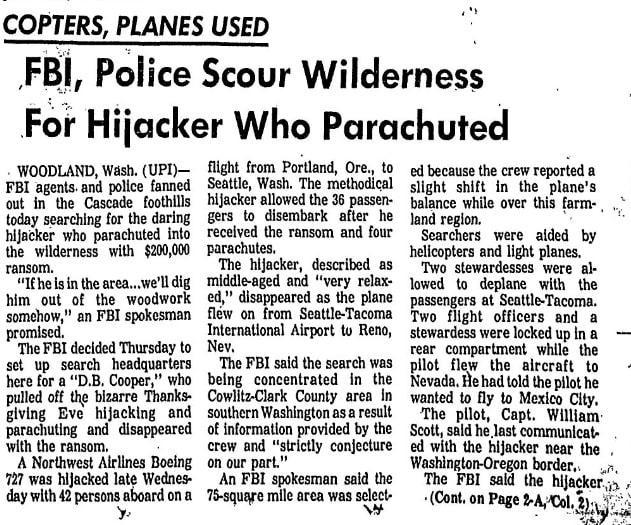

The crew explained that the 727 could not make it to Mexico City nonstop at 10,000 feet and 200 knots, and Cooper agreed to a necessary refueling stop at Reno-Tahoe International Airport (RNO).

But Cooper knew what he was doing. He specifically requested the configuration because he knew the aircraft well enough to understand what would happen to the aft airstair at higher speeds. He also knew the 727’s unique capability: those stairs could be lowered in flight.

Moments after a 1940 departure from SEA, Cooper told Tina to join the cockpit crew and close the curtain. She was the last person to see him.

Minutes later, the cockpit warning light indicated the aft airstair had deployed.

The Jump Into the Dark

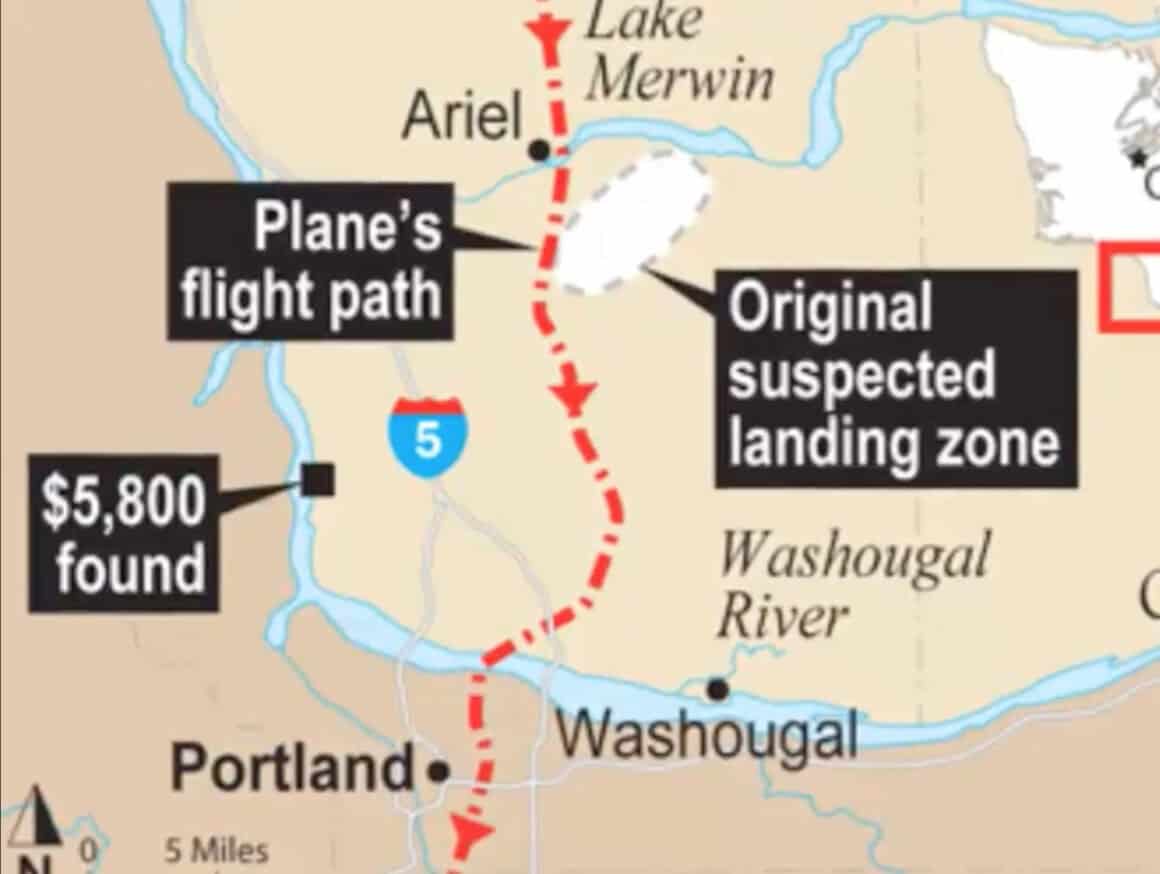

At approximately 2011 Pacific time, over rural Washington near Ariel and Lake Merwin, the cabin shuddered. A pressure bump registered. The crew felt tail oscillation.

And that was it.

Cooper, the parachute, and the canvas bank bag of cash were gone into a cold, rainy night at roughly 10,000 feet. Temperature: about 20 degrees Fahrenheit with wind chill. His outfit: business suit and loafers.

Two F-106 fighters dispatched from McChord AFB and a Lockheed T-33 trainer diverted from a mission saw nothing. Not too surprising, considering D.B. Cooper was wearing all black and it was a cold, dark, and stormy night in the Pacific Northwest.

Meanwhile, the aircraft continued on to Reno, the crew unsure if Cooper was still on board or not.

Hours later, at 2302 local time, Flight 305 landed safely at RNO (with the aft airstair still deployed). The FBI boarded the aircraft and found:

- Cooper’s black clip-on tie

- Eight cigarette butts

- Two parachutes

- A hair on the headrest

Cooper himself appeared to have evaporated.

A Skyjacking Era Hiding in Plain Sight

Today, the Cooper case stands alone as the most iconic unsolved hijacking in US history. But in late 1971, the skies were far less secure and far more chaotic than most modern travelers realize. Hijackings had become disturbingly common, and Cooper’s dramatic escape was only one chapter in a turbulent season for commercial aviation.

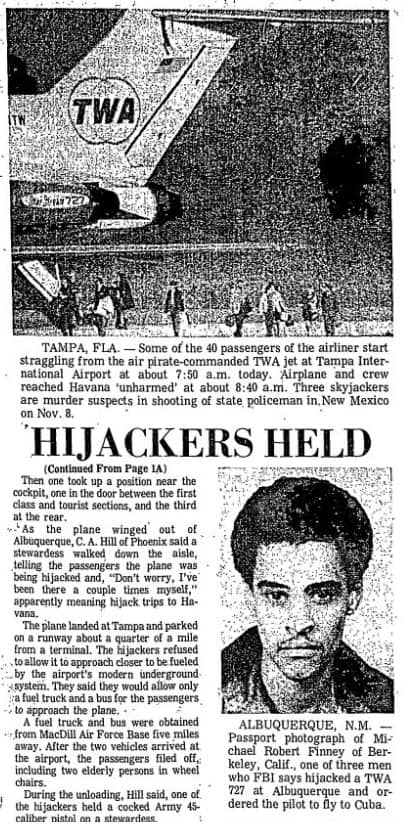

The impact on the news cycle was immediate. Just seventy-two hours after Cooper disappeared into the night, on 27 November, Trans World Airlines Flight 106 was hijacked at Albuquerque International Sunport by three armed fugitives wanted for the murder of New Mexico State Police Officer Robert Rosenbloom.

The men, linked to the Republic of New Afrika, hijacked a wrecker, stormed the parked Boeing 727, and forced the crew to fly them to Havana. All 45 passengers were released safely after a stop in Tampa, and Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro granted the hijackers political asylum.

Two US-registered airliners hijacked within three days. If that happened in 2025, the national security response would be immediate and overwhelming. In 1971, it was simply another reminder that commercial aviation was operating with virtually no modern security standards.

America’s Largest Manhunt

The search that followed was enormous. FBI agents, soldiers, and helicopters scoured a 28-square-mile region. They found nothing.

Not a parachute. Not a body. Nothing.

For nearly a decade, the Cooper mystery remained evidence-free. Then, in February 1980, eight-year-old Brian Ingram found $5,880 in decaying twenty-dollar bills on a sandbar called Tena Bar on the Columbia River near Vancouver, Washington. The serial numbers matched the ransom.

It remains the only significant piece of physical evidence directly tied to Cooper.

The Strange, Verified Details That Deepen the Mystery

• Cooper asked specifically for “negotiable American currency,” avoiding marked or sequential bills.

• He refused military parachutes and chose civilian sport chutes instead.

• He demonstrated knowledge of local geography. When someone referenced Tacoma’s distance, he corrected them.

• He insisted on configurations that kept the airstair stable.

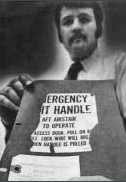

• A 1978 discovery of a 727 airstair placard near Castle Rock supported the estimated jump zone.

• The tie he left behind contained titanium particles, hinting he may have worked in aerospace or manufacturing.

• One parachute the FBI delivered was a dummy reserve sewn shut. Cooper spotted it instantly and left it behind.

• He offered to buy the flight crew meals in Seattle, using his own $20 bill.

The Case That Refuses to Close

The FBI officially suspended active investigation in 2016. But citizen sleuths continue to pore over the evidence. More than a dozen suspects have been proposed, from military veterans to former Boeing employees to con men with colorful histories.

Yet as of November 2025, none have been proven to be the man who stepped off the airstair of a 727 into aviation mythology.

Roughly $194,000 of the ransom remains missing. No parachute has been definitively tied to Cooper. And researchers still argue about whether he even survived the jump.

But the legend continues to fascinate because the story is almost too perfectly American: a calm, polite hijacker who sipped bourbon, knew his aircraft, paid for the crew’s dinners, and then disappeared into thin air on the night before Thanksgiving.

50+ Years Later, the Skyjacker Still Has the Last Word

Cooper left almost nothing behind except a clip-on tie, a pile of cigarette butts, and a puzzle that refuses to solve itself.

He jumped into a stormy night with $200,000 and a plan only he understood.

And to this day, Northwest Orient Flight 305 remains the last US commercial hijacking where the perpetrator was never found.

In other words: D.B. Cooper got away with it. And the Boeing 727 will forever carry one of aviation’s greatest mysteries in its wake.