Forty years after USAir Flight 499 overran a snowy runway in Erie, Pennsylvania, we examine how tailwind, speed, and snow combined to narrow the margins.

On the morning of 21 February 1986, USAir Flight 499 was approaching Erie International Airport (ERI) in Pennsylvania’s northwestern corner in instrument conditions that left little room for error. Snow was falling. The ceiling hovered at 200 feet. Visibility was 0.5 miles. Braking action had been reported fair to poor.

Within seconds of touchdown, the McDonnell Douglas DC-9-31 would slide off the end of runway 24, overrun a runway end light, break through a fence, and come to rest on a busy road 180 feet beyond the pavement, narrowly missing several vehicles on their Friday morning commute.

There were 23 people on board. One passenger sustained a minor head injury. There were no fatalities. But the accident became a clear case study in winter performance margins and operational decision making.

The Airplane and the Mission

The aircraft was DC-9-31 (reg. N961VJ), MSN 47506, delivered to Allegheny Airlines (USAir’s predecessor) in 1970 and powered by Pratt & Whitney JT8D-7B engines. By February 1986, it had accumulated more than 42,000 airframe hours.

Flight 499 was operating that morning on a routine flight from Toronto Pearson International Airport (YYZ) to what was then Greater Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT), with an intermediate stop in Erie. The captain had approximately 8,900 total flight hours, including 5,900 in the DC-9. The first officer (FO) had logged 4,880 hours total, 2,420 in type. Both were current and properly qualified.

The accident occurred at approximately 0858 local time during landing.

A Runway Slowly Deteriorating

Weather that morning was marginal from the outset. A special observation issued at 0650 reported a 300-foot overcast ceiling, 1.5 miles visibility in light snow and fog, temperature and dewpoint both at freezing, and wind 030º at 10 knots.

More significant than the ceiling was the runway condition. Runway 06/24 had been plowed, but only one snowplow was operational that morning. The operator acknowledged it typically left roughly one-quarter inch of snow behind. At 0715, braking action was checked with a decelerometer, which indicated fair to poor conditions.

The crew, who dutied in in Toronto around 0700, discussed the weather conditions. According to the NTSB report, the captain acknowledged that the weather in Erie was “not too good.” They determined that the fuel load was sufficient to hold if necessary and proceeded with the short 23-minute flight across Lake Erie as planned. Flight 499 pushed back from the gate at YYZ at 0756, 28 minutes behind schedule.

A Beechcraft King Air that landed around 0745 reported braking action as poor and estimated one to two inches of wet snow on the runway, with no bare spots visible. When that aircraft departed around 0815, the pilot still observed no exposed pavement and estimated roughly one-half inch of snow even on plowed sections.

Plowing was halted at 0820 in anticipation of Flight 499’s arrival. No sand or chemical treatment was applied. Light to moderate snow continued falling and intensified shortly before landing. No further plowing occurred for nearly 40 minutes.

By the time the DC-9 arrived on final, the runway was entirely snow-covered.

Runway 06 Out of Reach

The crew initially planned an ILS approach to runway 06. However, runway visual range (RVR) was reported at 2,800 feet, well below the required 4,000-foot minimum.

The captain elected to hold at 10,000 feet. Dispatch advised that if runway 06 minimums could not be met and landing on runway 24 with a tailwind was not authorized, the flight should continue to Pittsburgh.

Runway 24 required one-half mile visibility and was not equipped with RVR sensors. Reported visibility matched that minimum. At the suggestion of USAir’s Erie Ops, the crew requested an ILS approach to runway 24.

Initially, they believed winds were 330 at 9, effectively a crosswind near their allowable limit under reduced visibility conditions. But updated wind reports told a different story.

ERI Tower advised winds 010 at 10 knots. Moments later, winds increased to 15 knots and became variable between 010 and 020. On runway 24, those winds produced a 10 to 11 knot quartering tailwind component.

USAir’s DC-9 Pilots’ Handbook and Jeppesen advisory pages were explicit: tailwind components were not authorized for turbojet aircraft on runway 24 when the runway was wet or slippery. ERI’s runway 24, at just 6,500 feet, was one of five in the system with that restriction.

The crew received multiple wind reports indicating a tailwind component.

On short final, the FO attempted to reference the crosswind and tailwind component chart. The captain instructed him to put it away and focus on altitude callouts.

The airplane continued inbound.

Fast, Long, and Committed

Flight data recorder (FDR) data showed the DC-9 maintained 130 to 135 knots on final approach, approximately 13 to 18 knots above Vref, which was 117 knots for that landing weight.

The aircraft descended to the 200-foot decision height and remained there for approximately eight seconds before continuing the descent.

At approach speed, eight seconds is significant. The aircraft would have traveled well over 1,500 feet horizontally while holding altitude. In snow-obscured conditions with reduced runway definition, that forward movement shifts the eventual touchdown point.

The FO later stated that he saw the ground approximately 100 feet above decision height. At roughly 50 feet above minimums, he could see the approach lights and runway lighting but could not clearly define the runway surface itself because it was completely snow-covered.

Visual cues were present, but degraded.

Once descent resumed, touchdown occurred long.

FDR analysis placed main gear contact approximately 1,745 feet beyond the displaced threshold. Eyewitness measurements suggested as much as 2,130 feet beyond. In either case, roughly 4,000 to 4,250 feet of the 6,500-foot runway remained.

Both pilots described the touchdown as firm. Spoilers were armed but did not auto-deploy. On a slick, snow-covered surface, insufficient wheel spin-up likely prevented activation.

There was a seven-second delay before the nose gear contacted the runway. During that interval, the aircraft traveled an additional 1,200 to 1,400 feet.

The captain manually deployed the spoilers, lowered the nose, selected reverse thrust, and applied braking. He later reported that reverse thrust slowed the aircraft, but braking was not effective.

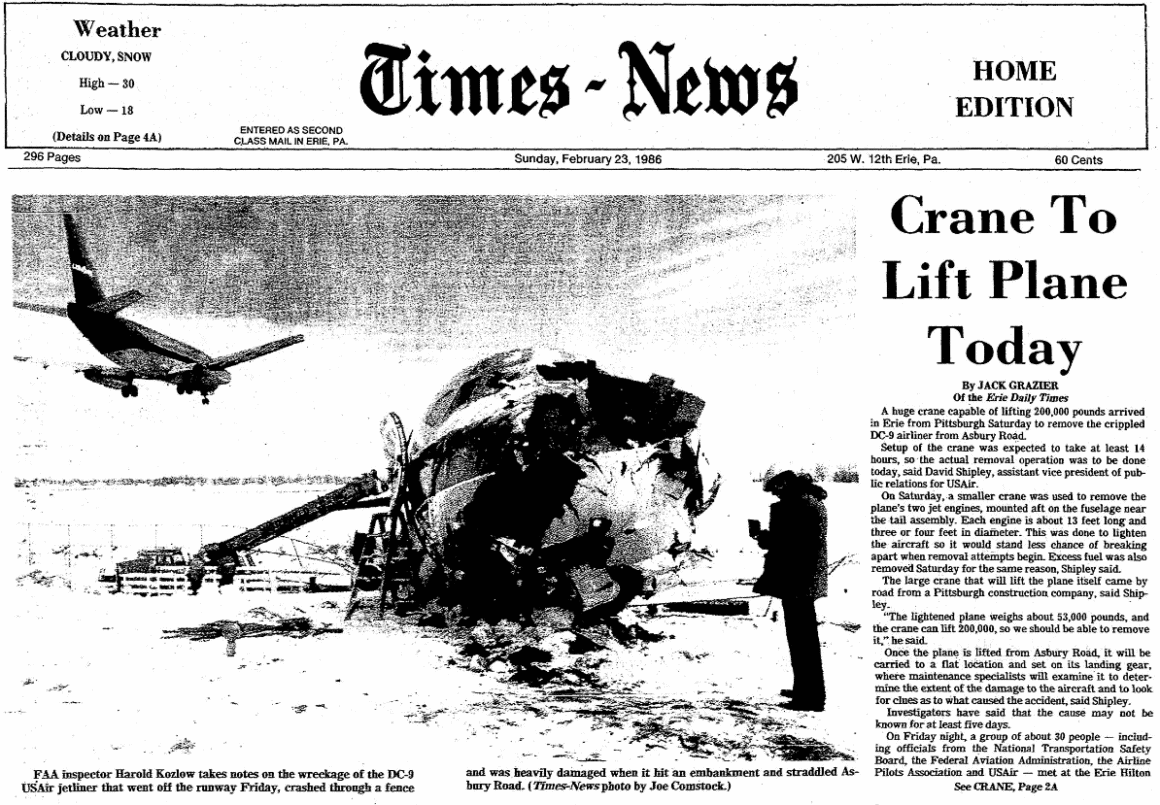

The DC-9 drifted left and exited the runway surface at approximately 44 knots. It ran over a runway end identifier light, struck a chain-link fence, descended a 20-foot embankment, and came to rest straddling a road 180 feet beyond the runway end.

Evacuation was textbook: Flight attendants deployed the forward slide, ushering passengers off the aircraft. The crew secured the cockpit, checked for leaks (none), and notified the tower. The DC-9 was substantially damaged and later written off.

The Arithmetic of Stopping

Douglas Aircraft and NTSB analysis determined that approximately 4,087 feet of stopping distance were required from the point of main gear touchdown under the existing configuration, tailwind, excess speed, and runway condition. That figure included the seven-second delay before nose lowering.

Had the nose been lowered immediately, allowing spoilers to deploy upon nose gear compression and reverse thrust to be applied without delay, stopping distance could have been reduced to roughly 2,750 feet.

Even so, company policy explicitly prohibited landing on runway 24 with any tailwind component when the runway was wet or slippery.

In the end, the NTSB concluded that the crash of Flight 499 was not the result of one mistake. It was a cascade.

The tailwind restriction was overlooked. The approach was flown fast. The aircraft floated at decision height. Touchdown came long. Deceleration was not optimal.

The DC-9 handbook had addressed nearly every one of those variables. It warned that the first 2,000 feet on a slush-covered runway are the most critical because hydroplaning reduces braking effectiveness. It emphasized monitoring spoilers on slippery surfaces, since automatic deployment depends on wheel spin-up or nose gear compression. It outlined strict limitations for wet snow operations.

The crew had the information. But weather, shifting winds, and short-final workload blurred the lines between procedure and execution.

The dispatcher, relying on the wind information relayed by the crew, deferred to their on-scene judgment, as company protocols require. Air traffic control provided all available weather updates. Nav aids checked out post-accident. No mechanical discrepancies were found.

What remained was performance math.

A Personal Footnote, Forty Years Later

I was seven years old when Flight 499 slid off the end of runway 24. It happened just three miles from my childhood home. As a kid already obsessed with aviation, I remember watching the coverage and following every detail of the cleanup and investigation. My dad drove me to the accident site multiple times, and we were there when the DC-9 was lifted from the roadway by crane.

Less than a month earlier, the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster had shaken the nation and dominated headlines across the world. That event brought national grief. Flight 499 barely registered in the national headlines of the day. Outside of Erie, few people likely remember it. No one was killed. Only one passenger was injured.

But locally, it was unforgettable. For a young boy already fixated on aviation, it became one of those early memories that quietly and permanently imprints itself.

Looking back four decades later, it is hard not to see how that snowy winter morning deepened my fascination with aviation. Not because of spectacle, but because of the discipline behind it. Performance charts. Tailwind limitations. Runway contamination. The unforgiving math of stopping distance.

Thankfully, Flight 499 did not end in tragedy.

But on a snowy morning in Erie, the lessons learned from USAir Flight 499 reinforce the hard truth that in aviation, margins are never abstract. And in winter conditions especially, every inch and every knot counts.