If an airline could wear a city like a jacket, New York Air did it. The little airline had attitude, but it never really gained enough altitude to survive the turbulent era of the late ’80s.

New York Air began operations in 1980 and was based at Hangar 5 at New York’s LaGuardia International Airport (LGA). New York Air was created as an offshoot of Texas Air, designed to compete with the few airlines based in the area by offering frequent and affordable flights in the region.

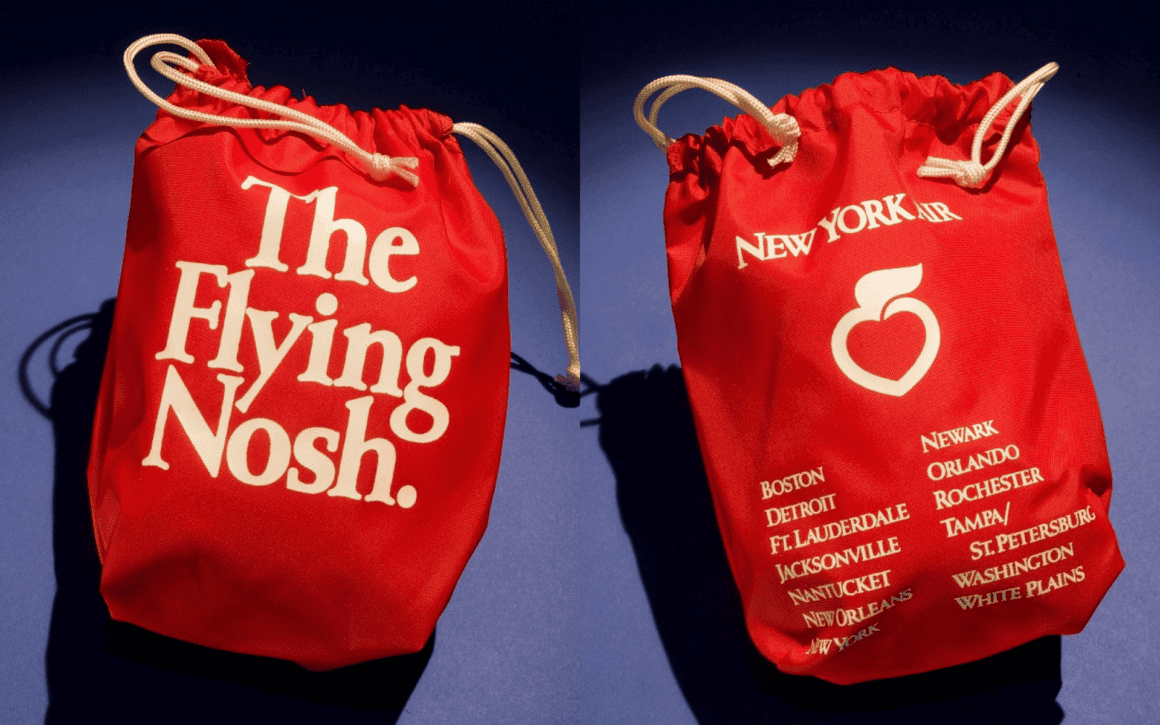

New York Air was a small airline with only a few destinations and a small fleet, but it had a loyal following. The carrier became famous for one oddly lovable onboard detail: bagged snacks called “The Flying Nosh.”

Then, just as quickly, it disappeared. On 1 February 1987, New York Air ceased operations as it was folded into Continental Airlines as part of Frank Lorenzo’s bigger Texas Air consolidation play.

And if you’re wondering whether it ever truly “made it” in New York, the answer is…well, complicated. New York Air had swagger. It had ideas. It had a brand. But it never quite got enough altitude to survive the late deregulation dogfight.

A Deregulation-Era Upstart with a Simple Plan: Be Cheaper, Friendlier, and Frequent

In September 1980, Frank Lorenzo’s Texas Air announced plans for a new low-fare airline in the Northeast. The timing mattered: airline deregulation had opened the door for new carriers to expand without the old government guardrails, and Texas Air was eager to take advantage.

New York Air’s first big target was obvious: Eastern Air Shuttle.

Eastern owned the rhythm of the Northeast Corridor, running frequent service between LGA, Boston Logan (BOS), and Washington National (DCA). New York Air planned to run a similar “show up and go” style schedule, but with lower fares, advance reservations, and something Eastern didn’t always emphasize at the time: complimentary drinks and snacks.

There were even early plans for a big operation at Westchester County Airport (HPN), though that never fully materialized.

Built in a Blink: 90 Days from Concept to Cockpit

New York Air moved at a pace that feels almost impossible now.

Its founding president, Neal F. Meehan, had management experience at Continental and Texas International (another Texas Air subsidiary). He assembled a team and, within about 90 days, New York Air had hired, trained, uniformed, and drilled crews and staff across the operation, including pilots, flight attendants, dispatchers, terminal and ramp teams, and reservations personnel.

In one memorable vignette from the airline’s origin story, management interviewed more than 1,000 job candidates in a single day at group interviews held at New York’s Town Hall Theater in November 1980.

The airline’s office and maintenance setup were completed quickly inside Hangar 5 at LGA, which had previously housed American Airlines operations in the 1930s. New York Air gained FAA certification as an adjunct to Texas International’s certificate.

The Inaugural Flight: Big Ambitions, (Really) Tiny Load Factor

New York Air officially began flying on 19 December 1980, launching with a LGA-to-DCA flight.

Only five seats were filled on that first trip. Yes, five.

At the time, the New York City market actually suffered from a lack of low fares. Therefore, New York Air’s formula of low fares and friendly service caught on quickly. They had low walk-up fares (important at the time because flights could only be booked by a travel agent or over the phone).

The airline improved its load factor quickly, but not quickly enough to avoid losses. By April 1981, it averaged about a 62% load factor, flirting with a break-even point of around 65%, but still reported a loss of $1.5 million. Executives called it a “moderate success,” then raised fares on LGA flights as reality set in.

Early Growth, then the One-Two Punch: Competition and the PATCO Strike

New York Air expanded fast anyway.

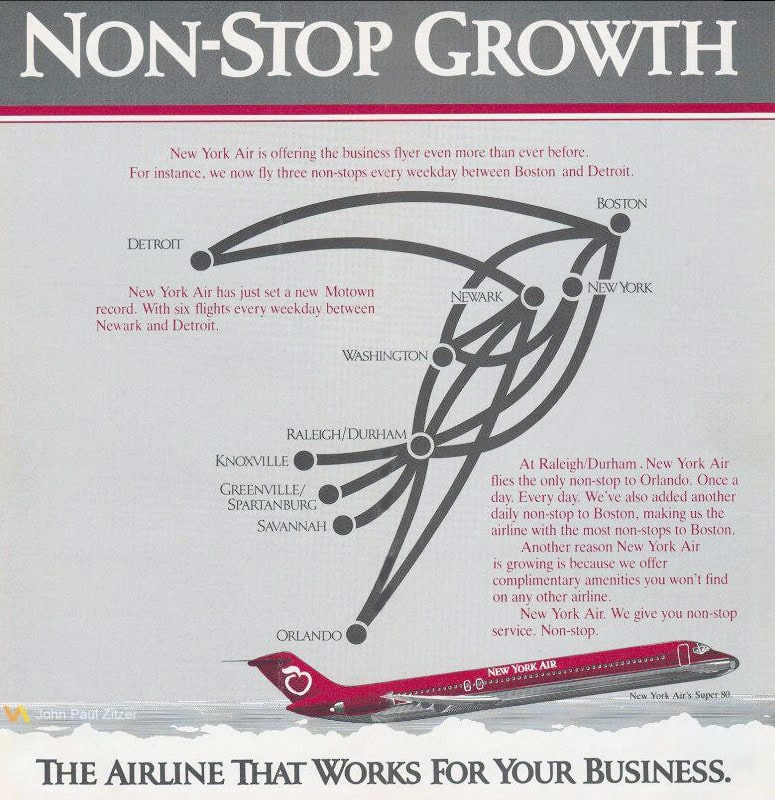

It built a hub-like operation at LGA, added routes to destinations like Cleveland Hopkins (CLE) in April 1981, and established smaller focus operations at BOS and DCA. However, several planned destinations were cut, including Dayton (DAY), Pittsburgh (PIT), and a handful of Upstate New York routes. It also tried LGA-Detroit Metro (DTW) briefly before shifting that flight to Newark (EWR), where it started a secondary operation.

By late 1981, the carrier had ramped up service to destinations such as Cincinnati (CVG) and Louisville (SDF), and had expanded its fleet to thirteen DC-9-30 series aircraft.

Then came a huge external problem: the 1981 PATCO strike.

The strike resulted in delays that discouraged passengers from flying, and the FAA reduced the number of slots at congested Northeastern airports. Big carriers had a workaround. Eastern, for example, could swap in larger aircraft, such as the Airbus A300, keeping passenger volume steadier even with fewer flight slots.

New York Air couldn’t. With a small fleet and limited aircraft size flexibility, the slot reductions and a suddenly more aggressive competitive environment hit hard. The airline ended its Boston shuttle presence in its early form after less than a year.

It tried to maintain a foothold at BOS with routes to Baltimore (BWI) and Orlando (MCO), but BOS proved unprofitable and was shut down by the end of 1982.

“Runaway Shop”: Union Disputes and a Very Public Fight

New York Air was set up as a non-union airline, which immediately angered organized labor, particularly ALPA and unionized staff at Texas International. Critics branded it a “runaway shop,” arguing Texas Air was creating a parallel non-union operation to sidestep union contracts.

Within a week of New York Air’s launch, Texas International employees were picketing at LGA. Meehan denied the accusations, insisting New York Air was separate and would negotiate if employees chose to unionize.

ALPA didn’t let up.

By mid-1981, ALPA was running what it described as a political-style campaign against the carrier. The messaging was sharp and memorable, including materials calling New York Air “Texas Air’s Bad Apple,” complete with an edited logo featuring a rotten apple. The campaign highlighted operational issues like poor on-time performance and overbooking, and “Please Don’t Fly New York Air” badges appeared.

Even New York Air’s headline-grabbing promotional fares backfired in a way. The airline’s famous “29 cent fare” moment, a limited in-person promotion tied to the inauguration of New York to Boston service, created massive crowds. Local media covered the chaos, and ALPA picketers used the attention to amplify their anti-New York Air message to people waiting in line.

The Pivot: From Low-Cost Upstart to Premium-Leaning Business Carrier

By 1982, the numbers were ugly. The airline reportedly lost $11 million in 1981 and then incurred another $8.2 million loss in the first quarter of 1982.

Meehan resigned as president in July 1982. Michael E. Levine took over leadership, and the airline changed its posture.

New York Air began repositioning as a more full-service product aimed at business travelers, offering a more premium experience while still typically undercutting competitors on fares. Levine trimmed the network, focusing on markets with business demand, and adjusted the shuttle schedule so that LGA departures ran on the hour, rather than every half-hour.

And it leaned hard into onboard touches: complimentary bagels on morning flights, wine and newspapers, plus other “this feels a little nicer than you expected” details.

This is also where New York Air’s snack identity really stuck. The airline was well known for its onboard snack bags, “The Flying Nosh,” which became a mini brand of its own.

Hubs and Experiments: Raleigh-Durham, the Apple Club, and the Dulles Bet

New York Air didn’t just fight for scraps in New York. It tried to build connecting flows too.

In 1983, it launched a small hub operation at Raleigh-Durham (RDU), with service to cities such as Greenville/Spartanburg (GSP) in South Carolina, McGhee Tyson Airport (TYS) in Knoxville, Tennessee, Savannah (SAV) in Georgia, and later MCO, along with feeder flying on commuter partners like Air Virginia and Sunbird Airlines.

At RDU, it also offered a private boarding lounge called the Apple Club, reinforcing that “premium, but still a deal” identity.

The RDU hub ultimately didn’t last, with routes gradually disappearing by the mid-1980s.

The bigger swing came in Washington Dulles (IAD).

In July 1985, New York Air announced it would open a hub at IAD, building a new concourse at a reported cost of $3.6 million, featuring an Apple Club restaurant. By the end of 1985, it had established a sizable schedule there and was increasingly making IAD its operational focus.

Meanwhile, New York Air kept LGA and BOS in the mix and, by 1986, began leaning more into regional feed. New York Air Connection was the branded commuter service that helped funnel passengers from smaller markets into the mainline network. Operated by Colgan Air, it used aircraft like the Shorts 330, Beechcraft 1900, and Beech 99s on select routes. The “Connection” branding also popped up on seasonal flying to leisure spots like Martha’s Vineyard (MVY) and Nantucket (ACK), helping New York Air reach beyond its core shuttle-and-business footprint.

New York Air also relied on other feeder partnerships, including Air Virginia and Sunbird Airlines, to support connections through RDU’s short-lived mini-hub.

The Fleet and the Look: DC-9 Muscle, MD-80 Shine, and a Dash of 737

New York Air’s fleet story matched its era. It leaned heavily on proven workhorses, then scaled up as it stabilized.

At its peak, the airline operated 40 aircraft, most in a bold red scheme with the stylized apple tail logo:

- 20 McDonnell Douglas DC-9-30

- 12 McDonnell Douglas MD-82

- 8 Boeing 737-300

The 737-300s arrived after Texas Air ordered 24 of them in 1984, with some delivered to New York Air starting in 1985. It was the first time New York Air operated Boeing jets, and a noticeable shift from its McDonnell Douglas-heavy identity.

And yes, the branding worked. The aircraft were painted bright red and had a clever apple painted on the side as a shout-out to the “Big Apple.” You couldn’t help but think of the gaudy Big Apple at Shea Stadium when you saw that tail.

The End Game: Texas Air Consolidation and the Continental Merge

By 1986, Texas Air was coordinating its subsidiaries more tightly. New York Air began cooperating with Continental and other Texas Air holdings, including code-sharing and a marketed partnership sometimes branded as a team effort.

Then came the inevitable consolidation move.

In January 1987, Texas Air announced it would merge New York Air, People Express, and Frontier into Continental. New York Air ceased operations on 1 February 1987, and its aircraft were repainted into transitional schemes that read “Continental’s New York Air.” Over time, their cleverly painted aircraft became adorned with “meatballs” on the tail.

Some elements of the shuttle concept lived on under Continental for a time, particularly around EWR, but the New York Air name and identity quickly faded into airline history.

The Legacy: A Small Airline with Big City Personality

At its height, New York Air employed over 2,000 people. Although it only existed for about six years, it left behind a very specific kind of nostalgia.

It was born out of deregulation ambition, took an unapologetic swing at one of the most iconic short-haul markets in the country, and proved that branding and service touches could matter even when you were the underdog.

It had “The Flying Nosh.” It had the apple tail. It had the nerve to challenge Eastern in its own backyard.

And for a brief moment, it made the idea of a scrappy Big Apple airline feel totally believable.