This B-24D Liberator’s Crew Never Stood a Chance Against the Endless Sahara.

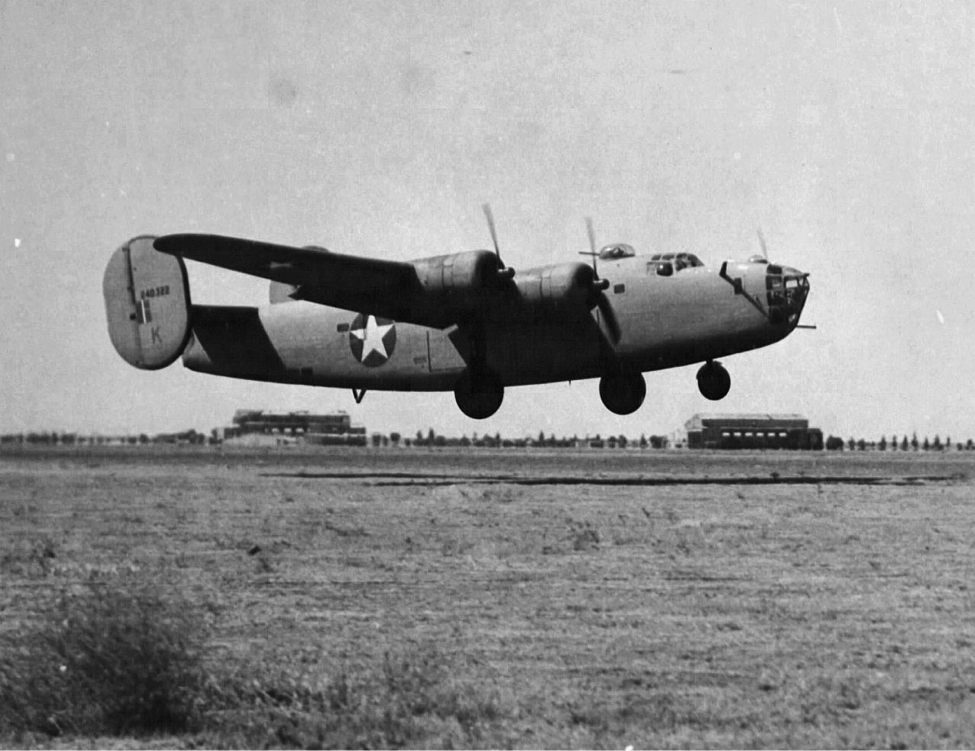

On 4 April 1943, the Consolidated B-24D Liberator “Lady Be Good” and her crew of nine men took off on their first combat mission from Soluch airstrip in Benina near Benghazi in Libya to bomb the harbor of the Italian city of Naples…but flew into history instead. The aircraft disappeared without a trace. Written off as one of the thousands of American heavy bombers lost during the war, the Lady would most likely remain undiscovered and her disappearance would almost certainly remain unsolved. At least until 15 years later.

The Lady’s Crew

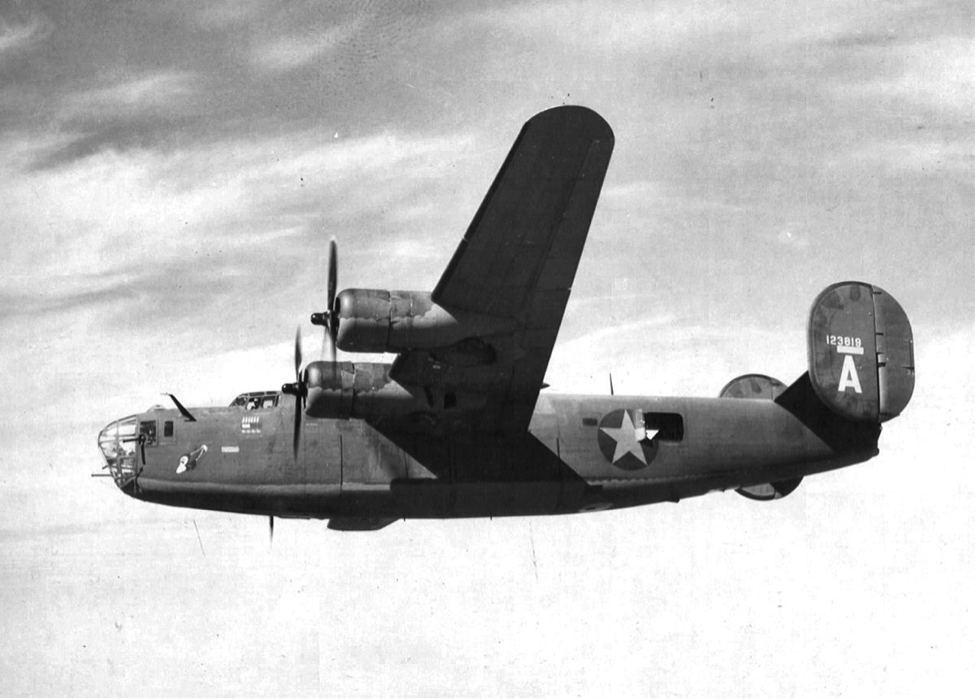

The Lady , also known as Consolidated B-24D Liberator serial number 41-24301 (MSN 1096), was assigned to the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) 514th Bomb Squadron of the 376th Bomb Group (Heavy). Part of a 25 bomber mission that day, the Lady was supposed to bomb Naples harbor as a part of the second wave of a two-wave attack. The Lady was crewed on that fateful day by pilot First Lieutenant William J. Hatton from Whitestone in New York, co-pilot Second Lieutenant Robert F. Toner from North Attleborough in Massachusetts, navigator Second Lieutenant D.P. Hays from Lee’s Summit in Missouri, bombardier Second Lieutenant John S. Woravka from Cleveland in Ohio, flight engineer Technical Sergeant Harold J. Ripslinger from Saginaw in Michigan, radio operator Technical Sergeant Robert E. LaMotte from lake Linden in Michigan, gunner and assistant flight engineer Staff Sergeant Guy E. Shelley from New Cumberland in Pennsylvania, gunner and assistant radio operator Staff Sergeant Vernon L. Moore from New Boston in Ohio, and gunner Staff Sergeant Samuel E. Adams from Eureka in Illinois.

Fateful Decision to Continue the Mission

The Lady’s departure from Soluch Airstrip near Benina, Libya was routine but the Liberator ran into a Sahara desert sandstorm with high winds and obscured visibility which prevented the aircraft from joining up with the rest of the formation. Most of the other aircraft returned to Soluch upon encountering the sandstorm but the Lady continued the mission. Upon reaching Naples at approximately 1950 local time the primary target was obscured so only two of the B-24Ds dropped their bombs on the primary. Two others, including the Lady, jettisoned their bombs in the Mediterranean. The Lady flew back to the Soluch airstrip at Benina alone.

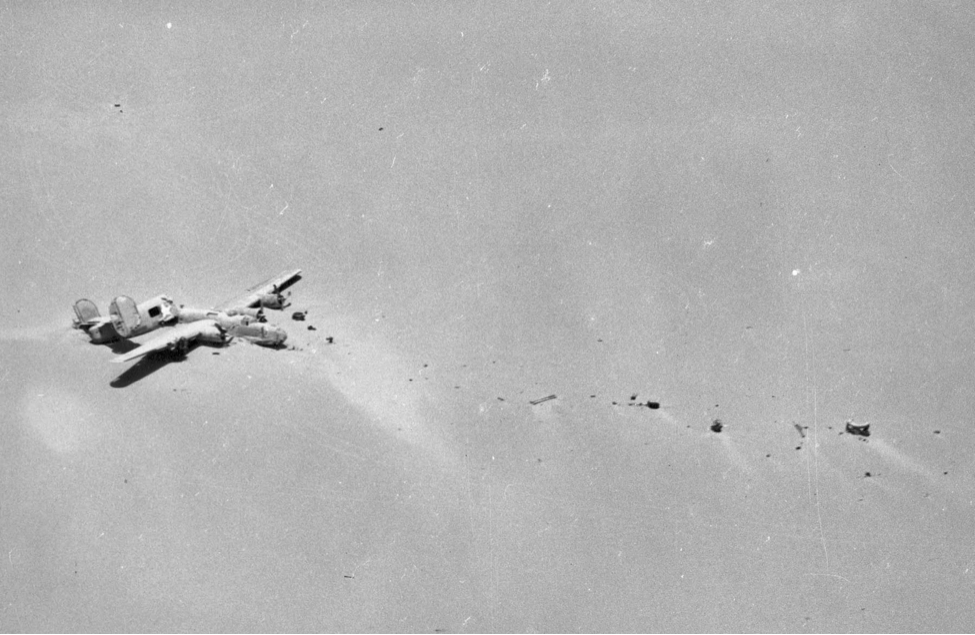

Flight to Oblivion

At 0012 local time command pilot Hatton radioed Soluch to indicate that his automatic direction finder (ADF) was not working properly. He asked for steer back to the base that the Lady never received. By all accounts the Lady overflew Soluch Airstrip but failed to observe flares fired from the ground to attract the crew’s attention. The Liberator continued its flight…deeper into the Sahara desert until 0200 local time when the crew abandoned the Lady, parachuting to the desert ground. The B-24D flew another 16 miles before she crashed landed in the Calanshio Sand Sea. A search and rescue mission was immediately mounted from Soluch but all efforts to locate the Lady and her crew failed to find any trace of the aircraft or the men. At that point the fate of the Lady Be Good became another unsolved mystery of the Sahara.

Lost and Then Found

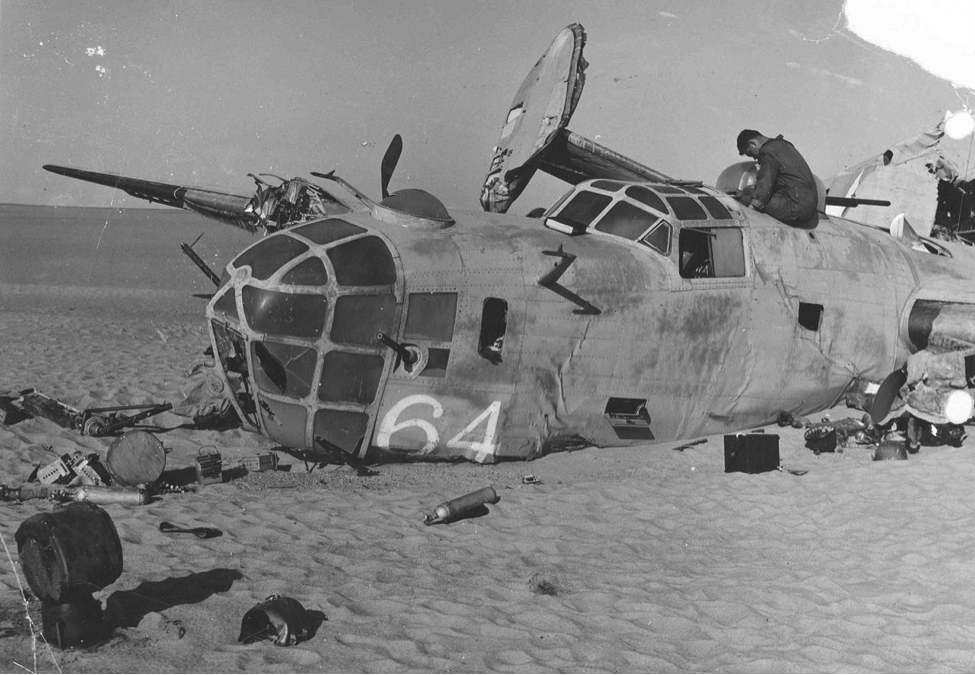

The first to sight wreckage of a B-24D that could be the Lady was a British Petroleum (BP) oil exploration team roaming the Libyan deserts on 9 November 1958. When the Brits contacted the nearest American base (Wheelus Air Force Base near Tripoli in Libya), they were told that there were no records of an American plane that had been lost in the area. As a result, no immediate attempt to examine the wreckage was made but the BP team marked the location of the wreckage on their maps. Sighted from the air again on 16 May 1958 and 15 June 1958, a recovery team finally arrived at the wreck on 26 May 1959.

Like She Wanted to Land on Her Own

From the condition of the wreck it was deduced that after the crew abandoned the aircraft the Lady continued flying southward. The wreckage was in large part intact and there was evidence that suggested one engine was still operating at the time of impact. This in turn suggested that the Liberator lost altitude only gradually in a shallow descent, eventually belly landing on the desert sands. Although the plane was broken into two large pieces the desert had not ravaged the Lady quite as much as the recovery team expected.

A couple of corrections: the Lady be good DID join the formation and was the lead bomber when the last four turned back (aborted). The recovery did arrive on May 26, 1959, but the oil team had already visited her on February 27, 1959 and they notified the air force of the finding. It was COFFEE not tea that was found in the thermos. It was the oil team that found seven of the eight bodies. The Air Force only found Ripslinger’s body. It was only two of the three bodies that separated were found. Moore’s body has never been found. The arm rest that was found was only a copy of the arm rest from the Lady.