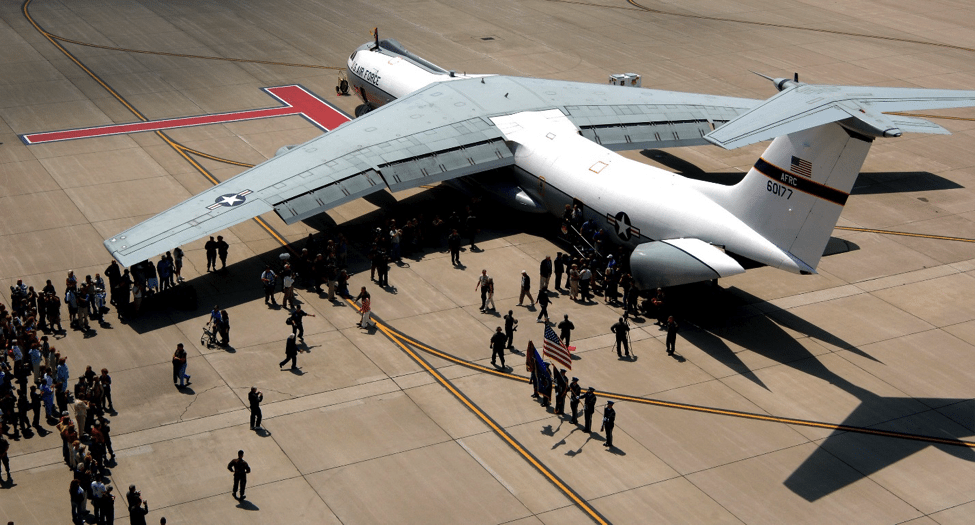

Operation Homecoming returned POWs from North Vietnam. Tail number 66-0177 held a unique place in the hearts of wartime heroes, aircrew, entertainers and avgeeks.

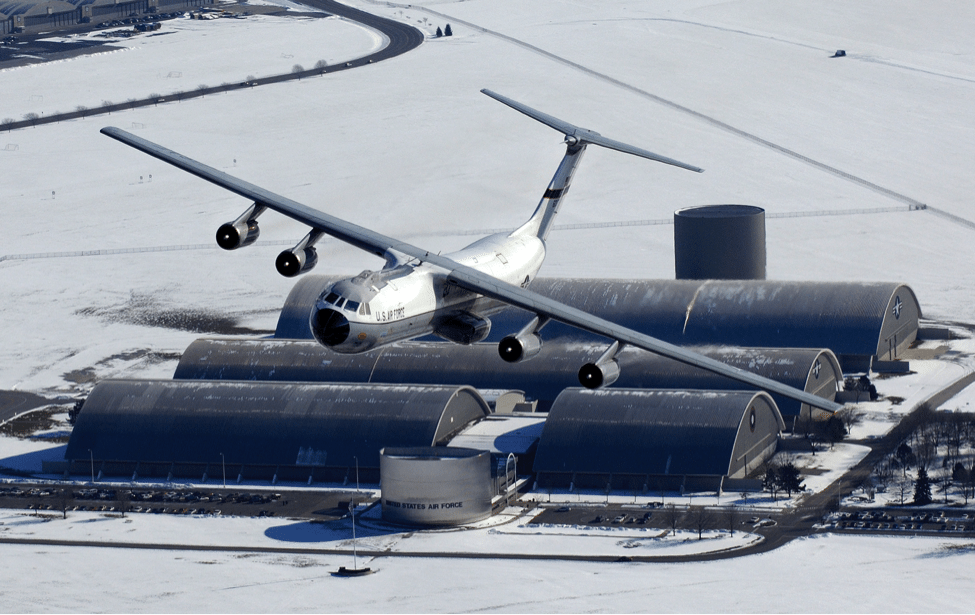

On March 12th 1998, a United States Air Force Lockheed C-141B Starlifter transport (Air Force serial number 66-0177, AKA the “Hanoi Taxi”) departed Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. A C-141 flight out of Wright-Pat was a common enough occurrence, but this one was special. Onboard were more than 50 former American prisoners of war. The Starlifter’s destination was Randolph Air Force Base in Texas, the site of the 25th Annual Reunion of the Freedom Flyers.

That particular C-141 had flown some of these passengers before. On February 12th 1973 the very same aircraft flew the first mission to repatriate the first 40 American prisoners of war released by North Vietnam from Gia Lam airport in Hanoi.

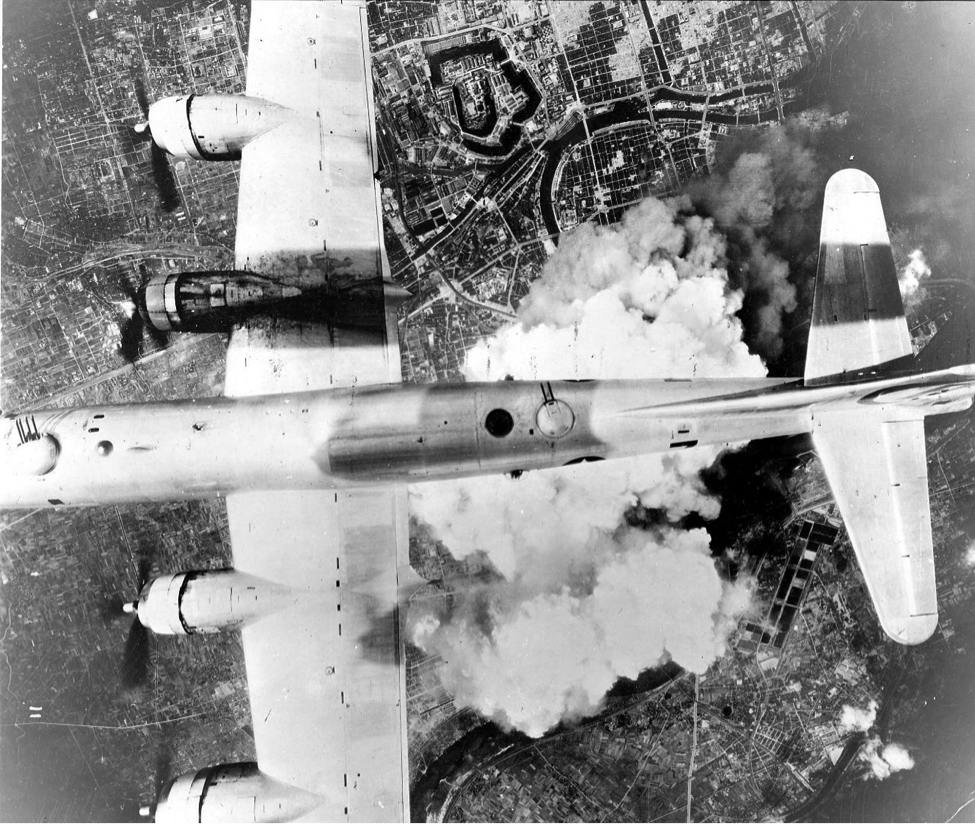

From February 12th through April 4th 1973, C-141s flew 54 Operation Homecoming missions out of Hanoi returning 591 prisoners of war to their country and families. Air Force Technical Sergeant James R. Cook, who suffered severe wounds when he bailed out of his stricken aircraft over North Vietnam in December of 1972, saluted the American Flag from his stretcher as he was carried aboard the aircraft.

Also on the first flight was Navy Commander Everett Alvarez Jr. The first American pilot to be shot down in North Vietnam, Alvarez was the longest-held POW, having spent more than eight years in captivity. Celebration broke out aboard the Hanoi Taxi when it lifted off on its way out of North Vietnam, as the former POWs experienced their first taste of freedom.

Speaking to the crowd that lined the tarmac at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines to welcome the aircraft on its first stop, returning POW Navy Captain Jeremiah Denton was cheered as he thanked all who had worked for their release and proclaimed, “God bless America.” Denton continued his naval career, eventually rising to the rank of Rear Admiral. He was later elected to represent Alabama in the United States Senate.

United States Air Force Captain Larry Chesley recalled that “everything seemed like heaven” after having spent seven years as a prisoner of the North Vietnamese. “When the doors of that C-141 closed, there were tears in the eyes of every man aboard,” he said.

The senior officer at the Hanoi Hilton, Air Force Colonel Robinson Risner, choked back his emotions as he arrived at Clark on the second C-141 flight from Hanoi. “Thank you all for bringing us home to freedom again,” he told the gathered crowd.

The last Vietnam POW to serve in the Air Force, Major General Edward Mechenbier, recalled the emotion of his own Operation Homecoming flight out of North Vietnam on February 18th 1973. “When we got airborne and the frailty of being a POW turned into the reality of freedom, we yelled, cried and cheered,” the General said.

The first group of 20 former POWs to make it all the way home arrived at Travis Air Force Base in California on February 14th 1973. News clips of their arrival and the tearful scenes planeside revealed the emotions of the freed POWs.

Navy Captain James Stockdale remarked, “The men who follow me down that ramp know what loyalty means because they have been living with loyalty, living on loyalty, the past several years — loyalty to each other, loyalty to the military, loyalty to our commander-in-chief.” Though permanently injured before and during his ordeal as a POW, Stockdale continued his naval career rising to the rank of Vice Admiral.

Starlifter 66-0177, later named Hanoi Taxi, continued to serve the country after Operation Homecoming. The aircraft was reworked with the standard C-141A upgrades and modifications, such as a lengthened fuselage and the addition of aerial refueling capability, resulting in designation changes to C-141B and later to C-141C. 177 even flew entertainer Bob Hope to Vietnam for his USO tours.

The Hanoi Taxi had been maintained by the Air Force as a flying tribute to the POWs and MIAs of the Vietnam War. When the Boeing C-17 Globemaster III replaced the venerable machine, the Air Force wanted the aircraft to be preserved. After her final missions of mercy evacuating victims of Hurricane Katrina, C-141C Air Force serial number 66-0177, the Hanoi Taxi, and the last operational C-141C in Air Force service, was officially retired to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Pat on May 6th 2006.

[youtube id=”6lpbfvErfNs” width=”800″ height=”454″ position=”left”]