It’s a question that almost every avgeek has asked before: Why didn’t McDonnell Douglas make a serious attempt to sell a tanker version of the MD-11 tanker to the Air Force? Back in the early 1990s, the MD-11 program was struggling to meet promised performance targets. American became so frustrated with their aircraft that they eventually cancelled their order. The theory is that McDonnell Douglas could have revitalized the program while the Air Force could have replaced aging KC-135s (sound familiar?) and compliment existing KC-10s.

Our friends at Seattle Model Aircraft put together a post explaining why a KC-11 (officially designated as a KC-10B never materialized).

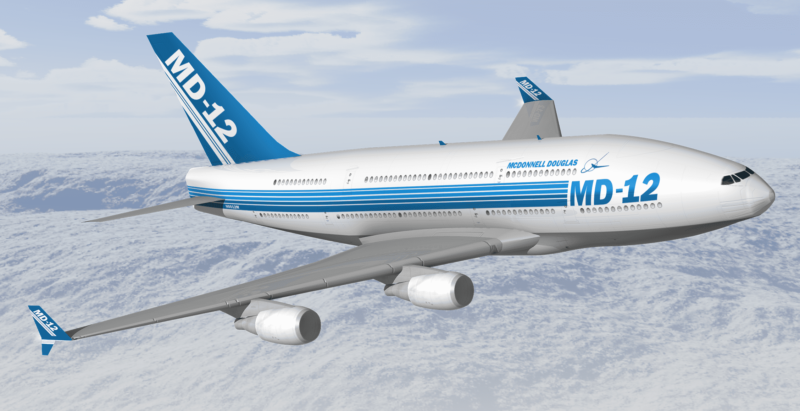

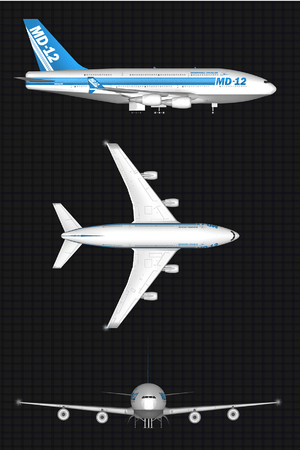

After McDonnell Douglas did the KDC-10 conversion for the Royal Netherlands Air Force in 1992, they proposed a tanker/transport version of the MD-11 which had the in-house designation KMD-11. McDD offered either conversion of second hand aircraft or new build aircraft- compared to the KC-10A Extender (which was itself based on the DC-10 Series 30 as were the Dutch KDC-10s), the proposed KMD-11 offered 35,000 lbs more cargo capacity and 8,400 lbs more transferable fuel.

There had been some in-house work since the early days of the MD-11 program on using the MD-11 as a tanker going back as far as 1987. As a frame of reference, the MD-11 program was launched in 1986. The designation KC-10B was supposed to have been assigned should such a tanker variant enter service with the USAF.

Interestingly I came across this tidbit on an aviation forum from a KC-10A Extender pilot on why an MD-11 tanker was pointless. It was posted back in 2004, but a lot of it still has bearing today:

“The efficiency comparison between the MD-11 and KC-10 is effectively no factor. The KC-10 only operates at MTOW a relatively small amount of time. Our MTOW of 590,000 lbs is already 10,000lbs heavier than the DC-10-30F and MD-10-30F, and is only 40,000 lbs less than the MD-11F (with full aileron droop mod, considering some of the past problems with this, the USAF would probably go with the 618K MTOW, for a 28,000 lb difference). Once you ad the Boom, drogue, and UARRSI the weight and CG shift will bring the MD-11 ACL down considerably. We can hold over 350,000 lbs of fuel by volume, but only around 335,000 lbs by weight. I can count the number of 590K takeoffs I have done on one hand. I have never done, and don’t even know anyone that has carried more than 120k or so in cargo weight, (Deuce50 can confirm this) and that much cargo seriously limits fuel available for cruise. Our money maker is the ability to move fighters and some support cargo at the same time, and for that we need fuel. Our body fuel tanks are limited by “zone load” restrictions for fuel weight. That means to put more fuel weight in the body, Boeing would be doing some considerable structure mod in the MD-11. The smaller MD-11 horizontal stab will also affect the CG range, something that requires additional “ballast fuel” in the KC-10 already, not to mention alleviating the usefulness of the MD-11 horizontal stab tanks with the boom installation. Another factor with additional fuel weight is single engine dump capability. Neither acft have the capability to jettison cargo, so your stuck with it regardless of your configuration, however fuel dump in a single engine situation could be the difference between walking or swimming to the crew bus, and it leaves at the same rate on both acft. This is partially negated by the increase in MD-11 thrust, but still a volume issue The USAF also uses ALL the runway surface to compute V1 speed, IE we aren’t required to be 35 feet above the departure end unless there are obstacle clearance issues. This means at USAF terps’ed airfields we can leave much heavier than at an FAA field, which gives us comparable performance out of shorter USAF fields, but affecting Vmcg and a few other takeoff numbers. This would be a benefit for the MD-11, but only if an increased fuel volume was available, as it normally limits our MTOW quite a bit. Another factor is operating environment. The MD-11’s CF-6-80 has about 8,000 lbs more thrust per engine, but at 45c this doesn’t help much, and the weight will still hover around the current KC-10. In the end, the KC-11’s performance would only slightly exceed the current KC-10 capabilities, which would be outweighed by the problem of dissimilar engines and equipment cost.”

“If you want to help the KC-10, advocate the purchase of a few DC-10-30’s to use for our endless touch and goes to save wear and tear on the current fleet.”

“I am all for more KC10-11’s, but only if it will add to what we have, not replace the ‘135. The analogy has already been given that the world’s biggest gas station does no good if you only have one pump. We need more booms, not bigger ones.”

The proposed KMD-11 also had underwing HDU (hose drum units) for refueling probe-equipped aircraft, something this FlightSim depiction lacks.