When the Korean War began in 1950, the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy focused on air interdiction missions, attacking lines of communication and supplies. These included targets like bridges, trains, trucks, storage facilities, and troops. In 1952, however, the Air Force and Navy shifted their focus to more strategic targets like dams and power generation stations. One of their most valuable targets was the Suiho Dam.

Strategic Targets Were Not a Focus in the Early Days of the War

During the early days of the Korean War, U.N. forces mostly avoided attacking Korean dams and power stations. Partly, this was because planners decided to focus attacks on interdiction targets. However, that wasn’t the only reason.

By 1949, most of the world’s nations had signed the Geneva Conventions. This agreement was focused, in part, on protecting victims of armed conflicts. Destruction of dams and power stations would clearly cause harm to civilians. U.N. forces also initially held off on attacking the dam out of concern that it would bring China into the war.

As the war continued, the U.N. and Communist sides began negotiating for a possible truce. One of the key points was to reach an agreement on the repatriation of prisoners of war. In early 1952, U.N. strategists, mostly American admirals and generals, became frustrated when they felt the Communist side was stalling and uninterested in a peace agreement. Therefore, they shifted air attacks to more strategic targets, hoping to force the Communists to consider peace seriously. The primary strategic targets would be hydroelectric dams.

Suiho Complex a Key Strategic Target for Bombing Missions

Planners chose the Suiho Complex as one of the prime targets for strategic bombing. The Japanese built Suiho in 1940. It had six of the world’s largest turbine generators. The reservoir behind the dam held 20 billion cubic meters of water, similar to the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State.

Each massive turbine generator produced 100,000 kW of power. Besides producing most of North Korea’s electricity, it also supplied power to major Chinese and Russian ports and military bases up to 100 miles away.

As negotiations continued to stall, the Americans planned to attack Suiho in June 1952. It would not be an easy target, as there were air-aircraft guns near the dam and many enemy fighters based near it. The attacks began on 23 June and continued until 27 June. During that period, 670 Navy Marine, Air Force, and some South African aircraft, both ground and carrier-based, took part in the assault on the dam, flying 1,514 sorties.

Navy and Air Force Combine Efforts in Attack on Suiho

On the first day, the Navy sent 35 Grumman F9F Panthers on missions to suppress the anti-aircraft guns protecting the dam. 12 AD Skyraiders from the USS Boxer began dive-bombing runs. Their targets were the generating stations at the dam’s base rather than the dam itself. 23 Skyraiders from the Princeton and Philippine Sea also attacked, dropping 81 tons of bombs in a little over two minutes.

The Air Force also participated in the attacks, flying 79 sorties by F-84 Thunderjets and 45 by F-80 Shooting Stars. Suiho was not the only target that day. Altogether, UN aircraft attacked 13 key electric power plants in Korea.

The attackers did have the advantage of surprise, as there had been no other attacks on Suiho before then. Attacks later that year encountered much higher levels of anti-aircraft fire, leading some pilots to say the flak was as heavy as what they had seen over Berlin in WWII.

Reconnaissance photographs after the June attacks showed they had achieved military success. Eleven out of 13 electrical power stations were destroyed. North Korea lost 90% of its electricity production capacity, and the entire country was in a blackout for two weeks.

Political Concerns Persist After Successful Attacks

Despite the positive military results, the attack on Suiho caused political problems.

In the United Kingdom, the Labour Party opposed it, stating that it risked starting a third world war. The situation was different in the United States. Many Americans complained to President Truman that they should not have waited for two years before attacking the dam.

Lacking a consistent stance on the war, the U.N. could not convince the Communists to agree to a truce.

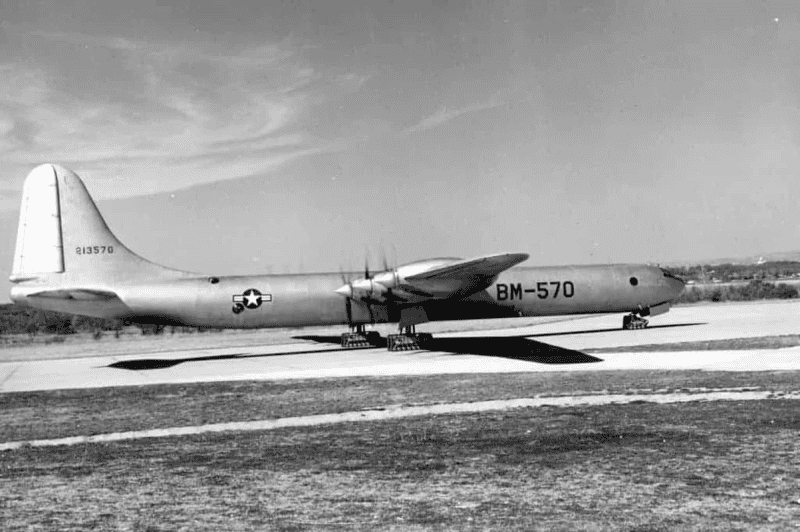

Heavy Bombers Chosen for Second Attack

The war continued in the months after the attacks, and negotiations were unsuccessful. When photos showed that the Communists were rebuilding some of the turbines, the Americans decided to attack Suiho again, this time with B-26 and B-29 bombers. The obvious advantage of the heavy aircraft was their ability to carry more bombs. Planners set 12 September for the attack. This time, however, they would not surprise the Communist forces.

Bombers Faced Extensive Reinforcements of Defenses

They had heavily reinforced the area around the dam, but the U.N. allies considered another successful strike on Suiho the key to stopping the war, so the plans proceeded. Since June, the Communists had increased the number of anti-aircraft weapons near the dam to 786 artillery guns and 1,672 automatic weapons. They also installed 500 powerful searchlights, many with radars or sound-controlled mechanisms that could detect planes and direct the lights at them. The search beams could reach up to 30,000 feet.

On the night of 12 September, the B-29 crews faced more than just fire from the ground. Many MiG fighters were waiting at nearby bases across the Yalu River in Chinese Manchuria. The U.N. forces were not allowed to attack across the river, so the Communist fighters were free to take off and engage the B-29s. Sixty B-29s took part in the mission, taking off from Okinawa, Japan, to attack the strategic targets at the base of the dam. As they flew west at about 25,000 feet along the river, they were hit by heavy flak and enemy aircraft.

Bud Farrell, a gunner on one of the B-29s, described the mission: “From that point at the I.P. to the target and ‘Bombs Away,’ there were continuous flak bursts around us, perhaps thousands within sight like a very long string of firecrackers going off in your face and all seeming closer in the dark than they really were, searchlights scanning from both sides of the river trying to find and lock on us.”

Following their bomb run, the aircraft faced another challenge. They had to make a sharp left turn immediately after dropping their bombs to avoid flying over Chinese Manchurian airspace, barely a half mile from the dam.

Mixed Results Following Bomber Attack on Strategic Targets

One B-29 was shot down during the attack, and several others suffered serious damage to the crews and aircraft and had to land at alternative airfields in Korea. Aircrews initially reported that they had struck many of their targets at the base of the dam. However, photos on 12 October showed the complex was operating at a limited capacity.

UN Allied planes again attacked Suiho in February 1953, but this did not achieve the results planners had hoped for.

The Korean War continued until 27 July 1953, when both sides signed an armistice but not a formal peace treaty.