They say that heroes live among us.

They are the invisible heroes. The quiet heroes. The ones whose deeds go unnoticed.

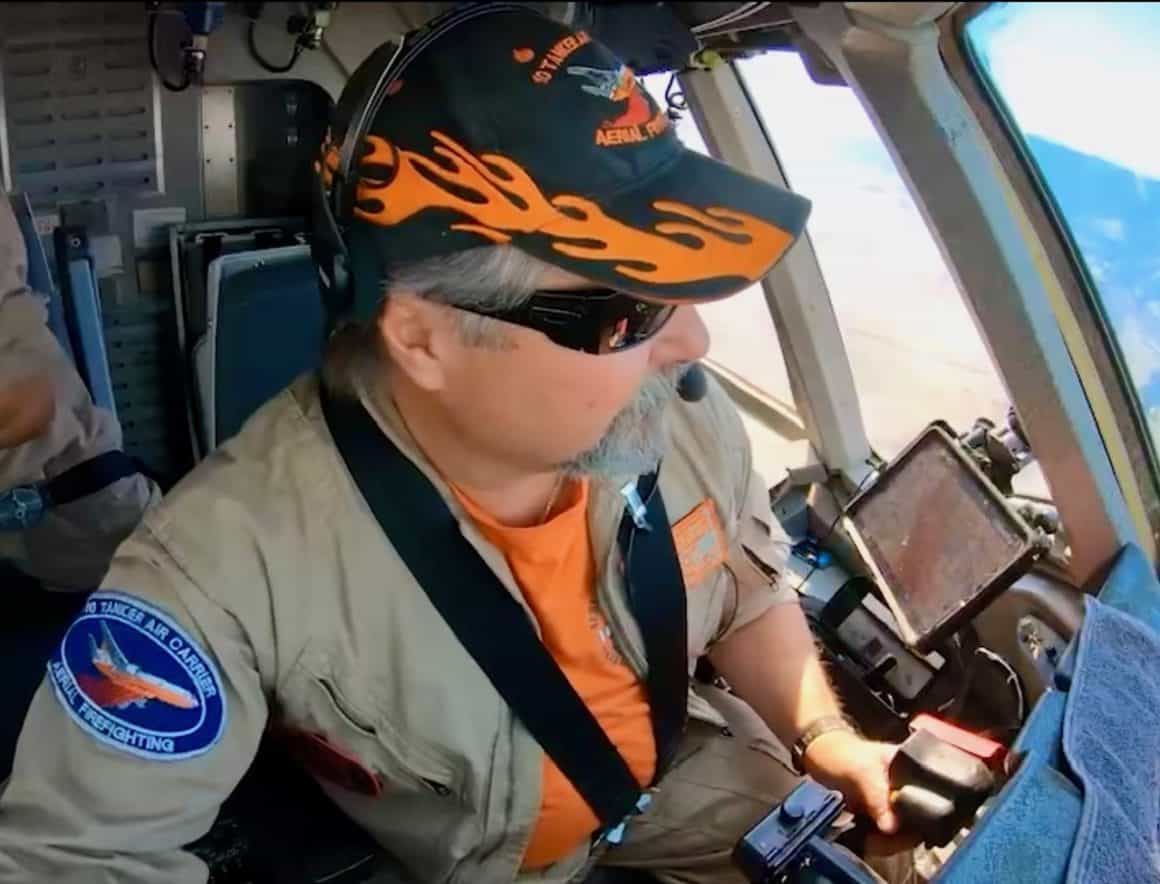

One such hero is RK Smithley, an aerial firefighter with an outfit called 10 Tanker Air Carrier. I had the extreme honor of sitting down with him recently to talk about what he does on a daily basis. I am positive he wouldn’t want to be called a hero, but in a very real sense, he is precisely that.

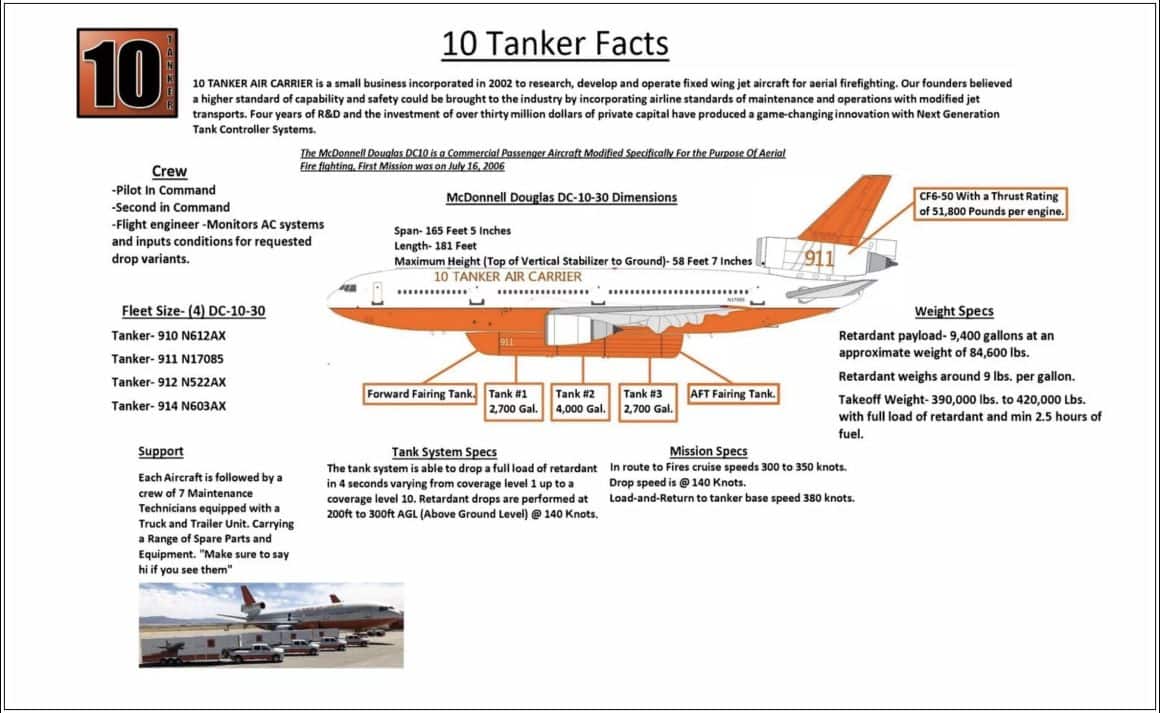

Based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, 10 Tanker Air Carrier operates a fleet of four DC-10 aerial firefighting aircraft, each modified into a very large air tanker (VLAT) capable of delivering 9,400 gallons of fire retardant to combat wildfires across the United States and beyond. At the controls of one of these aerial giants is Captain RK Smithley, a veteran pilot whose journey from a small town in western Pennsylvania to the cockpit of a firefighting DC-10 is a tale of passion, precision, and purpose.

With a career spanning 25 years at World Airways, a stint in corporate aviation, and now 11 years with 10 Tanker, Smithley’s story is one of the most captivating I’ve ever heard. I sat down with him to dive into his roots, the adrenaline-fueled world of aerial firefighting, and the unique challenges of flying a DC-10 over raging wildfires.

His account, rich with technical detail and personal anecdotes, paints a vivid picture of life on the fire line. This is his story.

Smithley’s Background and His Journey into Fire Aviation

AvGeekery: Can you tell us about your background and where you’re from?

RK: I’m from Ligonier, a little place 50 miles east of Pittsburgh, out in Pennsylvania’s Laurel Mountains. It’s a small town, the kind where everybody knows your name. I don’t live in Albuquerque full-time; 10 Tanker flies its crews from their homes to wherever the airplanes are. I’d say half our guys live in the East, half in the West.

I live near Bristol, Tennessee now, moved there about a year ago from the Atlanta area. I worked for World Airways out of Peachtree City, Georgia, for many years. So I’m kind of a Delta snob—million-miler status, partly thanks to World Airways and partly 10 Tanker. We live wherever we want, and when it’s time to work, we book our own commercial flights, hotels, and rental cars. No travel department here; we do it all ourselves.

AvGeekery: Can you walk us through your aviation journey and how you ended up at 10 Tanker?

RK: I’m an Embry-Riddle grad, Class of ’83, Aeronautical Science. Started at World Airways in ’89 and worked there for 25 years. World was the primary carrier for military troop and cargo movements. It operated a fleet of DC-10s, MD-11s, and 747s. I started out in the DC-10, flew it for ten years, and then flew the MD-11 for 15 years. Never got to the 747.

I think we had four DC-10s when I joined World. I came off the 10 in 1999, but we operated them for another 5-7 years. We had also taken on new MD-11s from Douglas, sometime around ‘92 or ‘93. So we ended up with about 15 MD-11s and four 747s. The 747s were all freight. The MD-11s were both passenger and cargo. The DC-10s were combi DC-10-30s. Believe it or not, at various points in the year, we’d convert them from passengers to cargo and cargo to passengers. I was all set to upgrade to the 747 once World got a fifth one, but it ended up getting canceled, so I stayed on the MD-11.

When World folded in 2014, I became chief pilot for a corporate 135 operation in Kennesaw, Georgia. They hired me to take them to 121. It was fine, the commute was great –30 minutes– but I wasn’t happy. Too much work, not enough joy.

Then, buddies of mine from World who’d joined 10 Tanker told me about bombing fires from 250 feet at 170 miles an hour in a DC-10. I thought, “You’re kidding.” My replacement as chief pilot at World was already here, and he sold me on it. Eleven years ago, I joined 10 Tanker, and I haven’t looked back.

A Day in the Life of a DC-10 Aerial Firefighting Captain

AvGeekery: Take me through the process of being called up for duty. How does that work?

RK: If it’s outside of a normal shift, we will get the call and deploy. Again, we don’t have a travel department, so we make all the arrangements, from booking flights to accommodations and rental cars.

AvGeekery: So right now, you’re at a hotel in Albuquerque, which is where 10 Tanker is based. Tell me what a typical day looks like for you.

RK: We basically show up at a tanker base at whatever time they want us there—typically 0900, but if we’re working an active fire, it could be 0800 or even 0700 for what’s called a campaign fire, those massive blazes that cover thousands and thousands of acres and burn for days on end. The planning starts with a base briefing within the first hour of duty. They’ll cover what’s happening in the fire world, what they’re anticipating for the day, and where the different assets are located—other tankers, leadplanes that guide our drops, and air attack platforms, which are like forward air controllers orbiting overhead, managing the airspace above the fire.

Our four DC-10 aerial firefighting aircraft at 10 Tanker are spread out across the West. Right now, for example, there’s one in Pocatello, Idaho, another in Moses Lake, Washington, a third in Santa Maria, California, and mine’s here in Albuquerque. We stay connected with the other crews, chatting via text to give each other a heads-up on what we’re seeing out there. When we’re ordered to a fire, we send emails to all flight crew members and management, detailing where we’re going, where we’re at, and where we’re expected to reload with more retardant. There’s a lot of communication going on—it’s critical to keep everyone in the loop.

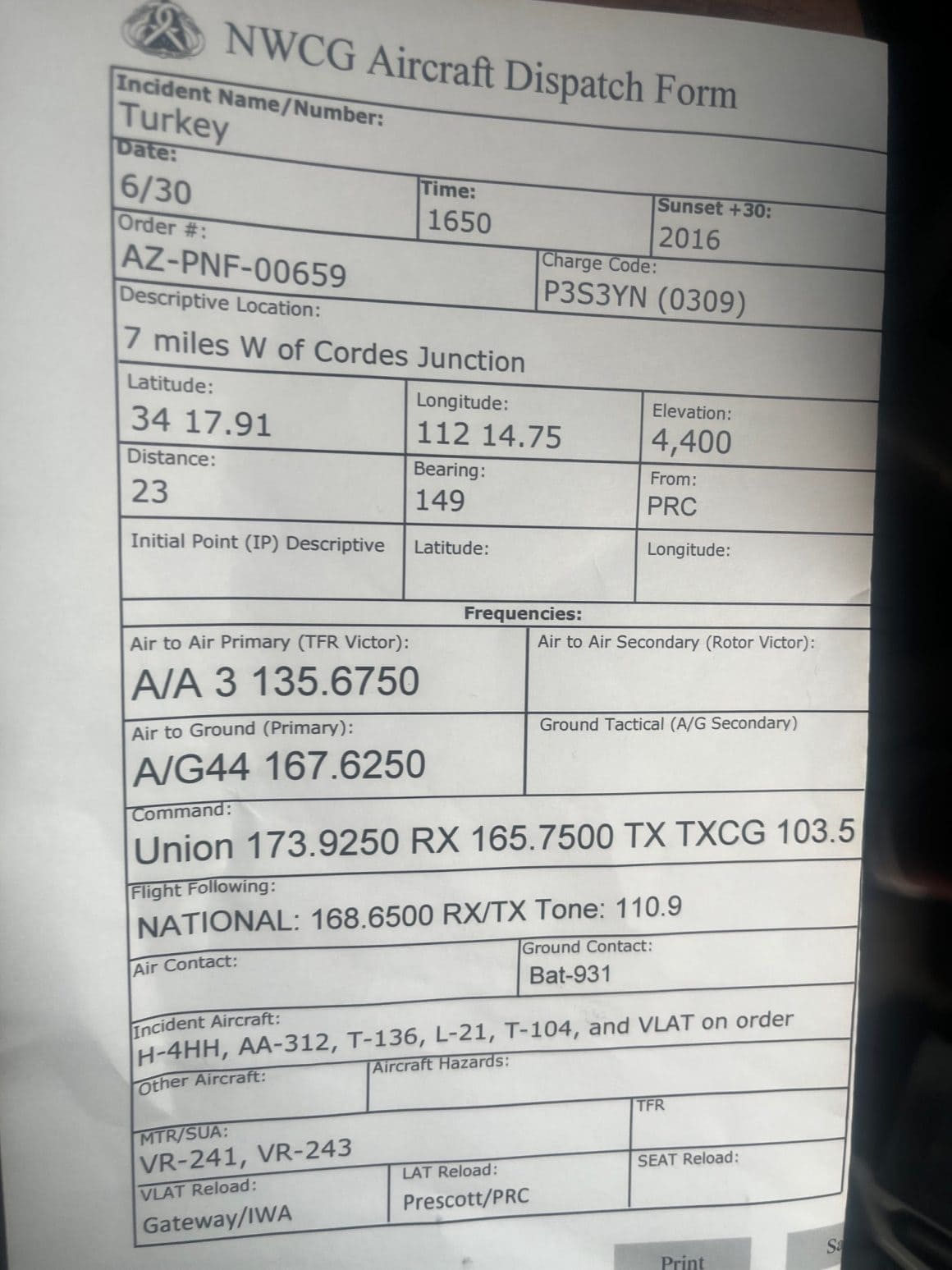

While we wait for the call, the airplane sits ready, and so does the flight crew—captain, copilot, and flight engineer. When the phone rings, the base hands me, as the captain, a piece of paper—the dispatch order.

It’s got everything we need: latitude and longitude coordinates, a descriptive location of the fire, and sometimes hazards like wires, cell towers, or windmills. It’ll note if structures are threatened or specifics about the terrain, like when we were working the Oak Ridge fire near Gallup, New Mexico, which was technically just across the border in Arizona, on Navajo Indian land. That detail’s included, though it doesn’t change our approach.

The order also has contact information and, most importantly, our operating radio frequencies. It lists who’s been ordered to the fire—other tankers, leadplanes, air attack—though it’s not always a complete list, so we’ll ask if we need to confirm who’s out there.

Once we get that paper, we head to the airplane and plug the coordinates into the navigation systems, which take nine minutes to spool up and come online. Meanwhile, the ground crew is loading 9,400 gallons of red retardant into the three external tanks on the belly of the DC-10—what we call the “canoe.” That process takes 15 to 20 minutes, depending on the base’s setup.

About 20 minutes after getting the order, we’re starting engines and heading to the fire. From Albuquerque, we could be dispatched anywhere. The other day, we were working Oak Ridge near Gallup, got back to base, and thunderstorms rolled in, parking us for a bit. When a weather corridor opened, we were ready to go back, but the base called on the radio: “Hey, we’ve got a divert for you.” They sent a new order, redirecting us to a fire just south of Prescott, Arizona—a 50-minute flight one way.

Another example: we recently started a shift in Mesa, Arizona, working a fire near St. George, Utah, reloading at Mesa Gateway. On the second run, they asked, “Do you have fuel to get to Pocatello?”

I said, “Yeah, why?” They told us to recover there—they were done with us for the day.

Flexibility is everything.

RK Smithley

I think they were spreading out the assets since two DC-10 aerial firefighting aircraft were already at Mesa, and they wanted one in the Great Basin area. So, we spent one night in Pocatello before relocating to Albuquerque for the Oak Ridge fire. You never know where you’ll end up at the start of the day, so we always carry our bags with us. We might not check out of the hotel, but the room’s empty, and our stuff’s on the airplane in case we’re relocated.

That’s the reality of this job—flexibility is everything.

AvGeekery: You said when you get dispatched, you get a list of all confirmed assets heading to the fire. What exactly do you look for?

RK: Most critically, we cannot drop without a leadplane, as DC-10s are not initial attack qualified—unlike lighter tankers such as MD-87s, C-130s, BA-146s, and RJ85s, which can drop with only air attack oversight. We’re actively working to change that, though. We conducted extensive training during the offseason to prepare for initial attack certification for the DC-10.

For now, we rely on leadplanes, but initial attack air tankers can operate with just an air attack platform providing aerial supervision, communicating directly with air attack about their objectives. Meanwhile, air attack coordinates with the incident commander on the ground—if there is one. On new fires, ground crews often haven’t arrived yet, so there’s no one to coordinate with on the ground.

The air attack platform, typically a Rockwell 690, orbits above the stack, though some operators have begun using Pilatus PC-12s or even Citations. They manage the temporary flight restriction (TFR) area, overseeing the entire operation. The United States Forest Service (USFS) uses KingAir 250 GTs for leadplanes, and CAL FIRE uses the OV-10 Bronco for both lead and air attack.

If neither the air attack nor the leadplane is airborne, we don’t launch. We coordinate with the base to ensure the lead is in the air, giving them a 10-minute head start to the fire. Even if they’re on the ground and say they’re preparing to take off, we wait until they’re airborne—mechanical issues could delay them, and we don’t want to arrive first and waste fuel circling. Our DC-10 external tank system is not certified to land loaded, unlike many other tankers.

If we can’t drop, we’d have to jettison the retardant safely—but only if there’s no lead at the fire and no other nearby fires with a leadplane we could divert to. So once we’re airborne, we need complete assurance that we can reach the fire and make the drop.

That’s why it’s crucial to see those assets listed on the dispatch sheet. If they aren’t, we always confirm the Lead is en route to the fire and where they are coming from, so we can coordinate our arrival time. It helps to know if there’ll be four other tankers and a bunch of S2s, especially when working with CAL FIRE in California. If it’s going to be a busy fire with a lot of aircraft—a real gaggle—you might add extra fuel because you’ll likely be holding for a while before your turn to drop.

Go-Time: Flying the Mission

AvGeekery: Who’s on board the aircraft with you on a mission?

RK: Our missions require a captain, a copilot, and a flight engineer. These are not MD-10s. These are true DC-10s with a flight engineer.

AvGeekery: You’ve got your orders, you have the asset sheet, you know where you’re going. Now it’s go-time. What’s it like flying a mission? Can you share some of the details and what goes into making a drop happen?

RK: We enter the temporary flight restriction (TFR) area—picture a red circle on a map, like at a NASCAR race—at 170 knots, configured and slowed down. DC-10s aren’t initial attack qualified, unlike lighter tankers such as MD-87s or C-130s, so we rely on a leadplane to guide our drops.

At 12 miles out, we call: “Lead 7-5, Tanker 910, 12 east.” The lead assigns us an altitude, altimeter setting, and our position in the stack—maybe we’re first, maybe fifth. On busy fires, we might hold at an Initial Point (IP), 10 to 20 miles from the fire, named something like “Station IP” at 7,000 feet. We circle in left turns, listening to other aircraft on the radio, though heavy smoke can obscure them, so we lean on radio chatter for situational awareness.

We monitor FM air-to-ground radios 50 to 60 miles out to gauge the fire’s pace, picking up altitudes and altimeter settings, allowing us to descend to the entry altitude before arriving.

Air attack platforms—Rockwell 690s, Pilatus PC-12s, or sometimes Citations—orbit above in right turns, acting as forward controllers, while we maintain left turns unless cleared for a right turn due to the drop path. They coordinate with ground incident commanders, who rarely speak to us directly; instructions flow from the ground to air attack, then to the leadplane, and finally to us.

It’s a tightly choreographed process. For campaign fires—massive blazes spanning thousands of acres over days—an IP is usually established. For new fires, there might not be one, so we hold wherever directed until the lead is ready.

Once cleared, the leadplane guides us, detailing the drop zone and hazards like power lines, helicopter dip sites, or cell towers. While we operate at different altitudes than helicopters or smaller tankers like S2s or RJ-85s, our DC-10’s wake is significant, so there’s a three-minute rule post-drop to let it dissipate, similar to the five-mile spacing at major airports like Hartsfield for heavy in-trail spacing. The lead may perform a “show me” run, flying low to mark the start and stop points, about a thousand feet below us.

On the Oak Ridge fire near Gallup, we were V-ing off structures for protection—laying a retardant line one way, circling back, and angling another to form a protective V. I’ve made five or six runs from a single 9,400-gallon load, boxing in assets like a cell tower or the Wilson Observatory above Ontario [California]. They’ll say, “Start here, stop at that two-track road,” and our system allows precise “start-stop” drops.

The retardant is red so we can see previous drops, letting us “tag” the end of another tanker’s line and extend it—straight or angled—to build walls around the fire. We’re not extinguishing; we’re slowing the fire to give ground firefighters, who have the toughest job, a chance to control and extinguish it.

We might drop in the same area as the prior tanker or on the opposite side if their objective is complete. We think in terms of the fire’s head, flanks, and heel for situational awareness. My critical task is maintaining a consistent altitude—say, 250 feet—at 147 knots with a 60,000-pound fuel load for range (one hour out, one back, one reserve). With 85,000 pounds of retardant exiting in as little as five seconds, it takes constant elevator inputs and stabilizer trim to hold that altitude. A climb from 250 to 500 feet makes the line wispy, and the lead or air attack will call it out: “What the heck happened to that?”

Coverage levels are tailored to terrain. On Oak Ridge, in Gallup’s high desert, we used a lighter setting for grass—around 700 gallons a second, coverage level three or four—versus 950 gallons a second for heavy timber at level six or eight, which shortens the line but ensures thicker coating.

We coordinate with the lead during their “show me” run: “At coverage level eight, we won’t reach that road. Want a six?”

They might respond, “Yeah, six gives us 11 seconds to hit that point,” or stick with eight and let the next tanker extend.

It’s a blend of science, tactics, and constant communication to deliver that retardant exactly where it’s needed, every time.

AvGeekery: What’s the process of preparing and loading the fire retardant slurry onto the aircraft?

RK: When we get a dispatch order, the first thing we do is check the fuel load and the fire’s location to plan our approach. The DC-10’s got some unique constraints that drive our decisions.

For instance, it’s not certified to land with a load of retardant, and believe it or not, it’s also not certified to pressurize with a load onboard.

So, we’re flying to the fire unpressurized, which limits our altitude. We typically operate in the 11,000 to 13,000-foot range if we need to clear mountains, using supplemental oxygen. Since we don’t use full-face masks, we’re limited to a maximum altitude of 18,000 feet with that setup. The DC-10 can’t pressurize until the load is gone. It just wasn’t certified to do that. Once it’s gone, you can go to FL280.

We also have a limitation where we can’t certify RVSM [Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum], which caps us at 28,000 feet even after dropping, though we can climb that high on the way home if needed.

For a long dispatch—say, a 500-mile trip—it sometimes makes more sense to fly high and fast, empty, to save fuel, then land at a base closer to the fire, refuel, and load the retardant there. That’s happened three times in the last week across our fleet.

When we decide to load at a base, we confirm the fuel load—typically 60,000 pounds for a one-hour outbound leg, one-hour return, and an hour’s reserve—and ensure it’s good for the mission. Once I, as the captain, give the go-ahead with “Yeah, you’re clear to load,” the ground crew gets to work. They plug three-inch lines into each of the three separate tanks on the bottom of the airplane—what we call the “canoe” hanging off the belly.

Those tanks hold 9,400 gallons of retardant, and loading usually takes 15 to 20 minutes, depending on the base. As soon as it’s done, we’re off and running, ready to head to the fire with a full load, unpressurized, and prepped for the drop. It’s a streamlined process, but every decision—fuel, altitude, load—ties into the mission’s demands and the airplane’s unique setup.

The Rules and Regulations of Fire Aviation

AvGeekery: So you’re on a six-day-on, one-day-off schedule. What does a typical shift look like for you and your airplane?

RK: My shift is 11 days, then a week off, then another 11. We’re training a new captain now to get us to two captains per airplane, with the hopes of achieving a two-week on, two off schedule. He’s a fire veteran, so we just need to teach him the DC-10. The airplane works six days, then gets a maintenance day for TLC. This includes tire and brake changes, MEL items, or planned inspections. The mechanics work really hard, and sometimes really late, to keep us flying, especially during busy seasons with seven-day coverage.

AvGeekery: How many drops can you make in a day, and are there FAA time regulations to which you must adhere?

RK: We’re governed by duty time and flight time limits, kind of like 121 operations in commercial aviation, but tailored to our unique mission. The maximum is a 14-hour duty day, and sometimes we push right up to that limit. If we start at seven or eight in the morning and go until dark, we’re hitting that 14-hour mark.

The rule is we have to complete our drops by sunset plus 30 minutes, but we can fly back in complete darkness to get back to base within the flight and duty time rules. That’s how we end up with some late nights.

Within a 24-hour period, we’re capped at eight hours of flight time. For the week, it’s a maximum of 36 flight hours over six days, and we sometimes get close to that or even encroach on it. If we exceed those limits, there are compensatory measures—like extra rest—but that gets into details that are a bit too complex. Essentially, we stick to 36 hours in six days as our hard limit.

As for drops, the record for a DC-10 in a single day is 12, and let me tell you, that’s pushing it. It’s like Southwest turning 737s—fast, efficient, and a little mind-blowing for an airplane this size. It’s almost like a NASCAR pit stop in slow motion, with a ton going on.

We’re loading 9,400 gallons of retardant, fueling up, and the mechanics are doing the walk-around for us since we don’t bring steps to the airplane every run. They’re on the interphone, communicating the whole time, checking the aircraft so we don’t have to climb out of the cockpit.

The most I’ve personally done is nine or ten drops in a day, and that’s only possible when the fire is close, like 30 minutes or 30 miles away, say, the Cajon Pass fire, just 18 miles from our San Bernardino base. You’re back and forth, reloading nonstop, and those are rough days for the whole crew, mechanics included. Nobody gets a break.

Flying unpressurized adds to the challenge. The airplane’s air-conditioned, but when it’s 100 degrees on the ground, it gets hot, and that takes a toll. Combine that with the intensity and adrenaline of constant fire drops—flying low at 250 feet, 147 knots, banking hard—it’s exhausting.

Avgeekery: And no flight attendants to bring you drinks or snacks, either!

RK: (laughing) Nope! But the bases do a great job of keeping us fed. We’ve got a cooler onboard with water, drinks, and snacks. They’ll toss lunches into a five-gallon Home Depot bucket, which we drop out the door and reel back up. Believe it or not, we’ve got a picnic table strapped down on the main deck, which is basically the same as a gutted UPS or FedEx freighter without the roller mats, where we can sit for a few minutes, eat, and stretch our legs away from the cockpit. Those brief moments help, but on a 12-drop day, it’s relentless. You’re running on fumes by the end, but it’s what we do to get the job done.

The DC-10: An Old Gal, but a Nimble Beast

AvGeekery: Does the plane handle differently when loaded versus empty when you’re flying back at FL280?

RK: Oh yeah, you definitely feel the difference, and it’s a big one. When we’re loaded with 9,400 gallons of retardant, we’re at 420,000 pounds, which is still 160,000 pounds under the max gross weight of 572,000 I flew in the DC-10-30s at World Airways. That gives us an incredible power-to-weight ratio—better than most air tankers out there, maybe except the Dash 8Q-400. All that thrust makes the DC-10 feel alive, like you’ve got power to spare. Power is life, you know.

But to your point about altitude, we don’t often fly high. For instance, after a drop on the Arizona fire, we came back at 17,500 feet VFR, heading northeast. We rarely get into the flight levels because it takes a lot of fuel to climb up there, and we have to weigh that against the winds and the length of the flight.

If it’s a long haul, sure, going higher might give us a smoother ride and better fuel efficiency, but New Mexico and Arizona right now? It’s constant low-level turbulence from the heat, and we’re dodging virga all the time. On the Oak Ridge fire near Gallup, we got beat up pretty good by the rough air. One time, we parked the airplane when the weather was closing in, and me and the trainee were like, “We’re done.” Good call, too—winds were gusting to 58 knots not long after. It got strange out there.

The biggest difference in handling comes during the mission itself. The DC-10 is an amazingly nimble airplane for its size, thanks to the leading edge slats—Douglas calls them slats, Boeing would call them leading edge flaps—and spoilers that help us roll.

I’ve never flown a fighter, but some of the videos you’ll see of us, we’re horsing this thing around like a big fighter jet. Picture coming down the side of a mountain in a turning drop, on the tip of the spear, trying to lay retardant exactly where the ground crews need it. We’re not doing it for show, but sometimes the terrain demands it. You’re yanking and banking hard, evaluating escape routes—what if an engine quits?—because a go-around is always an option.

There are places we can’t get into, where single-engine tankers or helicopters shine, but we can handle most anything else. We’re the biggest tool in the toolbox, delivering 9,400 gallons compared to a large air tanker’s 3,000. The air attack and leadplanes decide when to call in the VLAT, and we make it count.

On the way back, empty, the plane feels lighter and more responsive, but we don’t vary speed much—145 to 149 knots, usually 147, with a typical fuel load of 60,000 pounds for range: one hour out, one hour back, and an hour reserve to divert somewhere like Roswell if Albuquerque’s weathered out. For the Arizona run, we added 8,000 pounds of fuel for comfort with storms around. The lighter weight makes the plane more agile, but we’re still dodging turbulence and managing the mission’s demands. It’s a different beast empty, but the DC-10’s power and agility make it a joy to fly, loaded or not.

AvGeekery: With DC-10s fading from commercial use, is it hard to get parts for the 10 Tanker fleet?

RK: Yes and no—it’s a mixed bag. The good news is that the Air Force’s decision to park their KC-10 fleet, which included 59 DC-10s, has been a real boon for us at 10 Tanker. They’re starting to release parts from those airframes, and we’ve already bought engines from them.

I’ve got a couple of buddies out at Travis Air Force Base in Sacramento who’ve been involved with the KC-10s, and they’ve confirmed the parts are becoming available. FedEx’s DC-10 and MD-10 fleet is another resource we tap into. In fact, 10 Tanker is likely going to buy some KC-10s outright just for parts.

I’ve heard the Air Force is keeping around 20 KC-10s in operational ready reserve, though I’m not certain of the exact number. That still leaves over 30 airframes available for us to pull structural parts from, which has made components more plentiful than they used to be.

The cool thing about our fleet at 10 Tanker is that we’re flying some of the last DC-10s ever built. Three of our four airplanes are 1987 and 1988 models, originally flown by Thai Airways, Japan Air System, and Northwest. The foundations of 10 Tanker were rooted with Omni International, principal owners out of Tulsa, who parked their DC-10s years ago. Those ended up becoming our tankers.

Our oldest bird, a 1975 model, is what we call our antique—an ex-Continental ship that started with Finnair—but it still flies and runs like a champ. These airframes are relatively low-time, especially compared to my days at World Airways, where we’d log 250 hours a month. At 10 Tanker, we’re only flying 250 to 400 hours a year, though it’s intense, rigorous flying—low-level drops at 250 feet, yanking and banking hard over fires. That kind of work demands thorough maintenance, and our off-season inspections are no joke.

Our mechanics…I can’t say enough about them. They’re the unsung heroes keeping these planes airworthy. When our fire season wraps up in November, they dive into heavy checks at bases like San Bernardino or sometimes Albuquerque.

This past winter, Tanker 911 was in Oscoda, Michigan, at Kalitta for a C-check. Those guys work year-round, not just keeping the airplanes rolling during the season but doing deep maintenance to prep for the next year. For example, we got recalled to California in January—an extremely rare event—but our team was ready because of their meticulous off-season work.

The airframe I’m flying now has about 70,000 hours, which, in the grand scheme, isn’t bad for a DC-10. With the parts supply from the KC-10s and our maintenance program, we’re good to go for a while longer, keeping these old birds fighting fires with the best of them.

The 2025 Los Angeles Fires

AvGeekery: Can you tell us about that January call-up to the devastating Los Angeles fires? How does that process unfold when you get that unexpected call?

RK: You’re at home, maybe visiting family or just kicking back after New Year’s, doing whatever. Chief pilot sends out an email blast to all the crews: “Hey, we got a new fire in L.A. or SoCal. We may need to send one, two, or three airplanes—whatever we can manage.”

In January, it’s rare—only the second time in 10 Tanker’s history we’ve flown in the U.S. that month, the last being around 2013 before I joined. This time, we could only send two DC-10s because the other two were in heavy maintenance. One was completely torn apart in Oscoda, Michigan, and the other in San Bernardino was too deep into its checks to fly. But we had two birds in Victorville, just coincidentally there for tank calibrations, so they were ready to go.

You start mentally preparing to head to Ontario to pick up an airplane.

Then the phone rings, and Chief Pilot’s on the line: “Hey, can you go to Ontario and get Tanker 914 in Victorville? Get a crew together.” He’ll say, “I’ve got B and C lined up for copilot and flight engineer. You’re A, the captain. Coordinate with those two and let me know how soon you can get there.”

That’s how it goes—you drop everything, pack a bag, and start heading west. For me, it was a bit of a push. When the Chief Pilot first called, I was like, “Eh, it’s just after New Year’s. I don’t want to go to work.” But he said, “We may need two airplanes.” I told him, “If you get the second airplane, I’ll go.” Sure enough, they needed the second one, so I went. Chief Pilot himself took the first airplane, and I led the second.

It’s a scramble, but it’s what we do—roll with the punches to move an airplane and help people who need it, saving lives and property.

That SoCal mission was memorable, not just because it was January, but because of the impact. Those fires were small by our standards, about 12,000 acres compared to the 400,000-acre monsters I’ve worked. But they burned through 12,000 homes between the Palisades and the Eaton fires.

In our world, we get called for fires as small as a couple thousand acres, so 12,000 isn’t huge, but 12,000 homes? That’s massive. Flying over those black foundations, holding over what used to be people’s homes and, in some respects, their lives torn apart—it tears at you. It was one of the most poignant missions I’ve flown, not just for the urban devastation but because it was such an unusual event for us to be out there in January, something we’d only done once before in company history.

This kind of rapid response isn’t new for us. We’ve got an international presence, too. For years, I flew to Australia during their summer—our winter—for six years straight when I was new. We’ve done Chile in January or February, like two years ago, and Mexico, flying out of Laredo, Texas, into the Sierra Madre Mountains south of Monterey, the year before that. Those international call-ups work much the same: you get the word, you pack, you go. But that SoCal call in January? It stood out for its rarity and the emotional weight of seeing so many homes lost. It’s a reminder of why we do this—helping people when they need it most.

So You Want to be an Aerial Firefighter

AvGeekery: How does someone get into aerial firefighting? What’s the journey like for someone looking to join an outfit like 10 Tanker?

RK: Aerial firefighting is a tight-knit world, a club—way smaller than World Airways, where we had 500 pilots and crew. Here at 10 Tanker, we’ve got just 25 crew members, and across the whole country, there are only 35 big air tankers—BA-146s, C-130s, 737s, and our DC-10s–between the four different contract air tanker companies. That’s not counting the smaller S2s and C-130s used by CAL FIRE.

It’s an exclusive group, and you almost have to know somebody to get your foot in the door. That’s how I got in. I knew two guys from World Airways who’d jumped to 10 Tanker, and with my 3,300 hours of DC-10 time, it was a natural fit. They could teach me fire tactics, but I already knew the airplane. It’s tough to teach both fire and the aircraft from scratch, so you need one piece to start—either heavy jet experience or fire knowledge.

Take our new hire this year, for example. He flew Single Engine Airtankers, or SEATs, so he knows fire inside and out–tactics, lingo, procedures. He also flew a corporate 737, so he’s got jet time. We just have to teach him the DC-10.

On the flip side, when I joined, I was the opposite: a DC-10 guy with zero clue about aerial firefighting. I’d been a volunteer ground firefighter at 16 in Pennsylvania, but aerial tactics? No idea. It’s extensive—there’s so much to think about.

After your first year, you go to a school called NAFA—National Aerial Firefighting Academy. It’s a three-level course where you learn the tactics and lingo, and it really opens your eyes. From there, you can start working toward the left seat as a captain.

I made captain in my second year because they needed me to, with my 3,300 hours in the DC-10, but it took time to learn fire. Even now, 11 years in, I’ll hear something from a colleague and think, “Oh, I didn’t know that.” You’re always learning, just like in 121 operations.

If you’re coming in fresh, one path is flying air attack platforms, like a Rockwell 690, orbiting above the fire in holding patterns all day. Your right-seater, an aerial fire supervisor, doesn’t need to be a pilot but handles comms with incident planners on the ground. That’s a great way to learn fire operations and build experience.

Another route is crop dusting—guys come out of Air Tractor AT-802s, either learning fire through that or bringing some fire knowledge and learning the airplane. You’ve got to have one of those pieces—fire experience or heavy jet time—and knowing someone in the business is almost a must. It’s no secret, no discrimination; it’s just the reality of a small field.

A couple of weeks ago, at an airshow here in Albuquerque, I was doing tours of our aircraft when a guy flying 737s for a major airline came up to me. He thought aerial firefighting sounded incredible. And it is, but you’ve got to have a screw loose to choose this over the airlines, where you can make a lot more money flying point A to point B, like driving a bus with wings. We’re not getting rich, but we’re well taken care of.

The real payoff is when you see a row of houses you saved—that’s a level of accomplishment you can’t get flying passengers. It gets in your blood, just like ground firefighting did for me as a second-generation volunteer firefighter in Pennsylvania. I did that for 16 years, and now I’ve come full circle with aerial firefighting. Aviation’s in my blood, too, so combining the two? My blood’s pretty rich.

Our youngest captain is 27, and I’m thinking, “Why isn’t he at Delta, American, or Southwest?” He might go there someday, but he came from flying air attack and decided he wanted to fly a tanker. He’s getting it done. How long will he stay? Who knows—maybe he’ll retire at 60 or 65. We don’t have an age limit; one of our lead pilots is 70.

You can fly till you drop if you want, but I’ll tell you, this isn’t a game for old guys. I’m an old guy myself, and it wears on you. Eight legs a day, and you’re so beat you can barely eat at the hotel before crashing, hoping for a shower and some sleep before another eight-legged tour tomorrow.

Younger guys handle it better, but we old-timers still do it well. It’s a lot of work, and there’s a lot of boredom too—sitting at the base for days, especially early in the season, screwing around on Facebook, reading books, or shopping on Amazon. Then the phone rings, and your hair’s on fire. You’re moving to the airplane, and by the end of the day, you might be five states north.

It’s a different lifestyle—no epaulettes, no black plain-toed shoes, no herding flight attendants. I wear a 10 Tanker shirt, shorts, tennis shoes, and a Nomex flight suit, growing whatever facial hair I feel like. It’s freeing, but man, it’s intense. Once firefighting and aviation get in your system, you don’t want to leave. It’s a calling, and for those who want in, it’s about finding that one piece—jet time or fire knowledge—and making the right connections to break into this small, incredible world.

Aerial Firefighting is a Calling

AvGeekery: RK, it has been an absolute pleasure speaking with you today. I learned so much, and I’m sure our readers will, too. Any final thoughts or memorable moments you’d like to share?

RK: My favorite hat says “Yankin’ and Bankin’”—a phrase I dropped during a TV interview a few years back at a Salt Lake hotel, and some folks liked it so much they made hats for it. That’s pretty much what we do in these DC-10s—yank and bank, horsing these big birds around like fighters to get the retardant where it needs to go. We’re incredibly proud at 10 Tanker to be the largest tool in the Forest Service’s arsenal, carrying 9,400 gallons per drop.

There’s a place for every tanker out there—single-engine air tractors, helicopters, lighter tankers like the MD-87s or C-130s—but when they call us, we’re all in, no matter what. Doesn’t matter if we’re in New Mexico, California, or halfway across the globe in Australia or Chile. We’re dedicated to the job, giving it everything we’ve got.

What drives us is supporting the ground firefighters. Those guys and gals have the toughest, most important job of all, battling the flames up close. Our role is to help them get a handle on the fire, building those red retardant walls to slow it down and protect lives and property. That’s what it’s all about. This work gets in your blood, just like ground firefighting did when I was a volunteer in Pennsylvania.

I wouldn’t trade this work for anything—it’s a calling, and I’m proud to be part of it.

AvGeekery extends heartfelt thanks to Captain RK Smithley and the entire 10 Tanker Air Carrier team for granting us this insightful interview. We deeply appreciate your unwavering dedication and service to protecting lives and property across the nation.

To learn more about 10 Tanker, visit their website at 10tanker.com.