Hijackings weren’t uncommon in the late 20th century, as proven by EgyptAir Flight 648. But while many hijackers demanded money, a terrorist organization known as Abu Nidal demanded a free flight to Libya, or more passengers would die the longer it took.

In total, 56 passengers died during and after the flight, making it one of the most lethal hijackings in history. Here’s the story of EgyptAir Flight 648.

‘We Thought We Were Dropping From the Sky’

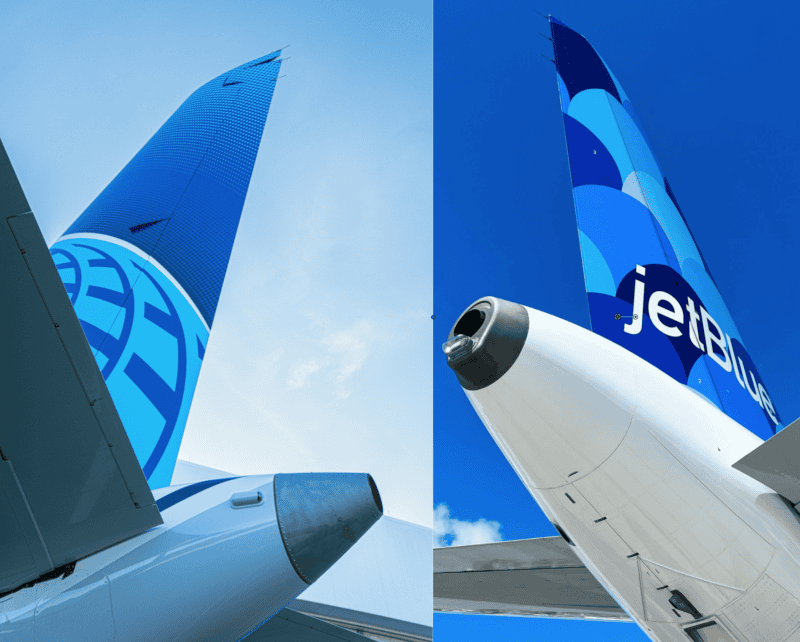

On 23 November 1985, EgyptAir Flight 648, a Boeing 737-266, departed Athens Ellinikon International Airport (ATH) in Greece en route to Cairo International Airport (CAI) in Egypt. On board were 87 passengers and six crew members. The flight was commanded by two 39-year-old pilots, Hani Galal and Imad Mounib.

At 2010 local time, ten minutes after the Boeing took off, three members of the Palestinian terrorist organization Abu Nidal brandished weapons and took over the flight. The identities of the terrorists were Omar Rezaq, Nar Al-Din Bou Said, and their boss, Salem Chakore.

At the start of the hijacking, Chakore would review all the passengers’ passports, ordering Palestinians and Egyptians to the back of the jet while Americans, Australians, Israelis, and Europeans to the front. Rezaq would enter the cockpit to demand that EgyptAir Flight 648 change course.

Methad Mustafa Kamal, an Egyptian Security Service agent, was next to give his passport to Chakore. Though the hijackers didn’t deem Egyptians as a threat to them, he was afraid they would find out he was still an air marshal. Rather than his passport, he swiftly took out his handgun, shooting and killing Chakore.

This led to a shootout between Kamal and Bou Said. Kamal and two passengers were wounded during the shootout. One of the bullets from Bou Said’s gun punctured the fuselage, prompting the pilot to descend to 14,000 feet so the passengers could still breathe.

One of the surviving passengers, Jackie Pflug of Houston, Texas, commented on the experience during an event in 2017:

‘We thought we were dropping from the sky…We were going to hit the ground and die’.

Pflug, Patrick Baker, and Scarlett Rogenkamp were three Americans on board.

‘Kill Someone Every 15 Minutes’

The hijackers initially demanded to go to Libya, but the descent caused the plane to burn through a lot of fuel. They then decided to divert to the closest airport, Luqa Airport, now known as Malta International Airport (MLA).

Galal informed ATC of the hijacked Boeing’s arrival ahead of time. Malta, however, didn’t want the aircraft to land and turned the lights off at the airport. The Boeing landed there anyway and did so safely.

Rezaq took over the hijacking, demanding refueling for continuation to Libya and a medic to be on hand for Chakore. He told ATC that somebody would die every 15 minutes until both demands were fulfilled.

Hours went by, and Rezaq would execute passengers one by one and throw them down a set of stairs to outside the aircraft. A few victims, though, did manage to survive and escape, having been found by Malta authorities and transported to a hospital.

The United States and Egypt would work together to plan a raid on the parked Boeing at MLA. Egyptian Unit 777 and the US Delta Force would disguise themselves as caterers to ambush the hijackers.

They arrived 90 minutes earlier than planned, scrapping the disguise idea and springing into action. The unit would plan to blow the door open and enter using non-lethal plastic explosives. The cavalry didn’t realize, however, that the hijackers placed a bomb underneath the fuselage. According to Dr. Abella Medici, the unit used more plastic explosives than necessary, which set off this bomb and suffocated many more passengers, as well as Bou Said, to death.

Rezaq’s Run From the Law

A total of 33 passengers and four crew members survived the EgyptAir Flight 648 hijacking. Rezaq was the only hijacker who survived following a confrontation outside the plane with Galal and an Egyptian militant. He was subsequently detained.

On 2 November 1988, Rezaq was found guilty on seven counts, including the killing of a few of the passengers on Egyptair Flight 648. While his initial sentence was 25 years, it was reduced to only seven due to a general amnesty, leading to his release in 1993.

Rezaq, however, was still wanted by the United States for killing a US citizen, that being Rogenkamp. Rezaq fled to Nigeria, where officials denied him entry because he did not have a passport. He was then handed over to the FBI and transported to the United States.

Rezaq is currently spending life in prison at the United States Penitentiary in Marion, Illinois.