Sunday was a difficult day for the United States Navy as two US Navy aircraft crash into South China Sea.

The separate incidents involved an MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter and an F/A-18F Super Hornet, both operating from the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN-68).

The crashes occurred roughly 30 minutes apart during routine operations, according to the US Pacific Fleet. The Sea Hawk is assigned to the “Battle Cats” of Helicopter Maritime Strike Squadron 73, while the Super Hornet belongs to the “Fighting Redcocks” of Strike Fighter Squadron 22.

Two US Navy Aircraft Crash Into South China Sea, Minutes Apart

The Pacific Fleet said the first incident took place at 1445 local time, when the MH-60R Sea Hawk went down while conducting routine operations from the Nimitz. Search and rescue teams from Carrier Strike Group 11 quickly launched recovery efforts and successfully retrieved all three crew members.

In its official statement, the US Pacific Fleet said,

“At approximately 2:45 p.m. local time, a US Navy MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter, assigned to the ‘Battle Cats’ of Helicopter Maritime Strike Squadron 73, went down in the waters of the South China Sea while conducting routine operations from the aircraft carrier. Search and rescue assets assigned to Carrier Strike Group 11 safely recovered all three crew members.”

Roughly 30 minutes later, at 1515 local time, an F/A-18F Super Hornet from the Fighting Redcocks of VFA-22 also went down.

“Both crew members successfully ejected and were also safely recovered by search and rescue assets assigned to Carrier Strike Group 11,” the Pacific Fleet added.

All five service members involved in Sunday’s incidents were safely recovered and are in stable condition aboard the Nimitz.

Final Voyage of a Legend

The USS Nimitz, the oldest active aircraft carrier in the US fleet, is on the return leg of its final deployment before decommissioning. The carrier, along with its escorts and embarked Carrier Air Wing 17, departed the West Coast on 26 March 2025 for what would be its last major operational tour.

Throughout the summer, the Nimitz operated in the Middle East, supporting US efforts to deter Houthi attacks on commercial shipping. The ship entered the South China Sea on 17 October, just days before Sunday’s incidents.

Both the Sea Hawk and the Super Hornet were conducting “routine operations” in a region of disputed waters that China claims as its own.

Beijing’s Response

China’s foreign ministry offered humanitarian assistance to the United States following the incidents, but also used the moment to criticize Washington’s continued military presence in the region.

The US Navy maintains its operations there to support regional allies and challenge China’s sovereignty claims, part of the ongoing effort to preserve freedom of navigation through one of the world’s busiest maritime corridors.

The timing of the incidents is notable, coming just days before President Donald Trump is scheduled to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Tokyo on 30 October.

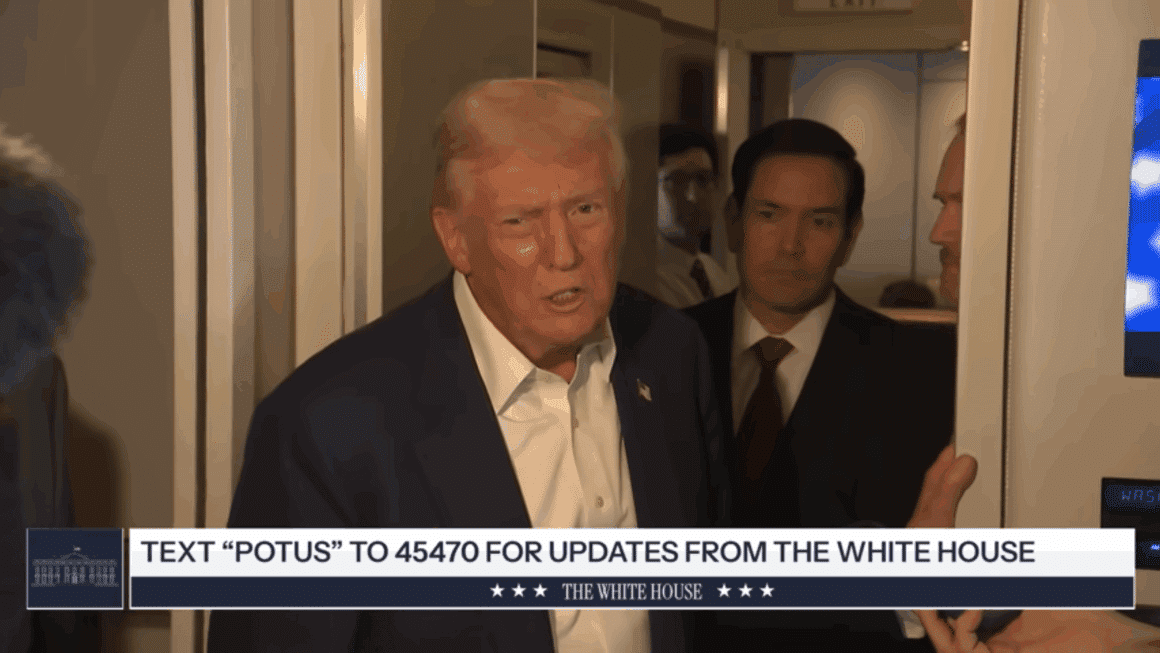

“Nothing to Hide,” Says President Trump

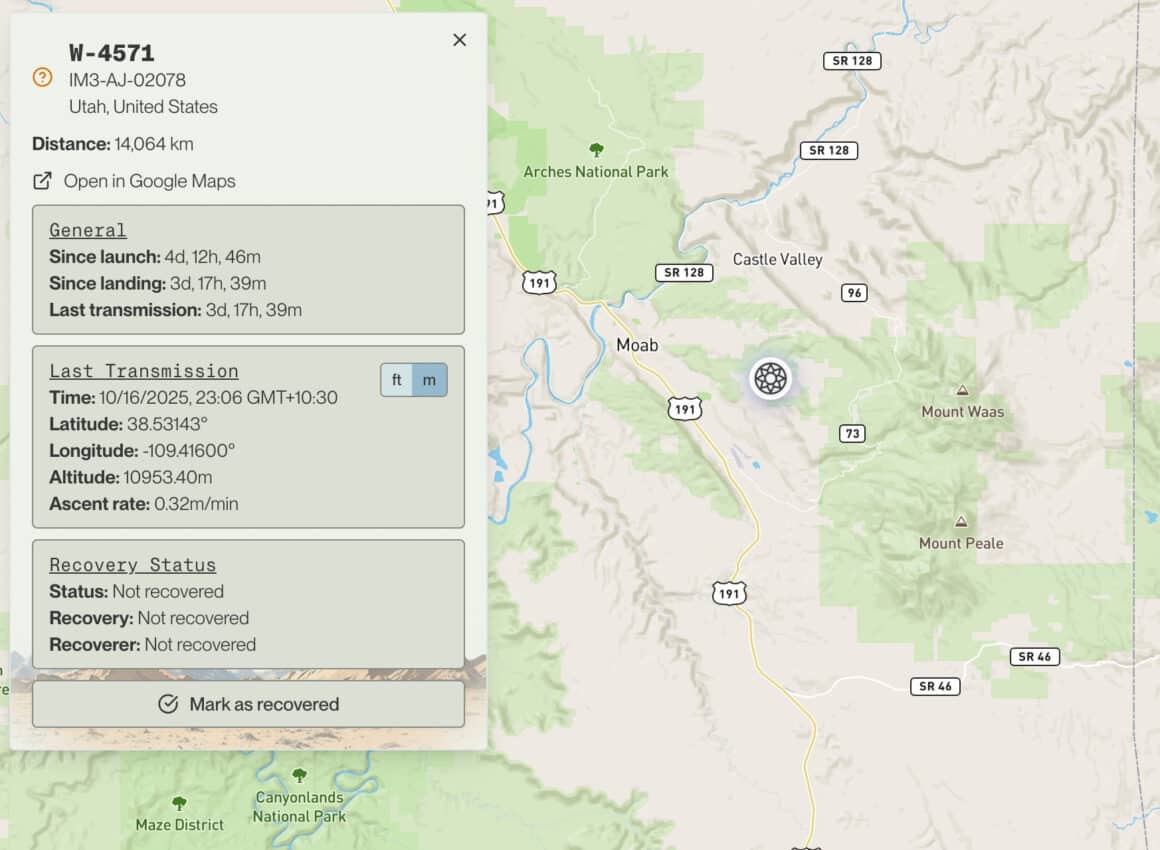

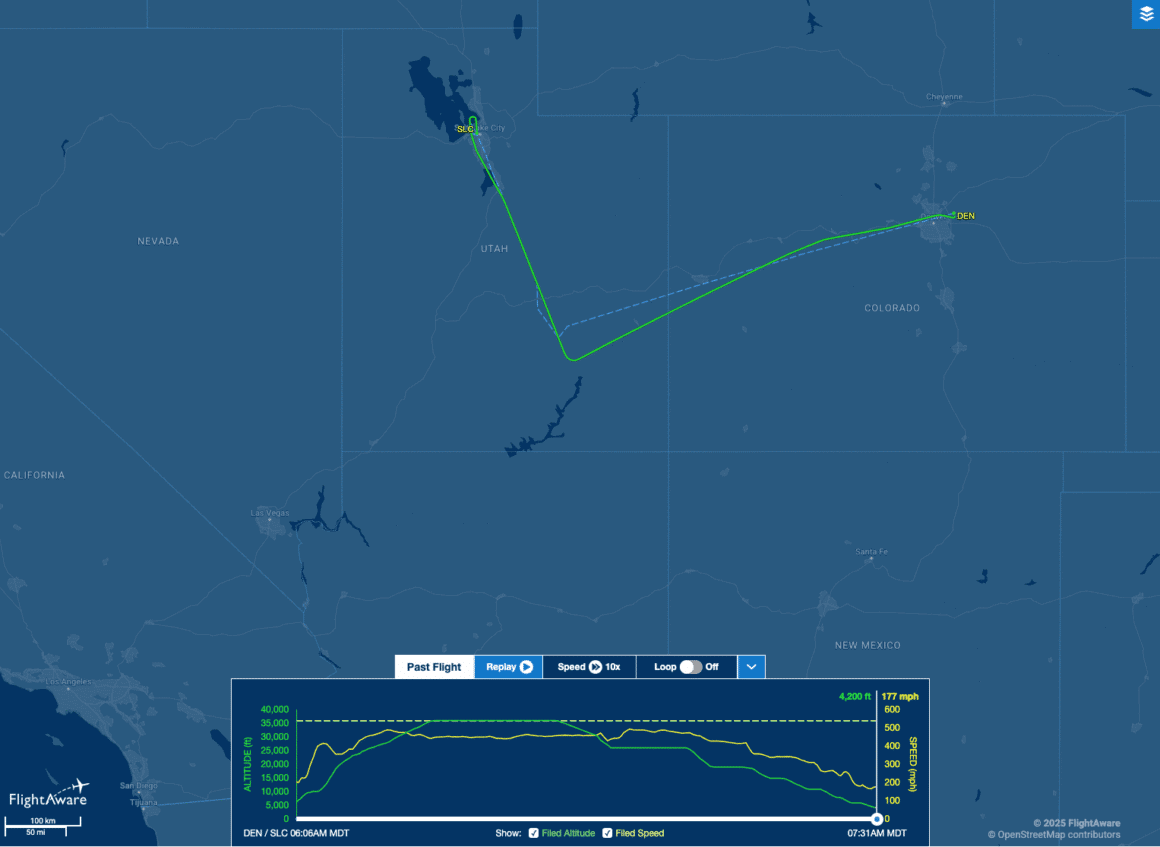

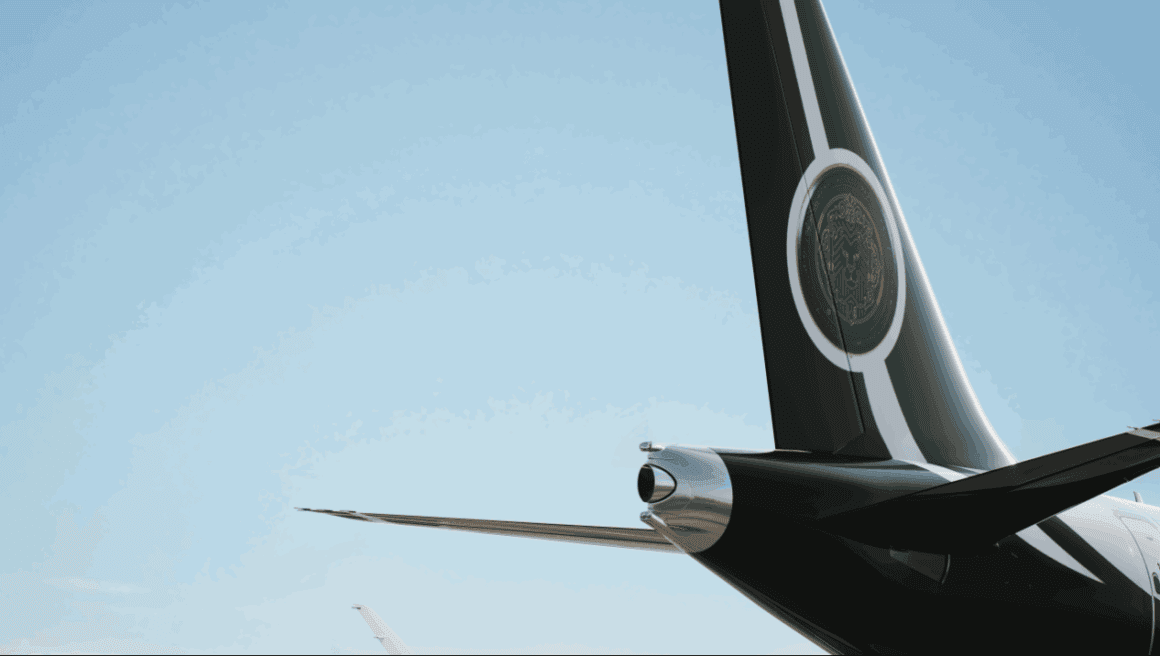

Speaking aboard Air Force One on Monday, 27 October, while en route from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Tokyo, President Trump said he had been briefed on both incidents and that foul play is not suspected.

“They’re going to let me know pretty soon,” Trump told reporters. “I think they should be able to find out. It could be bad fuel. I mean, it’s possible it’s bad fuel. Very unusual that would happen.”

The president added that there was “nothing to hide” and that the US Navy would release findings once the investigation concludes.

The Mighty Nimitz

Now in its 50th year of service, the USS Nimitz remains a floating symbol of American sea power. Measuring 1,092 feet from bow to stern and displacing approximately 100,000 tons when fully loaded, the carrier is powered by two Westinghouse A4W nuclear reactors that drive four shafts, giving it a top speed of more than 30 knots.

The ship typically carries more than 5,000 personnel, including both the ship’s company and air wing members. Nimitz-class carriers can operate continuously for up to 20 years without refueling.

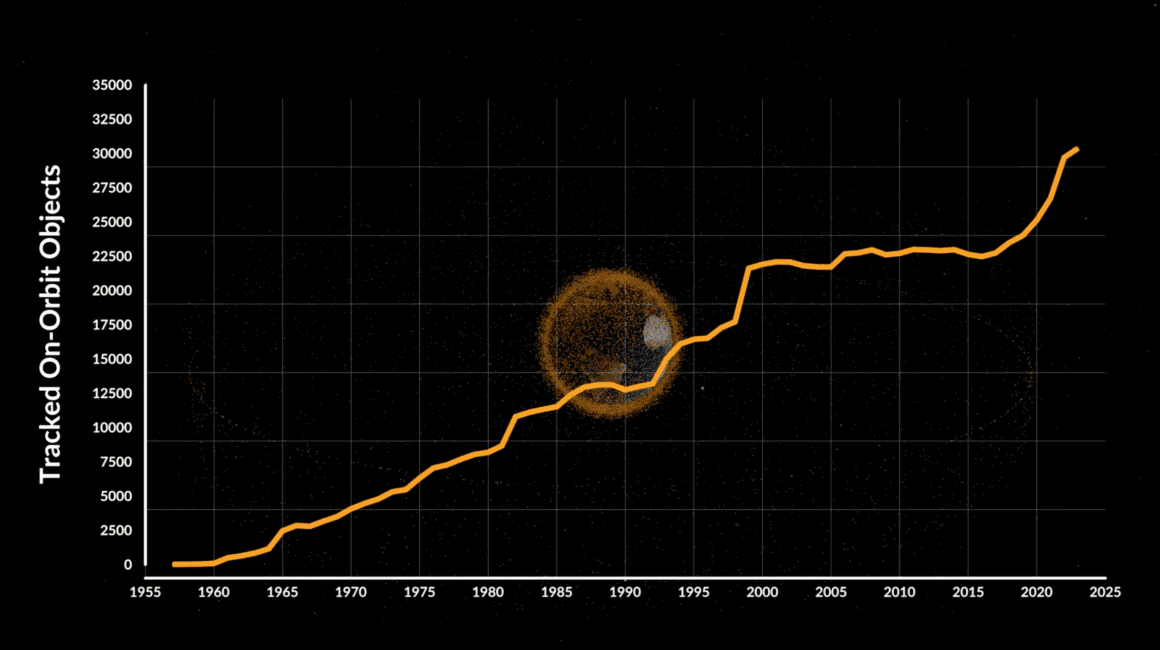

A Troubling Trend

Sunday’s loss marks the fourth F/A-18 incident for the US Navy this year.

In December, an F/A-18 from the USS Truman was accidentally shot down in a friendly fire incident involving the USS Gettysburg, a guided-missile cruiser.

In April, another Super Hornet slipped from the Truman’s flight deck into the Red Sea.

In May, a landing jet missed the arresting cables and plunged into the water.

Despite these setbacks, the Navy’s rapid response on Sunday ensured every crew member made it home alive.

Swift Action, Steadfast Sailors and Aviators

The US Navy’s efficiency and professionalism were on full display in the aftermath of both crashes. Within minutes, search and rescue teams from Carrier Strike Group 11 had located and recovered all five service members.

All personnel involved are safe, stable, and back aboard the Nimitz as the ship continues its journey home.

We salute the men and women of the United States Navy for their swift action, their courage, and their commitment to bringing every sailor and aviator home safely.