NFL and NBA team travel arrangements are highly dependent on logistics and cargo, as well as player comfort, performance, and playoff success.

Travel, especially air travel, often contributes to the success or failure of teams in the National Football League (NFL) and National Basketball Association (NBA). Teams in both leagues travel often throughout their seasons, requiring extensive planning and preparation.

While air travel is equally important for both leagues, each has different requirements and challenges in ensuring its trips are efficient and comfortable.

Logistics of Air Travel Key to Success of NFL and NBA Teams

The two leagues have very different travel needs, although both travel mainly by air. NFL teams play 16-game seasons, with one game per week, including eight away games. NBA teams play 82 games from October through May, with half being away games. If teams make their playoffs, they travel even more.

One of the biggest differences in air travel for the leagues is in the cargo they carry. NFL teams carry 53-man rosters, and NBA teams have 15 players. In addition, NFL teams travel with about 180 players, coaches, and staff members, while NBA teams take about 50.

NFL teams typically bring about 15,000 pounds of cargo to away games. This includes uniforms, extra shoes, specific gear for inclement weather, medical supplies, and sideline communication equipment.

NBA teams take about 2,500 pounds of gear to away games, but that can add up to more than 100,000 pounds over their long season. All of this must be ready for air travel, and equipment staff begin preparing months before the season begins.

Charters and Other Options for NFL and NBA Team Travel

Because of the passenger and cargo requirements, NFL teams usually fly on large, wide-body jets like Boeing 767s, 777s, or Airbus A330s. Many teams charter flights with American Airlines, Delta, United, and Hawaiian Airlines. However, this is not always an economical arrangement for the airlines.

A typical scenario for a team like the New Orleans Saints becomes problematic for airlines that don’t maintain large hubs near their cities. In this case, the chartered airline would have to fly their empty jet from a hub like Dallas to New Orleans and transport the team to an away game.

In this scenario, the chartered jet would sit unused for about 48 hours, then fly the team back to New Orleans after the game. Finally, the aircraft could fly back to its hub.

This would be expensive for the airlines, as they would only charge the teams for two to three hours of flight time for a short trip. In recent years, this system has led several airlines to cancel their charter service for NFL teams, forcing teams to find different travel options.

Some NFL teams, like the Miami Dolphins, have begun using dedicated charter companies. The Dolphins fly on Atlas Air’s 747-400, which is a good arrangement for the team as the jet contains enough first- and business-class seats for the passengers.

The team reserves the aircraft for the season, eliminating scheduling problems. The Dolphins go as far as reserving the same flight attendants for each flight, creating consistency for each trip.

Two NFL Teams Buy Their Own Aircraft

Two other NFL teams, the New England Patriots and Arizona Cardinals, have turned to a different option for their air travel and purchased their own aircraft. The Patriots own two Boeing 767-300s, and the Cardinals have a Boeing 777-200ER. Both teams painted their aircraft with the team colors and logos. The Patriots jets are operated by Omni Air while the Cardinals 777’s are operated by Gridiron Air.

NBA Teams Fly with Less Cargo, but Far More Often

The NBA has different air travel needs. With a much longer season and more flights than the NFL, it has fewer passengers and cargo on each trip. NBA teams use chartered flights and might fly about 300 times during the regular season and playoffs.

This affects both the type of aircraft and the operator. Most NBA teams opt for narrowbody jets like the A320 or 737, while NFL teams have gravitated towards 767, 777, A330, and 747 charters over the past few years.

NFL and NBA Team Travel Must Take Athletes’ Size and Equipment Into Consideration

The athletes are typically large, with the average NFL player weighing about 6’2″ and 245 pounds, and the average NBA player weighing 6’6″ and 215 pounds. Add to this the fact that there are about 455 NFL players who weigh 300 pounds or more and about 33 NBA players at least seven feet tall, and it becomes obvious that these athletes will not easily or comfortably fit in regular airline seats.

To ensure the athletes’ comfort, this requires different seating options than on regular commercial aircraft. The Patriots and Cardinals have only first- and business-class seats on their jets, which are larger and more comfortable than coach seats. For air travel on most teams, the standard seating arrangement is for players to have open seats next to them, giving them more room.

Player Comfort During Air Travel Linked to Better Performance in NBA

The NBA also ensures its players have enough room and are comfortable. While player comfort is nice, it is not the only concern for the teams. The league has looked at the impact of travel on player performance. The Human Exercise and Training Laboratory at Central Queensland University in Australia performed a study, “The Negative Influence of Air Travel on Health and Performance in the National Basketball Association: A Narrative Review.”

They found that NBA players spend significant time crossing time zones and flying at over 30,000 feet. The review concluded that this often results in players being tired and leads to decreased performance and more injuries. With this evidence, the NBA and other companies are now studying ways to reduce the negative impacts of travel on the players.

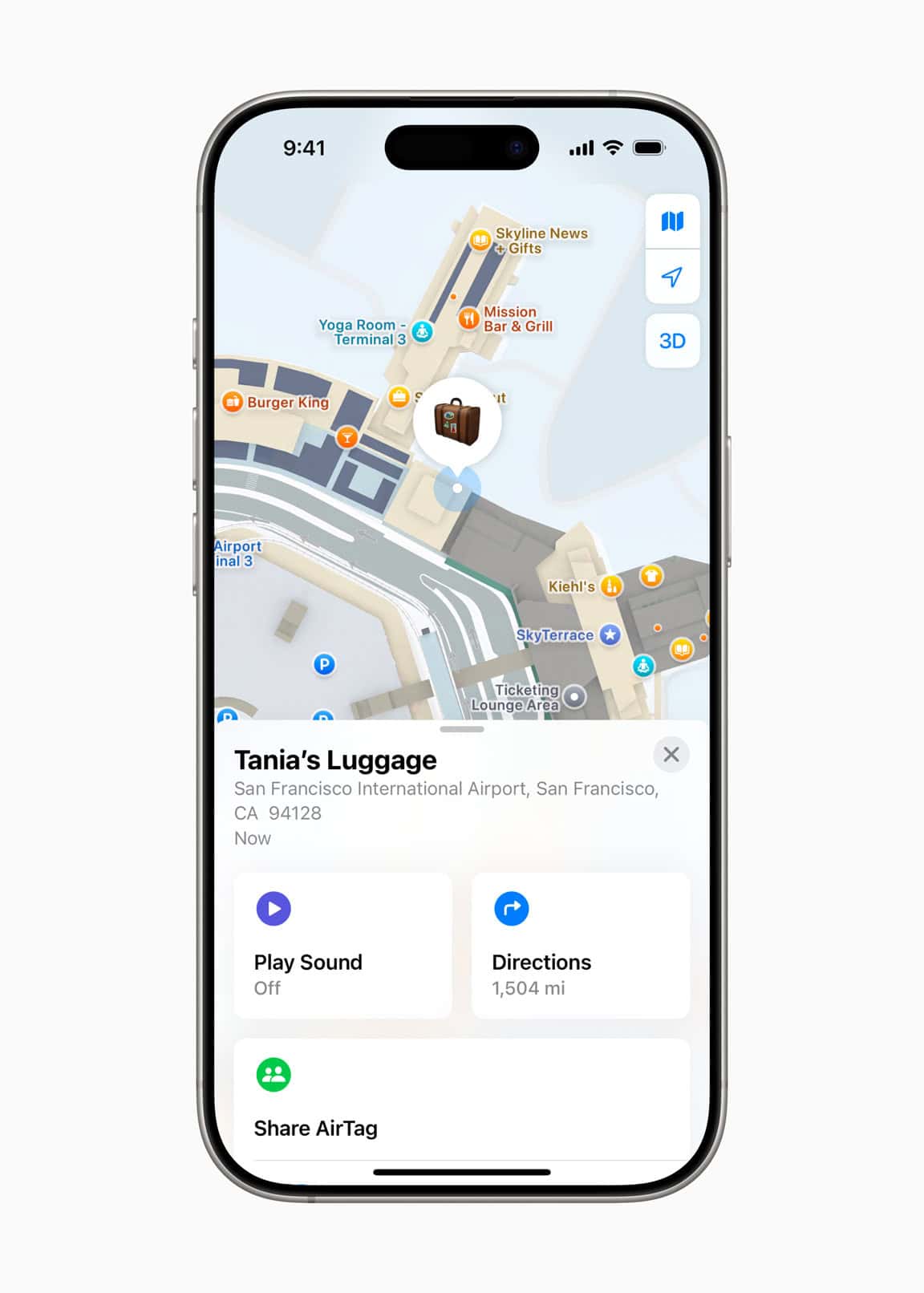

The NBA is taking a major step by leasing a fleet of 13 customized VIP Airbus A321neo aircraft for the teams. The league also plans to contract with Delta Airlines to operate the jets. Another company, Comlux, will customize the aircraft interiors with features like seats that lie flat like beds, humidifiers, lighting that Airbus claims will reduce jet lag, and pressure systems to keep the cabin altitude at less than 6,000 feet when flying at 30,000 feet.

Technology to Reduce Negative Effects of Air Travel for Athletes

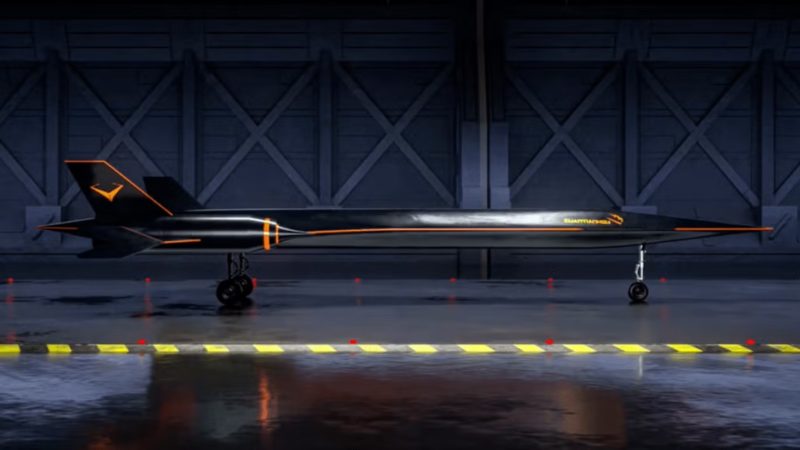

Nike and Teague are also collaborating on a project to design aircraft interiors to make travel better for athletes. They are creating the interiors to emphasize recovery, circulation, sleep, and thinking. These interiors will include advanced features like in-flight biometric systems to diagnose and treat injuries, placing ice and compression sleeves into aircraft sidewalls to promote healing, and installing organic light-emitting diode (OLED) and touchscreen monitors.

By Teague and Nike. | Image: Teague

All of this is expensive, but NFL and NBA teams are very valuable, and both leagues recognize the importance of supporting and protecting their athletes. Air travel is a significant factor for both leagues. NFL teams average about 24,000 miles of air travel per season, and NBA teams travel even more, averaging between 40,000 and 50,000 miles. Athletes in both leagues spend more time in the air than they do playing. Both leagues must find ways to ensure travel leads to better performance and more victories.