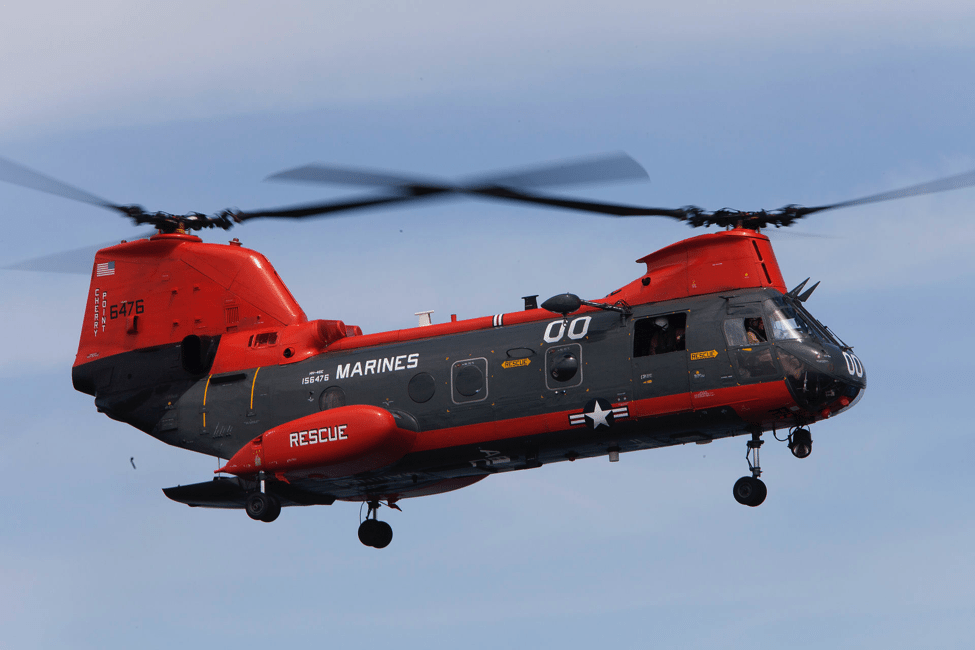

Phrog, Sea Knight…Whatever You Call It, This Trusty Helo Served Our Armed Forces for Over 50 Years.

On 22 April 1958, the prototype Vertol Model 107 flew for the first time. The 107 was a development of the Piasecki H-21 and the fifth tandem-rotor helicopter design by the engineers at Piasecki. Piasecki became Vertol in 1955. Vertol was then acquired by Boeing in 1960, and the company became Boeing Vertol.

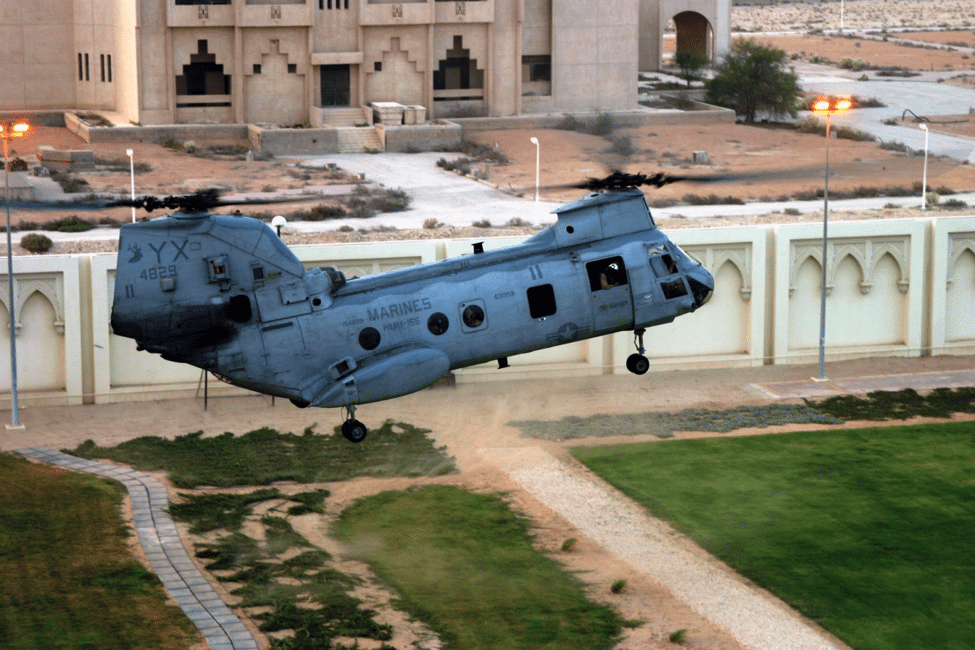

The Model 107 became the CH-46 Sea Knight. The Sea Knight, or Phrog, went on to serve with the United States Navy (USN) for 40 years and with the United States Marine Corps (USMC) for 51 years. Some still fly with the US Department of State Air Wing today.

Smiling Tandem-Rotor Workhorse

The design particulars for the CH-46 are that it was a twin-engine, tandem three-bladed folding rotor design powered by General Electric T-58 turboshaft engines. The machine mounted the engines in the tail and utilized a drive shaft to power the forward rotor. The engines were coupled in order to ensure that either could power the rotorcraft in an engine-out scenario.

The CH-46 sat nose-high on the ground, making the rear cargo ramp more accessible. Famous for their goofy-looking grinning faces and their rugged and capable character, the Phrogs worked hard to earn the respect bestowed upon them.

The Army Didn’t Buy In…at First

In June of 1958, the United States Army awarded a contract to Vertol for ten production aircraft to be designated YHC-1A. The Army then reduced the order quantity so they could spend their money on the larger but similar Model 114. Today, you know the Vertol Model 114 as the venerable CH-47 Chinook.

When the USMC decided to replace its piston-engine CH-34 Seahorse helos with a turbine-powered rotorcraft in 1960, the CH-46 was the logical answer. Even the United States Air Force (USAF) took a look at the 107, but decided to go with the Sikorsky S-61R instead, which eventually became the CH-3C and later the HH-3E Jolly Green Giant in USAF service.

The Designation Game – The CH-46 Sea Knight Gets Its Name

The designation of the production Sea Knight was changed from HRB-1 to CH-46A when the Bureau of Aeronautics changed every aircraft designation in 1962. The CH-46A first flew later that same year. Deliveries of the Marine CH-46A and the Navy UH-46A, used primarily for shipboard vertical replenishment, began in November 1964.

Both models were capable of carrying up to 17 passengers or two tons of cargo. CH-46s were used to transport personnel and all manner of cargo, evacuate wounded, supply forward arming and refueling points, perform vertical replenishment, search and rescue, recover downed aircraft and crews, and whatever other jobs required a rotorcraft with a little extra pull.

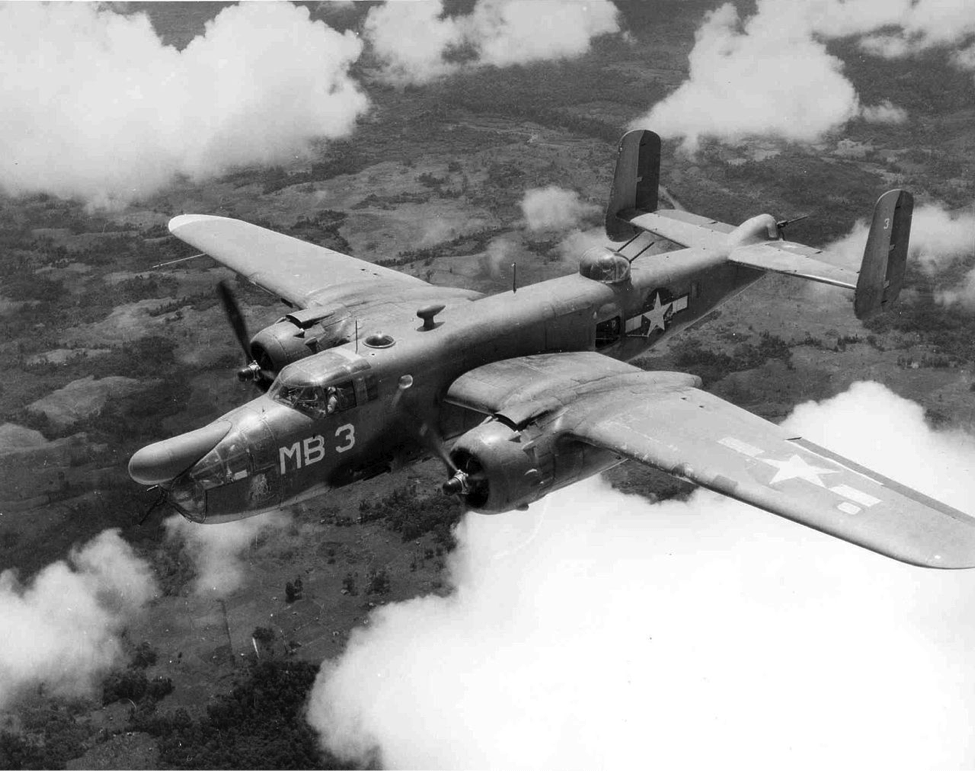

Into Combat with the Leathernecks

The first Sea Knights to see combat were Marine CH-46As of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 164 (HMM-164) Knight Riders who arrived in Southeast Asia in early 1966. The improved CH-46D became operational later in 1966. Equipped with uprated engines driving better rotors, the CH-46D could carry up to 25 troops or three and a half tons of cargo (or a ton slung underneath). The USMC took the CH-46D into combat in Vietnam beginning late in 1967. Some 34 CH-46As were reworked to bring them up to CH-46D standards. The Navy also acquired UH-46Ds to replace their A models. Sea Knight production ended in 1971 after 524 airframes had been produced.

Keeping the CH-46 Sea Knight in the Game

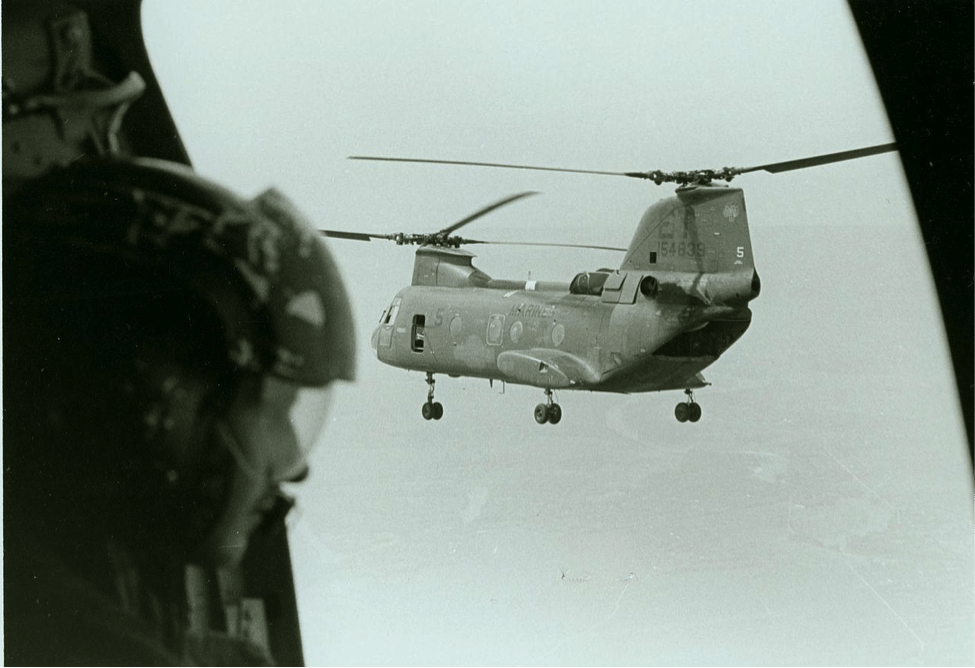

In Vietnam, the Phrog was the ultimate medium lift machine. Its capacity placed it between the smaller Bell UH-1 Iroquois and the larger Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion. Always a prime mover of troops, the CH-46 experienced peak utilization during the 1972 Easter Offensive.

CH-46s experienced their share of mechanical problems early on, though. Like all turbine helicopter engines, foreign object damage (FOD) was a constant problem that required resolution. All in-country Phrogs were grounded on 21 July 1966 until more effective intake filters were installed. The CH-46Ds were later grounded when a serious structural problem in the aft fuselage required “Iron Tail” fixes to the Phrogs under the Sigma 1 program.

Along the way, the Phrogs gained some weight by adding armor and door-mounted .50 caliber machine guns. Because of the inherent risk involved when operating rotorcraft in combat, 106 Marine Sea Knights were lost to enemy fire in Vietnam.